ALMEACO DE BONFIL, Mexico – For the family of Sofia Aristeo Serdan, financial success is measured in small steps.

It’s taken over a decade for the family of eight to move up from being a part of a bleak statistic. With the help of a government program, they’ve gone from being classified as living in extreme poverty to being simply impoverished.

It means no longer earning less than $3 U.S. a day; they now make about three times that.

Since 1997, a government-run social program, originally known as Progresa and currently known as Prospera, has tried to tackle poverty in a country where more than half of its 130 million residents are poor.

Prospera uses an incentive-based approach: In exchange for agreeing to better health, nutritional and educational practices, the program’s beneficiaries receive money from the government every two months.

In the two decades since the program was implemented, that incentive-based approach has been used as a model by anti-poverty organizations in 62 countries, according to Fernando Castillo Diaz, head program coordinator for Prospera’s Queretaro office. Prospera’s website notes that more than 12 million people in 28 Mexican states have benefited from the program.

But critics question the program’s efficiency in eradicating poverty for the long term. They say that too little money is spread among too many people.

“The thing is that the program has a little budget, but it tries to help everyone,” said Giovanna Galicia, who works at a Queretaro nonprofit, Descubriendo un Amigo. “People in the worst conditions cannot even live with that and not even eat with that.”

But the help has benefited the Aristeo family, not only financially, but in the way it approaches life, said the family matriarch.

Sofia Aristeo Serdan, 40, stands on the front lawn of her two-bedroom house nestled in the rural area of Almeaco de Bonfil, about 60 miles outside of Santiago de Querétaro. (Photo by Danielle Quijada/Cronkite Borderlands Initiative)

For years, Aristeo sought to escape a life of menial jobs and limited future, not only for herself but for her children. She said she believed her primary purpose in life was to obey her husband and raise their children.

As she sits on the front lawn of her two-bedroom house, Aristeo said she now has larger dreams, especially since her six children have prospects for promising futures.

She didn’t have the same opportunities. She said she was raised to believe that her life would consist of making less than a few U.S. dollars a day, having as many kids as “God blesses you with,” and prioritizing duties at home over education.

Now 40, Aristeo said she began working in the fields at age 6 and often only attended school two days a week.

She greatly enjoyed school, but Aristeo said she had to forgo full-time attendance so that she and her siblings could help put food on the table for her family.

“It was hard when I told my father that I was about to graduate from elementary school and that I wanted to go into middle school,” she said. “All he said was, ‘No,’ that women were not born to study, that we had to dedicate ourselves to taking care of a man, in the good and bad, whether they treated you good or bad, you always had to be submissive.”

She said that her father was both alcoholic and abusive, which made it even harder for Aristeo to pursue a life outside of poverty.

“But I had that long-term idea of being able to keep going,” Aristeo said. “I saw my mother suffer through that, and believe me, I said, ‘No, not me! Even if my father says it, I’m not going to do it.'”

Aristeo never did get to continue her education. At a very young age, she began her life as a wife and mother just as she was expected to do.

However, Aristeo and her husband, Antonio Salvador Camaigo, decided to change the course of their lives 18 years ago when their first child was about 7 years old.

“We got to that moment when we both said, our parents can’t tell us what to do anymore,” Aristeo said. “We take responsibility for having a large family, and now we have to be responsible to seeing that they succeed.”

The couple decided to participate in Prospera.

More than 92,000 people in Queretaro state participate in the Prospera program, through which they receive periodic conditional cash transfers (CCTs) for participating in better health, nutrition and education practices for their families.

The program has undergone several changes and reforms to improve its effectiveness since its 1997 inception.

Initially, the program provided the basic essentials of education, nutrition and health for families in need. However, Prospera’s website says the program has expanded to helping beneficiaries gain social security, housing and higher education, as well as job and financial training.

Castillo, Prospera’s Queretaro program coordinator, said the most recent program revisions took place shortly after President Enrique Peña Nieto took office in 2012. Castillo said the new administration set out to make Prospera more strategic for families, with new components like scholarships for secondary school and projects that promote self-sufficiency.

Castillo said that, depending on the government budget, Prospera staffers periodically go into poverty-stricken areas to seek out new beneficiaries, people who earn less than $3 a day and thus could be eligible to receive conditional cash transfers every two months.

In order to receive payment, Castillo said the participants must be proactive in improving their health, nutrition and education practices. This includes attending doctor appointments, informational events on family health and making sure their children attend school.

Pablo Ibarraran, the Inter-American Development Bank’s Mexico City-based social-sector specialist, said the incentive-based program has influenced other countries to initiate similar programs that try to “provide the same type of services to the lower class that they do to the middle class.”

Pages full of names sit on the tables outside of the Querétaro Prospera Program site on Friday morning on March 3, 2017. (Photo by Danielle Quijada/Cronkite Borderlands Initiative)

Ibarraran said that CCT programs are the best tool governments have yet to tackle extreme poverty.

He said such programs focus on who needs the most help and then gives financial incentives to prod the families into making positive lifestyle changes.

The Prospera program distributes the CCTs to the female head of house to ensure that the money is used toward health, nutrition or education, he added.

“It’s all very transparent and there is not distribution distortion,” Ibarraran said.

Equally important, Ibarraran said, is the investment in human capital. The program’s requirement for parents to ensure their children are actively pursuing education and maintaining good health is an example of this focus on people, he said.

“Families are responsible to invest in human capital and the state (or government) is responsible to provide the resources and services,” Ibarraran said.

