A human bone found in the desert in Ajo. Taylor James photographs items he finds along migrant trails in southern Arizona. (Photo courtesy of Taylor James)

PHOENIX – Amid the marches, political organizing and other demonstrations that have taken place among those in opposition to President Donald Trump, Phoenix’s Latino arts scene has seen direct and indirect messages conveyed across a variety of media pushing back against Trump’s policies and public statements.

From protest signs and political satire to more biographical work that highlights the stories of immigrant communities, these artists are making their voices heard and their messages prominent with a renewed focus on themes of unity and acceptance under a president they say has fostered division and intolerance.

Casandra Hernandez, curator of CALA Alliance (Celebración Artística de las Américas) at the Arizona State University Art Museum, said trends have included Latino artists affirming the stories and experiences of immigrants and focusing on the deep history of immigration and transborder life.

She said that while so much political rhetoric aims to create fear and division, it is an act of resistance to create spaces of connection, dialogue, and understanding.

“I feel like many artists … are also looking at affirming the presence of immigrants, the presence of Latinos, the contributions of our communities,” she said. “Our nation’s history is incomprehensible without understanding immigrants’ contributions.”

The satirist

James Garcia, founder of the New Carpa Theater Company, is preparing a satirical play surrounding the effects of SB1070 in Arizona. (Photo courtesy of James Garcia)

James Garcia, founder of the New Carpa Theater Company, is preparing to premiere a play that he said has been a long time coming. It’s about a family in Phoenix facing the effects of SB1070, Arizona’s controversial immigration bill passed in 2010 that was partially undone by the U.S. Supreme Court. Garcia said that while the play itself is about events in 2010, the message of the play is connected to current conversations about immigration.

“I really feel like I have something to say,” he said. “Some commentary that I’m infusing into the work.”

Garcia, who founded the theater company 11 years ago, has been writing and managing a variety of dramas, satirical works, and pastorelas – traditional works of theater in Latin American countries centering around bible stories of the nativity scene that were used by Spanish conquistadores in converting the native communities in the Americas to Catholicism.

But Garcia said his pastorelas put a contemporary and comedic twist on these performances. While traditional pastorelas focus specifically on the Bible story of shepherds following the star of Bethlehem to reach the baby Jesus, Garcia’s most recent pastorela that ran during the Presidential election centered around a family in northern Mexico who got amnesty under President Ronald Reagan and makes a journey to Phoenix to re-register to vote once they hear Trump is running for president.

He said it’s important that with his upcoming play, the views of people who were affected by SB 1070 are known to the public.

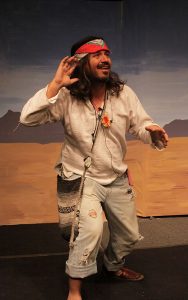

Masavi Perea acts in one of James Garcia’s previous pastorela performances. (Photo courtesy of James Garcia)

“Legislation like SB1070 and what Trump is doing now is unnecessarily hostile to immigrants in America in a way that to me is contrary to democratic values and is destructive to the economy in the long run,” he said.

He said the fact that New Carpa is small and has a lower budget than most local theaters allow the company to produce shows they wouldn’t get to see elsewhere. When he wrote a play about the DREAM Act and DREAMers, he said he distinctly remembers one young woman walking out of the theater talking to her friend and telling her “that’s my story.” He said it’s important for people to see themselves reflected in the characters onstage.

“1070 is something nobody else would be taking on,” Garcia said. “Most theater companies are much more conscious about making money staging plays, selling enough tickets.”

Garcia said he’s not trying to appeal to an audience that thinks like him or trying to shun those who disagree with him politically. He said he wants audiences to understand what’s happening to people around them, and make people feel less alone.

“I don’t try to oversell the fact that if I write a play about SB 1070 or American pastorela, that it’s going to change the world,” he said. “But I feel confident that I am contributing a voice to the collective voice that is pushing back against that kind of reactionary and intolerant mentality.”

The photographer

While James Garcia sets out to create his art with a specific message in mind, photographer Taylor James lets his environment guide his work.

