PHOENIX – Imagine a road trip in 2030 on a super interstate highway that stretches from Arizona’s border with Mexico to the U.S.-Canada border in Montana. And it won’t be just a road on which you drive your car, but an economic investment to the communities through which is passes.

Ian Dowdy, director of the Sun Corridor program, said the institute wanted to put the time to research, develop, and team up with other groups to make the proposed transcontinental highway, CANAMEX, something that will not be outdated by the time it’s built.

“It’s a really important project and I don’t think people will appreciate it in the way that they should,” Dowdy said.

In 2012 Congress approved a transportation omnibus bill, MAP-21. It was intended to provide direction on transportation funding. MAP-21 provided funding for the planning and study of possible corridor routes for I-11, according to the Sonoran Institute’s website. However, it didn’t provide funding for the highway itself.

(Map by Caity Hemmerle/Cronkite News)

Sonoran Institute’s role

The mission of the Sonoran Institute is to connect communities to the natural resources that nourish and sustain them. Dowdy said the Sonoran Institute became involved with the CANAMEX project four years ago.

“In reality, we are in a role as an organization to give communities the tools that they need to make better decisions,” Dowdy said. “We think that people in communities want to preserve their natural landscapes and that they want a high quality of life and a strong economy. We want to accomplish all three of those things.”

He said in most situations communities are given a false narrative that they have to choose between a good economy and a good environment.

“We know that’s not a real choice,” Dowdy said. “People can actually have both. So we try to help communities make those decisions where they can achieve their ambitions and many of their ambitions.”

He said the project provided an opportunity to both combat the concerns that people have about climate change and would provide an excellent domestic source of energy.

He said there would be economic development in Arizona with the ability to expand the renewable energy economy.

Three universities get involved

Dowdy said who better to plan the future models than the future? Students from Arizona State University, the University of Arizona and the University of Nevada-Las Vegas became involved and were divided into studios at their universities to design the I-11 corridor of the overall CANAMEX highway.

In the spring of 2014, the three universities embarked on a multidisciplinary “design studio.” Students in landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, and other disciplines collaborated to envision designs for different segments of I-11.

Linda Samuels, then director of the Sustainable City Project at UA and now Associate Professor of Urban Design at Washington University, was one of the leaders of the project. She said the standing challenge was to encourage students to really leverage their knowledge into something that could both be socially and environmentally productive.

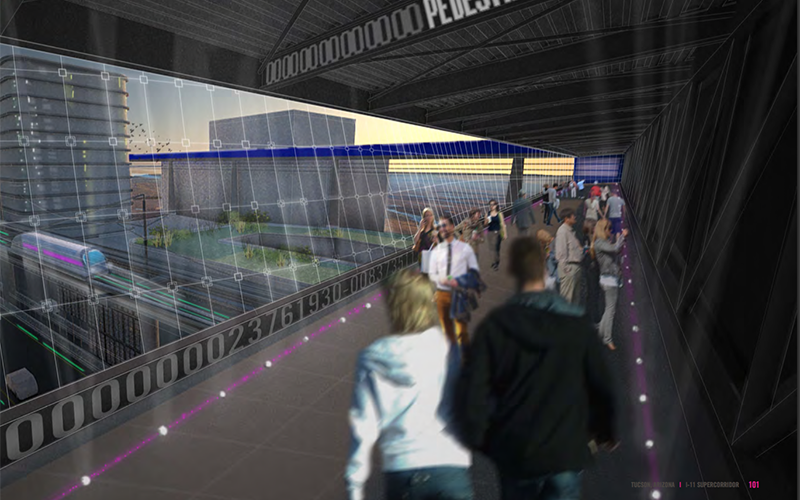

Rendering of a pedestrian overpass for the proposed CANAMEX highway. (Rendering by Bernardo Terán. Energy City Team: Steven Giang, Sally Harris, Kendra Hyson, Katie Laughlin, Bernardo Terán; faculty advisors: Linda Samuels, Arlie Akins, Mark Frederickson)

“I was a participant in the Walton Sustainable Solutions Initiative ‘sandpit’ and our team emerged from this process,” Samuels said. “We competed for a large grant to support implementation, but did not win the event.”

