PHOENIX – Each day, workers at Abby Lee Farms walk down the aisles – sometimes on stilts – to inspect, prune and hand pick tomatoes on the 3-acre, indoor facility in Phoenix.

Each tomato gets physically touched by one of the 12 workers at least once, sometimes two or three times, a week, general manager Matt Sanchez said.

These employees also decide if it’s too hot or too cold for the tomatoes based on their own body temperature.

It’s that human interaction that has allowed Abby Lee Farms to provide fresh and local produce to retail stores and farmer’s markets for years.

But if given the chance, Sanchez said he would be willing to let automation do the bulk of the work for them.

“I’m for it, always finding ways to do things better,” Sanchez said. “We just haven’t had the need.”

Abby Lee has not automated simply because it’s too small.

But studies show that whether the traditional agricultural sector is ready or not, farmers are implementing automation at an exponential rate. A report by Winter Green Research predicts the global agricultural robot market will grow from $817 million in 2013 to $16.3 billion by 2020.

People have created robots to kill weeds, milk cows, move crates, pick fruits and herd cattle. Right now, a growing number of farmers and ranchers use these robots to do the kind of work most humans don’t want – or can’t – do. Some experts say technology can increase production, cost less than traditional labor in the long run and lead to higher sales.

Technological advances have made robots more sophisticated, and one study indicated that 47 percent of total U.S. employment is at high risk of becoming automated. (Photo by Erica Apodaca/Cronkite News)

But many farmers still have concerns: It is expensive to buy, it can displace workers and it sometimes lacks that human touch.

In decades prior, the agricultural sector had even been an industry protected from automation.

“(Agriculture) has been traditionally very challenging for robots and machines to work in, partly because you have these very delicate fruits and objects you have to handle, and robots aren’t really made for that,” said Heni Ben Amor, an assistant professor at Arizona State University working in the area of robotics.

Amor said that current automation is preprogrammed by a human to perform one function repeatedly. If a robot picked fruit, for example, it would grab each fruit the same way with the same amount of pressure.

Technological advances have made robots more sophisticated so they can interact with humans and adapt to their surroundings without needing additional programming.

“What we’re interested in is to introduce intelligence into these devices such that they can adapt to their environment,” Amor said.

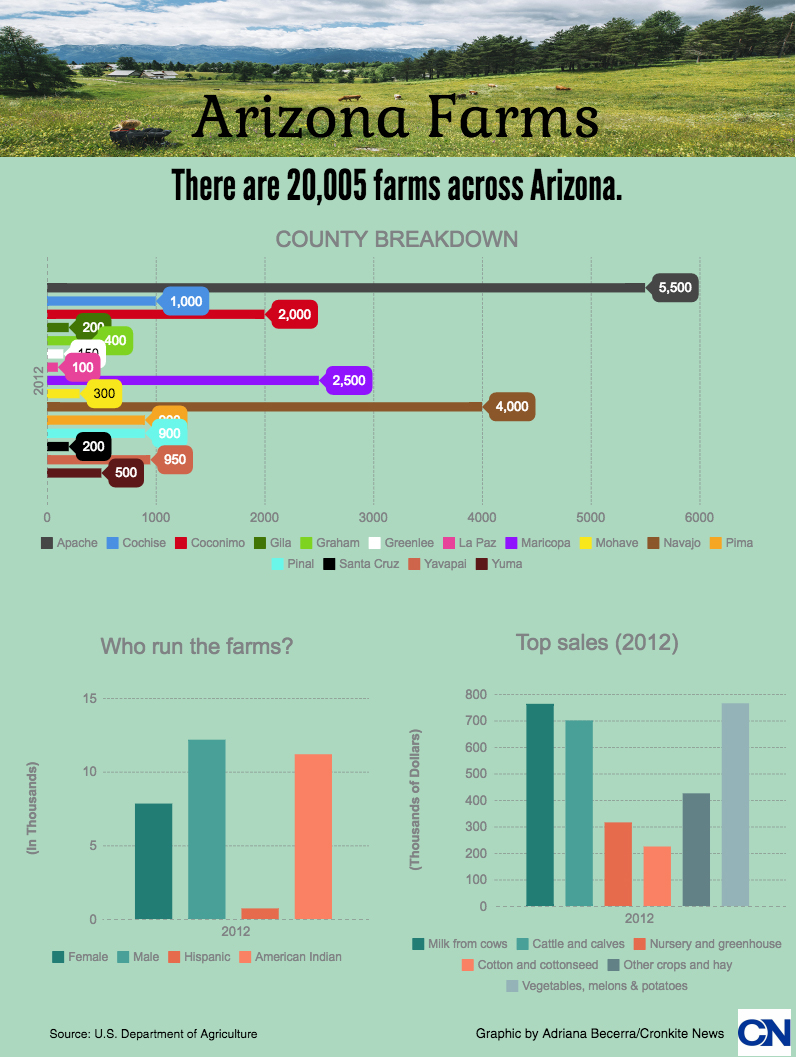

The new technology could play an important role in Arizona, where agriculture adds $7.3 billion to the state’s gross domestic product, according to a report from the University of Arizona. There are more than 20,000 farms in Arizona, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Matt Sanchez, the general manager at Abby Lee Farms in Phoenix, holds three large tomatoes grown at the facility. (Photo by Josh Orcutt/Cronkite News)

Robots can ease worker burdens

Automation can help in controlling weeds, picking produce and spraying effectively. It also can help in transporting large items, work that Andy Tolliver, head of operations at Massachusetts-based Harvest Automation, said most human workers simply can’t do.