He added that since the social program’s implementation, families are now “well aware that they have rights and they can demand those rights, like the rights to education and health.”

David Androff, an Arizona State University School of Social Work professor, said that programs that invest in children are usually more effective over the long term.

“CCTs give help for poor people, for people below a poverty line, but rather than just giving money, it’s a way to work with poor families. When you start with younger generations, anti-poverty programs can have a bigger impact,” Androff said.

A criticism of an incentive-based program like Prospera, Androff said, is “many people say it’s a form of control – a type of behavioral control, a social control.” Critics, he added, “say that the main part of the program is that it is supposed to help people and that they (recipients) should just be eligible for money.”

Nora Elena Hernandez, the founder and president of Descubriendo un Amigo, the Queretaro nonprofit, said that while the government program provides services and help for some, it is not nearly enough to make a dent in the country’s need.

Hernandez explained that since the program’s implementation, the government has tried to help millions of families but has fallen short. She added that because services are stretched thin, the program leaves gaps for nonprofits like hers to fill.

Hernandez said that while beneficiaries have better access to life’s daily essentials, many are left without the necessary skills and knowledge to advance out of poverty.

A report from the World Bank showed that 53.2 percent of Mexico’s residents lived in poverty in 2014, a 4 percentage point increase from 2008.

Castillo, from the Queretaro Prospera program, said that although there is still a high rate of poverty within Mexico, the extreme poverty headcount has decreased. He added that more than 65,000 kids from the Prospera program are currently enrolled in colleges in Mexico, giving them a higher chance of breaking the poverty cycle.

He said that for most families, it takes three to four year to show signs of self-sufficiency.

However, for Aristeo’s family, it took twice that long.

Various kitchen utensils sit on the cluttered table and stone wall of the Sofia Aristeo Serdan’s family house. Help and guidance from the Prospera program has allowed the family to slowly emerge from extreme poverty. (Photo by Danielle Quijada/Cronkite Borderlands Initiative)

They live in a two-bedroom house surrounded by acres of lush, green land in the middle of Almealco de Bonfil, a city of 50,000 about 37 miles outside of the state capital of Santiago De Queretaro.

At the family’s home, dozens of goats murmured in the background in between the coos and the clucks of chickens. They use products from their livestock – meat, eggs, fur – as part of a sustainability project that includes composting and organic crops to earn more than 3 times what they used to earn. Now they earn about $60 a week from the project, she said.

But the move to entrepreneurship, didn’t come easily.

“When I received Prospera, I still had no motivation to do anything else,” Aristeo said. “We depended solely on my husband’s income.”

She said a visit with another government agency in 2007 helped her realize that she could help improve her family’s life.

“I felt powerless not being able to help my husband give our children something better,” Aristeo said. “Even more so because when we were kids, we didn’t have an opportunity like that, and truthfully, we didn’t want our children to have the same problem.”

The newfound motivation led to her sustainability project using their livestock and their land. Their project has received statewide recognition, she said.

“It’s (the project) the one that awakened me, it ripped me from the mundane life I had before,” Aristeo said.

The success has inspired her to try to fulfill another dream.

Sofia Aristeo Serdan crouches down to tend her plants. Each of the different plants and natural resources on the Serdan property help the family with their sustainability project that they started about 10 years ago with the help of Prospera. (Photo by Danielle Quijada/Cronkite Borderlands Initiative)

At about 10 a.m. every Wednesday, Aristeo attends class where she is pursuing the middle school education that she wasn’t able to finish as a child.

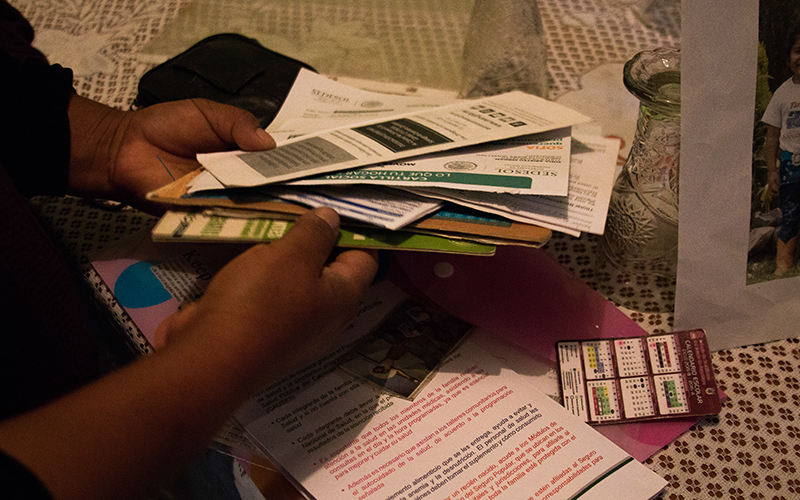

She credits Prospera for giving her family a better life.

“When we were told that Prospera not only gave nutritional assistance, but that our kids could receive a scholarship to continue their studies, for me it was great because I knew my kids would be able to achieve so much more than I had been able to.”

Aristeo’s two oldest children are currently pursuing secondary education in sustainability to further establish their at-home business.

Her younger children are still in primary school, but are making strides and are at the top of their class, Aristeo said.

While it is hard to predict exactly where her children’s lives will lead, Aristeo said that she has hope for the future that they will be able to finally break the cycle of poverty for good.

“I try to do the best I can for them, so that they can do the best for themselves.” Aristeo said.