James, a graduate student at ASU, took a class two years ago that involved going out into southern Arizona and leaving water at strategic locations for migrants crossing the border into the U.S. on-foot. He said he wanted his work to show people what the experiences of these migrants are like.

A can of pinto beans that was part of a humanitarian food drop for migrants crossing the desert in southern Arizona on foot was vandalized. (Photo courtesy of Taylor James)

James uses an interactive mapping program created by Pima County and Humane Borders, nonprofit supporting migrants who cross on-foot through the desert, to plan where he will go to shoot his photos. The maps pinpoint the locations where migrant deaths have occurred. James then goes out and photographs various objects — clothing, toys, even human remains — that he finds.

“If you can ignore the nonsense on the news and the nonsense from the president, the human element is someone risked their life to cross the desert and it cost them their life,” he said. “If you can grasp that need for survival, my hope would be that you can see past the politics of it all.”

He said most of the reaction he’s received from his work has been positive and has sparked discussion among viewers over the laws and risks associated with migrant crossings. James said art is meant to be a mode of discourse in this way, and that for him, photography and art are ways to “transcend or translate different things.”

“It almost becomes me kind of listening to the work,” he said. “In a way, I’m trying to make sense of the world through my art or through image making”

The sculptor

Margarita Cabrera said the word “resistance” in regards to art makes it seem like the work is causing a standoff. She prefers to think of her art as a platform for members of various diverse communities to come together and see each other in new ways.

Artist Margarita Cabrera brings together members of immigrant communities to cut up U.S. Border Patrol officer uniforms and restitch them into life-size sculptures of cacti and other desert plants. (Photo courtesy of Margarita Cabrera)

“Sometimes, there’s a need to stand up and be aggressive in critical ways, in constructive ways,” she said. “I like to think of my work as an opportunity for opposing energies … to come together.”

Starting in Houston in 2010, Cabrera’s community sculpture project “Space in Between” has traveled to several states, including a recent stint at the Desert Botanical Garden in partnership with ASU. Cabrera brings together members of immigrant communities to cut up U.S. Border Patrol officer uniforms and restitch them into life-size sculptures of cacti and other desert plants. They complete the sculptures by nestling them into terra cotta pots and displaying them together, creating a fabricated landscape that resembles their own environments.

“Immigrant communities select the plants themselves; they have experienced something in the vicinity of these plants,” she said. “They embroider the story of their own experience.”

Cabrera’s project has many layers, from the community element behind the actual creation of the sculptures, down to the fabric of the uniforms which she said is a weaving of threads indicative of the community interactions she hopes to foster with her the pieces.

Cabrera sources the uniforms from the same vendor where U.S. Customs and Border Protection gets its officer uniforms.

“We cut them up and we give them new forms,” she said. “The uniform is a symbol that creates this sense of resistance; it stops people in their tracks, gives us a sense of exclusion. It kind of brings up that whole anti-immigrant rhetoric that we lie within as an immigrant community, so we wanted to change that.”

Despite cutting up the uniforms, Cabrera maintains she intends no ill will toward border patrol officers with the project. She said the project has been successful because people have been able to come together and share their different perspectives and understandings of the uniforms.

She said the process of making the sculptures, the sculptures themselves, and the discussions that the pieces foster when they are on display are all part of the exhibition.

“This is not again a sculptural exhibition,” she said. “This is a community collaborative project that has to be seen in its completeness.”

She said carrying out this project here under President Trump has been particularly impactful because so many of the people involved want to change the national perception of Arizona.

“We have seen Arizona take the role of the state that is anti-immigrant on a national platform,” she said. “It’s been amazing coming in and having this perception of Arizona and meeting people who want to change that image.”

“This is the time in our country … where we need to create these platforms, and we need to bring different communities together,” she said.

The painter

The girl was stuffed inside a Powerpuff Girls piñata in an attempt to hide from border patrol officers and get across the border from Mexico into the U.S.