“It is fairly physically demanding labor that not many people want to do,” Tolliver said. “People that get hired to do it, won’t come back the next day.”

This is worrisome, as farms are already seeing a shortage of workers, according to a previous article by Cronkite News.

Sanchez said the labor shortage is not just in Arizona, but across the country. He said the current administration has imposed tougher restrictions so “not many people want to do that type of work, and the people that do have a hard time getting here.”

That’s where Harvest Automation’s HV-100s come in – fully automated robots that can lift and place containers in indoor and outdoor greenhouses, hoop houses and nursery environments.

Tolliver said these robots don’t take jobs away from traditional labor.

“The robots aren’t replacing people altogether, they are taking the burden off of the people,” Tolliver said. “(People) were brought over to do a more valuable task.”

The robots can cost tens of thousands of dollars. The company started in 2007, but its robots have only been on the market for five years. They have 150 robots in the field across farms nationwide, Tolliver said.

Amor’s research focuses on robots that help humans.

“Humans can make some of the decisions, but whenever there is heavy lifting or something where you need force, the robot can then do exactly that,” Amor said.

Robots can move faster than humans, leading to higher productivity rates, which leads to higher yields and profits.

“Embracing science and technology is what is going to make us a lot more efficient,” said Wes Kerr, manager of Kerr Family Dairy in Buckeye.

Kerr, who served as young farmer chair of the Maricopa County Farmer’s Bureau in 2014, said his family remodeled their dairy farm and doubled capacity. New technology has allowed them to milk the cows more quickly and allow the cows to be “just a cow all day.”

(Video by Vanessa Herb, Hans Rodriguez and Dani Luna Mendez/New Media Innovation Lab)

Robots cost more, can displace jobs

Tolliver said it’s slow and expensive to create new technology.

“It’s not an easy thing to develop,” he said. “I think people underestimate how hard it is to get these things developed.”

A Lux Research study found that the price tag remains too high for robotics for most farms. They found that though the cost of human labor is rising, it is still cheaper than robotics because of the initial cost.

Despite some claims that robotics are more efficient than humans, this study noted that automation didn’t reduce workloads and chemical costs or improve yields.

This is especially true for smaller farms like Abby Lee, where the production is too small to truly realize productivity gains from automation.

Daniel Bliss, an associate professor at Arizona State University’s engineering school, said he believes technology will force a “mass retraining of skills” as automation becomes more prevalent. (Photo by Megan Bridgeman/Cronkite News)

In general, ASU professor Daniel Bliss said he believes technology will force a “mass retraining of skills” as automation becomes more prevalent.

“What we see now is the rate of disruption is increasing and the timescale of this disruption is going to make it harder and harder for people to keep up,” said Bliss, the director of Bliss Laboratory for Information, Signals and Systems.

Robots, like the one created by Harvest Automation, might complete tasks so that farm workers can focus on other aspects, but this could require them to learn new skills.

In a 2013 study about the future of employment, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne examined 702 occupations and indicated that 47 percent of total U.S. employment is at high risk of becoming automated.

Bliss also said it is possible for larger companies to crowd out smaller companies because they have the resources to get new technologies first.

“There are winners and losers,” Bliss said. “On the upside is that overall economic efficiency goes up and the downside is you have people who are displaced.”

What the future holds

A student at Heni Ben Amor’s lab at Arizona State University demonstrates a robot’s capabilities. It took them four years to create the robot, and it took the robot 1 ½ hours to learn how to pick up the cube. (Video by Adriana Becerra/Cronkite News)

Bliss said many people, including politicians, tend to think jobs are being lost from trade or outsourcing, but technology is the main culprit.

“So when we tell somebody that we are going to bring those jobs back, we might be able to bring some of those jobs back, but the underlying forces are to make many of those jobs go away,” Bliss said.

Amor said that as automation becomes more commonplace, lawmakers need to enact legislation draw clear lines between robots and humans. For example, if an autonomous car got into an accident, who would be at fault? The person behind the wheel or the car manufacturer?

As society wrestles with both the ethics and the legalities of automation, developers will continue to move forward.

“As the bar is being raised at to what technology can do … we’re always going to be pushing for the next big thing,” Tolliver said.

Amor’s robotics lab is even experimenting with robots that can recognize and apply the right amount of pressure, which could eventually be used in agriculture to pick sensitive fruits and vegetables.

In addition, Amor hopes the interactions with robots will become easier.

“Instead having a programmer program the robot, you could just walk up to the robot and say ‘hey that was wrong, could you please do it this way’,” Amor said.

As technologies continue to become more widespread, the costs will likely decrease, making it more affordable for companies to implement.

“The wealthy, bigger farms are actually deferring most of the cost,” Kerr said. “They’re taking the first technology, which is expensive, and taking the kinks out of it.”

Overall, Kerr said most farmers are “savvy” as to what technologies will help them stay in business.

“The pressure to stay profitable is so strong because prices fluctuate so much from year to year so it really is trying to stay in business,” Kerr said. “The market kind of weeds out of the folks that can’t really adapt.”