Attendees watch speakers perform a role-play scenario instructing what to do if someone is undocumented and pulled over by police for a traffic offense. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

A woman records video of the speakers during the informational immigration event at Central High School. A district official said it’s not uncommon for people to take these videos to other undocumented immigrants who were too afraid to come to the meeting. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

Sixto, who asked to be identified by only his first name, is undocumented and has three children who are American citizens. He attended the immigration informational event at Central High School and said he hopes more people in his community will attend events like these in the future. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

A man and boy listen to presenters during the informational immigration event at Central High School. Organizers distributed the green folders, which have forms for parents to make arrangements so their kids don’t end up in foster care if the parents are deported. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

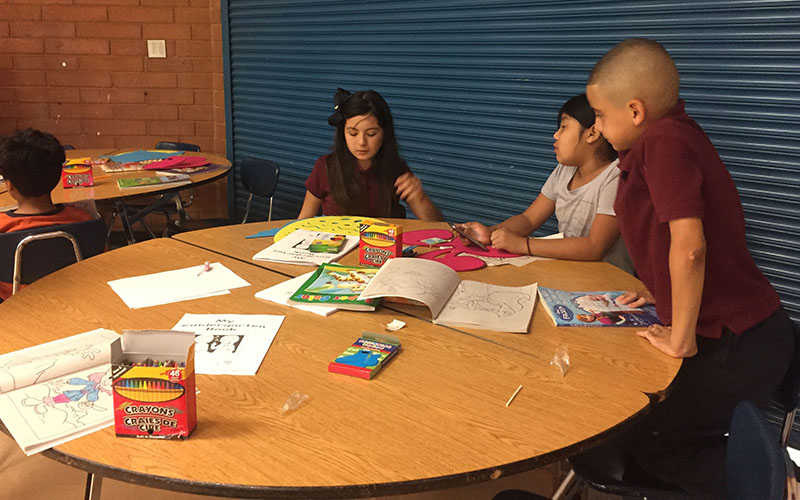

PHOENIX – Children kept themselves busy with coloring books and chased each other with masks in the corner of the cafeteria at Isaac Middle School, but school had long since ended and adults soon came over to keep them quiet.

Parents sat in rows of chairs across the large room and listened intently to a presentation in Spanish, detailing how they can keep their families together if faced with deportation.

Community meetings like this have cropped up across Phoenix in recent weeks, quantifying the heightened levels of uncertainty brought on by President Trump’s calls for tougher immigration enforcement.

Then came several high-profile deportations, including Guadalupe Garcia de Rayos of Mesa in February and recent reports of Juan Manuel Montes-Bojorquez, who was supposed to be protected under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix, hosted the Isaac Middle School event, which took place mid-April and had about 80 attendees. He said this wasn’t his first community meeting about immigration, but he sees families getting more and more scared and hopes he can help provide some clarity.

Children keep busy in the corner of an event hosted by U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego, while their parents listen to speakers about what to do if immigration officials come to their homes. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

“People are starting to draw plans about what happens to their children in case they get deported,” he said. “There are people avoiding dropping their kids off at school, they’re avoiding going to church because they’re hearing rumors that there’s deportation posses out there picking up people.”

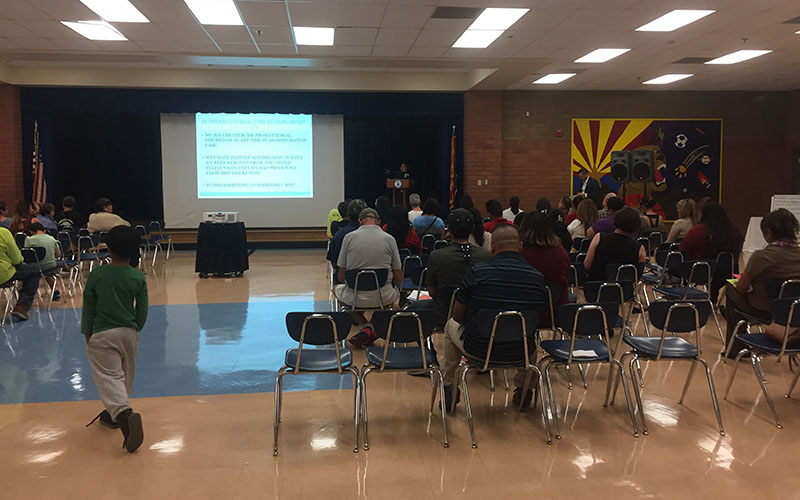

Gallego’s event followed a similar March event put on by Promise Arizona, an immigrant rights advocacy group. Then April 18-20, Phoenix Union High School District hosted three immigration forums at South Mountain, Maryvale and Central high schools. Many of the district’s schools have a high percentage of Latino students.

Sixto, a local painter who attended the Central High School event, said it was informative and helpful. He has three children who are U.S. citizens and asked to only be identified by his first name because he is undocumented.

“I do feel some nerves because of everything that’s happened,” he said in Spanish. “… All of us who came here did so with the end goal of progressing forward, of working, and to do no harm to anyone.

“Yes, there are people who come here to hurt others, and this might sound bad, but they should be punished or they should pay. If they come here to hurt, they should pay for it. And those of us who come here to work, we should be understood and rewarded for that,” he said.

Sixto said he hopes to see more people come to these events. Around 50 to 60 people signed in on each of the three nights and attendance was open to the public.

“There does need to be more collaboration on our part,” he said. “More of the community needs to come out to these types of events. Sometimes I don’t see much enthusiasm in our people.”

At both Gallego’s and the district’s events, organizers passed out flyers that explained the do’s and don’ts if Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents show up at the front door. For example, families should not allow ICE to enter without a warrant, should not answer questions without a lawyer and should take pictures or video of the interaction, the advocacy groups said.

Abril Gallardo speaks about the legal process for parents to make arrangements for their kids in case the parents are deported. She is undocumented and a DACA recipient. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

At the Phoenix Union High School forums, families also received a packet of legal forms that would allow them to set up arrangements for an attorney in case of deportation proceedings, as well as to establish a legal guardian to take custody of children if their parents are deported. The district has paid notaries on every campus to notarize these forms.

Cyndi Tercero, the student support services manager for the district, said although attendance was a little lower than expected, these events will have a ripple effect.

“If we’re helping and serving 10 families, or 100 families, we feel that we did something,” she said. “And we know that there are families that came last night and they took the information and they said, ‘Now I can have this to take to my neighbors,’ who maybe were too afraid to come out or maybe just didn’t have the time to come out.”

Immigration concerns are connected to the schools because students who are worried about their parents being deported won’t be able to focus on their studies, Tercero said.

Abril Gallardo graduated from one of the district’s high schools in 2009 and is undocumented and a DACA recipient. She spoke at the event, instructing parents how to make legal arrangements to make sure if they are deported that their children don’t end up in the foster system.

An immigration attorney instructs members of the public at Isaac Middle School in Phoenix about the rights of undocumented immigrants when confronted by immigration officials or deportation proceedings. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

She said she wishes she’d had these events when she was younger.

“We didn’t have these conversations; we were never open about our status,” she said. “… I think being in high school, undocumented and not being connected to groups was a really scary and lonely process and I am really excited and grateful to see that there’s a bridge now and students like me can go to their schools and they will find the support that they need.”

Gallardo said she’s always worried about her family being separated but it motivates her to do more.

“Thinking that you are protected and somehow your parents can still go to work and then might not come back … it’s a sense of responsibility that I must continue to fight for my community to achieve some kind of relief for them, and not only for them but for 11 million people who are here in the United States without documents,” she said.