Pinata 07 by Julio Cesar Morales shows a little girl who was put inside of a Powerpuff Girls pinata. The painting was based on a true story that inspired Morales’ watercolor series. (Photo courtesy of Julio Cesar Morales)

That’s what Julio César Morales saw in the news about 10 years ago when he was inspired to start his ongoing watercolor series showing failed human smuggling attempts. Morales bases most of his paintings on actual stories of human smuggling that he finds online and in documentaries.

He said he likes the juxtaposition of the harshness of the content with the gentleness of the medium.

“To me, the softest medium in art is watercolors,” he said. “I wanted to represent those images – and that struggle of people trying to reunite with their families here – in watercolors.”

Morales said he was surrounded by human smuggling where he grew up in the Zona Norte neighborhood of Tijuana, Mexico. He knows of an auto body repair shop in Tijuana where customers can pay to have the workers take out a car’s dashboard, fit a person inside it, and then replace the dashboard so the person is concealed – or get sewn into the car’s seats.

“Those kinds of ways to get across have always been there,” he said. “Regardless if you spend $8 billion or $19 billion on a fence, people are always going to try more creative ways to get across.”

Undocumented Intervention #6 by Julio Cesar Morales shows a man who was sewn inside of a car seat. (Photo courtesy of Julio Cesar Morales)

His work has inspired observers to tell him their own stories of immigrating to the U.S. While he said it doesn’t convey a specific message at face value, his work intrigues people through its aesthetics into engaging with the larger socio-political ideas he tries to convey.

“In a way, I’m trying to tell this story about struggle and resistance, but I do it in a more abstract way,” he said. “Sometimes, it’s better to have strategies that are a little less direct in that sense.”

Morales, who is also a curator at the ASU Art Museum, said a lot of artists who based their work in social issues have gotten more recognition since Trump was elected, particularly in university museums where they respond to the receptive audiences of college campuses. He said these socially-based exhibitions are getting more attention nationally and internationally.

“Usually artists are the first in society to mark what’s coming, what they feel is the future for their community,” he said. “I’ve seen super positive, amazing artwork coming from Phoenix that is really responding to a lot of the current administration’s agenda.”

The seamstress

There isn’t much room to move around in Annie Lopez’s home studio. Tables of various tools and supplies jut out into space while vintage advertisements and photographs cover the walls. Racks of blue, paper dresses – made for her most recent exhibition, “True Blue” – occupy one corner of the room.

Lopez has been sewing since she was 8. As she got older, she discovered a passion for taking photos and, eventually, creating cyanotype – a chemical printing process that incorporates sunlight to create bright blue images. For “True Blue,” Lopez utilized a material used for wrapping tamales to make the dresses more resistant to the environment.

Phoenix artist Annie Lopez stands with some dresses made for her “True Blue” exhibit in her home studio. (Photo by Sarah Jarvis/Cronkite News)

Lopez uses documents and images meant to convey a social message, as well as pieces of her own life. Old advertisements, family photos, and legal documents are transformed and sewn into vintage dress patterns.

Lopez said the personal aspect of her work is cathartic, and that she’s come to think of the dresses as armor.

“I’ve always felt that whatever I make if I’m doing it about a bad experience if I put it into the piece, I’m no longer carrying that burden,” she said. “I’ve sort of sent it away.”

Lopez said that even if people can’t directly relate to the social commentary of the documents and images she incorporates into her work that often they can at least relate to the style of the dresses. She uses common dress designs from the 60s and 70s.

For Lopez, the arts are an important platform for expressing political messages to larger audiences.

She said Trump’s plans to eliminate funding for the National Endowment for the Arts is akin to ISIS destroying artworks and cultural icons. She said the Trump administration doesn’t understand the value of the arts.

“The more things that happen, the more we can start getting active,” she said.

But Lopez said she has been reacting to politics through her art for years. During George W. Bush’s first term, Lopez consistently made satirical and artistic prints of the president for what she had hoped would be his farewell. Despite his eventual re-election, and the election of Trump, Lopez said she’s holding out hope that “enough people make enough fuss” to change his policies.

“We’re going to do art,” she said. “We’re going to always express ourselves, so (Trump) should probably pay attention or listen up.”