Regardless, she said, they chose to work together and plan a three-school, three-city collaboration. The University of Arizona studio, run by Samuels in conjunction with Arlie Adkins (urban planning) and Mark Frederickson (landscape architecture), collaborated with planning, architecture, and landscape architecture students throughout the semester and over the summer.

The studio was based on reimagining I-11 as next generation rather than last generation infrastructure (see Figure 1). The project extended for an entire year culminating in multiple presentations to project stakeholders and relevant professionals.

Both the Arizona Departments of Transportation (ADOT) and the Sonoran Institute were partners from the beginning. UA’s Renewable Energy Network and Walton Sustainable Solutions Initiative both funded its efforts in the end.

The work that Samuels and other groups have done has pushed ADOT to broaden its impact assessment to include a wider range of social and environmental issues.

“Our objective is to have both short-term impacts on decisions around I-11 – if you can call a huge road short term – and longer-term impacts on the way states and other agencies consider infrastructure,” Samuels said.

Jason Boyer, a former lecturer at ASU, structured the studio in Tempe. ASU offered the studio to about 15 fourth-year architecture students. (UA had 39 students from all three disciplines).

UNLV offered its studio to about 12 to 15 students. The focus of the three studios was on the I-11 from Nevada to the Mexico border. At multiple points throughout the semester, they would meet up at their universities to collaborate.

ASU students were divided into five teams and responsible for designing portions of the highway. Boyer said they drove and studied these locations in depth for further design. Areas included the zone through Casa Grande, Metro Phoenix, and the area between the Nevada border and Phoenix.

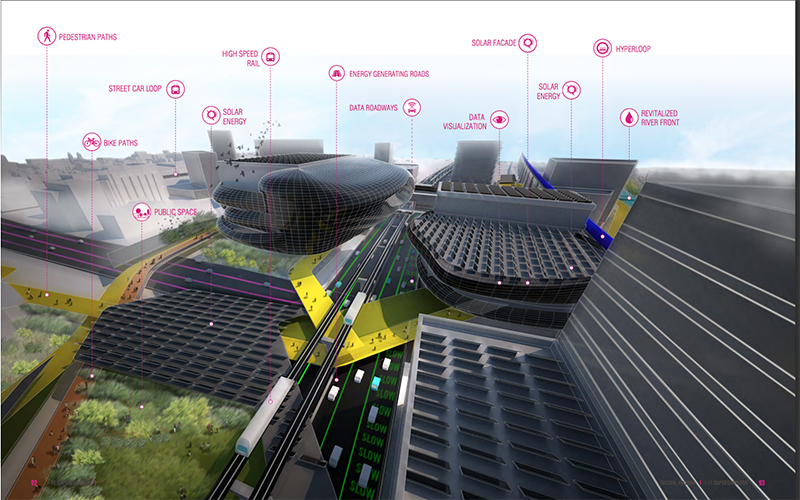

“They were looking at the feasibility for how we could rethink the design of our infrastructure,” Boyer said. “The CANAMEX corridor is a highway but next to the highway is typically a rail line, power, security data, a whole set of infrastructure runs next to highways.

“So we started to think about how we could sort of rethink what transportation infrastructure is and could be to aggregate a whole set of infrastructures together that might include some aspects of sustainability such as solar, algae and water resources,” he said.

A rendering showing the various sustainable elements as the proposed I-11 passes through Tucson. (Rendering by Bernardo Terán. Energy City Team: Steven Giang, Sally Harris, Kendra Hyson, Katie Laughlin, Bernardo Terán; faculty advisors: Linda Samuels, Arlie Akins, Mark Frederickson)

Looking down the road

Boyer said the sheer scale was the hardest part of the project. He also said that UA had an advantage of having a mixed class of architecture planning, landscape architecture and had a cross-pollination of background. In turn, it was difficult for the ASU students to understand how to break down the scale of the space that they were focused on.

“They were used to working on project-specific sites including a building solution and this was more about urban infrastructure that could tap into existing building assets or spawn economic development and future buildings,” Boyer said.

He said the project is vital to the economic security and development of the Southwest. He said Arizona needs to make sure it’s a part of the process.

“Places like Texas, California, and Nevada will find a different route that will bypass Arizona and Arizona runs the risk of becoming irrelevant from a transportation infrastructure planning standpoint,” Boyer said.