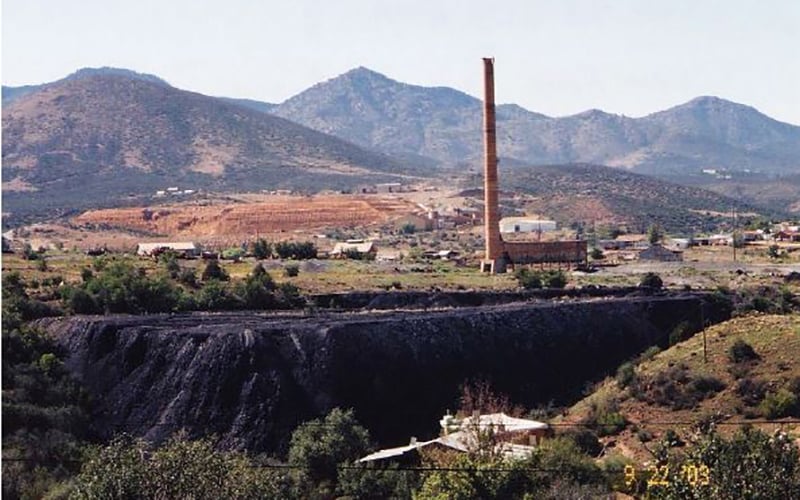

WASHINGTON – In the nine years since the former smelter near her house in Dewey-Humboldt was added to the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of toxic Superfund sites, Rose Eitemiller said she’s seen some progress. But not much.

The EPA removed surface soil from the Iron King Mine-Humboldt Smelter site, which is laced with arsenic, and replaced it with clean soil on her property and others in the area, but “two feet below … is still contaminated,” Eitemiller said.

“The holdup for cleanup is federal money,” she said of the pace of progress.

Advocates say the pace is not likely to pick up at Iron King or any of the 1,336 other Superfund sites in the U.S. after the Trump administration outlined a fiscal 2018 budget that proposed cutting the $1 billion cleanup fund by a third, or $330 million.

Administration officials say the cuts are intended to rein in administrative costs on a program that even supporters concede is not working, and to direct more responsibility and control over cleanups to state, local and tribal programs.

But critics say the move will cripple an already struggling initiative to clean up toxic sites, including Iron King and eight others in Arizona. Not only will it stall forward progress, they say it will lead to backsliding.

“Basically, what you are going to see is no clean up,” said Roger Featherstone, director of the Arizona Mining Reform Coalition.

“In some bizarre notion of state’s rights, the Trump administration’s philosophy is that they can defund everything and let the states handle it,” Featherstone said. “Of course, the states are in no financial position to do that.”

“Superfund” is the common name for the National Priorities List, created by the EPA in December 1980 to identify and clean up the most toxic sites in the country. The EPA forces those responsible for contamination to pay for cleanup – when it can. Often, as in the case of Irong King smelter, a polluter cannot be identified or is no longer around to pay the bills, which is when the federal government steps in.

Arizona has nine sites on the list, six of which have been on the list since the 1980s.

-Graphic by Joseph Guzman

Environmentalists say sites like those in Arizona have stayed on the national priorities list for decades due to the lack of resources in federal budgets and a government that has been lax on cracking down on polluters.

“We’re going to have more of this problem not less. More and more people will be poisoned and kids will have toxic water and play on toxic land,” said Bradley Angel, director of the group Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice.

Angel said President Donald Trump’s proposed cut to the program will harm the most vulnerable communities threatened by contamination.

“This is not a tree-hugger issue; this is an issue of life and death for Americans,” Angel said.

But critics of the Superfund program welcomed the cuts, saying it was a reasonable portion of the budget to cut and that continuing to fund the program is throwing good money after bad.

“After this point in time, it (Superfund) probably has cleaned the dirtiest sites by now that pose the greatest threat,” said Jim Tozzi, the head of the Center for Regulatory Effectiveness.

Tozzi, who was around when the Superfund program was created, questioned the efficiency of the program saying the amount of time it has taken the EPA to complete cleanup of sites on the list makes budget cuts justifiable.

“The Superfund program has been around for 20 to 30 years, when will it mature?” he asked. “Sometimes things have to end – we’re $20 trillion in debt, we’re mortgaging our kid’s futures.”

But Featherstone called that short-sighted thinking by the Trump administration that would inevitably cost more money, more lives and further damage.

In the meantime, Eitemiller and her neighbors continue to wait for action at the Iron King Mine-Humboldt Smelter.

“The smelter is where they did all the processing,” Eitemiller said of the site that was added to the Superfund list in 2008. “It was a railroad that they actually turned into a street, which is my street.

“There was a lot of spillage of arsenic and lead and beryllium, so we were just highly contaminated,” she said.

When the EPA came and tested, it found high levels of arsenic. But it has not removed more than the topsoil

“All they’re (EPA) worried about is the contamination that can be touched and is exposed,” she said. “There are those who actually have cancers due to contaminants, most of them you’ll find it’s due to arsenic in the well water.”

She says there is still work to do. But concedes that even those living in the shadow of the smelter disagree on the impact the contamination has actually had on their daily lives.

“There will be those that are like Chicken Little,” Eitemiller said, “and then there’s those who say they have lived here 47 years and it hasn’t affected them.”