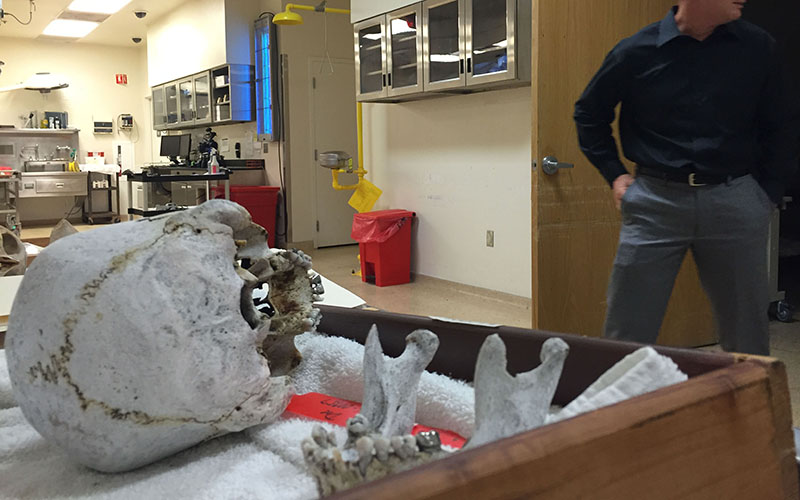

A photo from September 2016 shows the ID tag of human remains at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner. (Photo by Lily Altavena/Cronkite News)

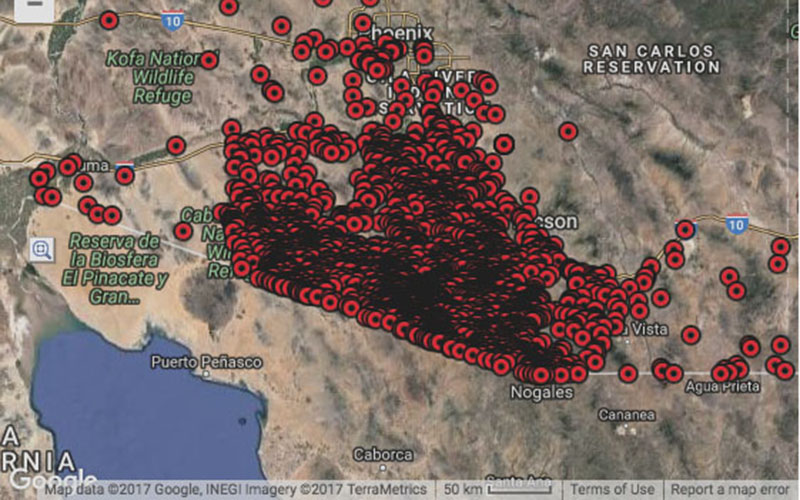

PHOENIX – It might take a second to for the computer to load, but then it’s there: a map of Southern Arizona nearly completely covered with red markers, so dense in some areas that it’s black.

Each marker indicates one migrant who died trying to cross the U.S./Mexico border into Arizona.

The Arizona OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants started in 2001 and is managed by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner and Humane Borders, Inc. One of the groups’ goals is for anyone to be able to search for documented dead migrants based on what they know about them – their name, gender, year of death, the county in which they died, etc.

But if you leave the criteria blank and click search, the map will show every migrant whose death has been documented over the past 16 years. There is a total of 2,797 markers on the map as of the writing of this story.

“We’re not even looking for these people,” said Humane Borders Executive Director Juanita Molina. “We’re just finding them.”

The causes of death are listed in the results if they are known. Hyperthermia, heat stroke, and exposure to the elements are common listings. And the map serves a dual purpose for both organizations involved in developing it.

A photo from September 2016 shows human remains at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner. Dr. Gregory Hess said many of the remains belong to migrants who crossed the southern border. (Photo by Lily Altavena/Cronkite News)

For Humane Borders, the map shows high-traffic areas where representatives can leave jugs of water for those crossing. Molina said it’s “physically impossible to carry enough water” for a safe journey through the Tucson corridor.

And for the Office of the Medical Examiner, the map helps officials piece together the remains of a single migrant, many of which the office discovers at different times because they are scattered by weather or animals.

Dr. Gregory Hess, chief medical examiner for Pima County, said each marker on the map represents the earliest remains of a person were found to more closely approximate when they died. Hess’ office examines all the remains, determines the cause and manner of death, and returns the remains to families, he said.

He also updates Humane Borders monthly with a list of new remains that have been found.

Gary Christopherson, a Humane Borders board member who oversees the map programming, said the remains are found by law enforcement officers, border patrol agents, and people hiking. He said there are groups that go out to look for bodies, though that isn’t something Humane Borders does.

He said it’s difficult to determine when the person died based on their remains.

“If there is still flesh on the bones, the medical examiner can give an approximate date of death,” Christopherson said. “If it’s just skeletal remains, it’s difficult to do that.”

He said John Chamblee, a Humane Borders research director who wasn’t available for comment, started and designed the map and secured funding for it over the years. He said other states are trying to do similar things with mapping, but he wishes there could be a coordinated mapping effort across the border.

He said the mapping involves “a lot of money and a certain persistence.” Because of that, it’s difficult to make that a priority in other counties, he said.

Christopherson said one of the reasons the map began was so families could try and track down their missing loved ones, which is easier to do when the remains are able to be identified. Out of 2,731 total remains found as of January of this year, Christopherson said 947 remains were unidentified.

A screenshot of the Arizona OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants shows all the migrant deaths Pima County and Humane Borders, Inc. have tracked over the past 16 years. (Screenshot from Humane Borders website)

Molina said migration has been down on all counts in general, but she refutes the notion that this is related to the election of Donald Trump. She said Former U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson took many measures to “stop migration before it reached the United States,” and that we’re now seeing the effects of his actions.

She said the number of people crossing fluctuates often, particularly with the changing seasons. But there are other trends have been documented since the map project began.

She said after 9/11, law enforcement officers focused on securing urban and popular areas first. A stronger law enforcement presence in urban areas caused migrant routes to shift to less populated – and often more dangerous – areas, she said. Arizona was “especially dangerous” in this situation, she said because much of the wilderness includes places with no water, food or cell phone signals. She said the map has shown that “people are dying further from towns and roads.”

The whole project began after 100 remains were found in a single year in the early 2000s. Molina said the question of intervention was raised among Humane Borders and other faith and humanitarian groups wanting to do something about it.

Despite the toll it takes on those documenting the dead, Molina said she feels comfort in “being able to be of service in some way in this midst of this horrible crisis.”

“It’s a spiritual practice to witness such horrors,” Molina said. “We’re looking at a rate of death that is devastating to our community.”

When Molina thinks about each red marker on the map representing a human being, she said she contemplates the “generational footprint” this leaves on all these people and their families.

“Some will have resolutions,” she said. “But thousands more won’t.”