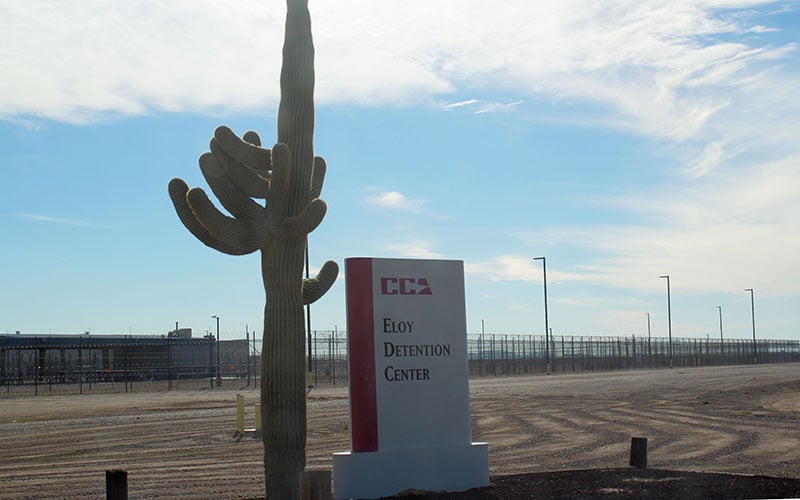

The Eloy Detention Center is located 65 miles southeast of Pheonix and houses more than 1,500 inmates. (Photo by Charlene Santiago/Cronkite News)

ELOY – Sandra Ojeda is familiar with search procedures and the visitor registration process at the Eloy Detention Center.

She carried nothing but a sheet of paper with the names of six U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees and their A-number — identification issued by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to undocumented immigrants.

She assigned one detainee to each first-time visitor.

Welcome to one of the country’s most controversial detention facilities where young immigration advocates make time to visit men and women they have never met before.

Four college students arrived with Ojeda at the privately-owned detention center about 65 miles southeast of Phoenix. They had no prior relationship with the people with whom they would spend an hour talking on an early Saturday morning. The students were nervous and uncertain, but Ojeda guided them through the process.

Yvonne Bueno, a sophomore at Arizona State University, visited for the first time and said she made the trip from Phoenix not knowing what to expect.

“I went through with it because I knew it was important,” she said.

Bueno was assigned by Ojeda to visit Jorge Castillo. According to Bueno, Castillo has been detained in Eloy for approximately 16 months when they met. Visits are promised to last at least one hour, but they vary depending on the number of visitors waiting in the lobby.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainees gather in the courtyard at the Eloy Detention Center. (Photo by Charlene Santiago/Cronkite News)

As the hour passed slowly for Bueno, she said Castillo did not have much to talk about. Bueno said she noticed how Castillo showed his lack of trust through silence. She couldn’t avoid feeling helpless, she said.

“I sat there knowing there isn’t anything I can do to help these individuals get out, but I wanted to try my best to do anything I could,” she said as she recalled her experience.

Juan Cornejo, a former Eloy detainee, said visits are important for an inmate’s mental and emotional health.

“It’s a daily mental battle when you’re in there,” Cornejo said as he recalled his incarceration.

Now free and seeking asylum, Cornejo and his wife Ojeda organize and coordinate regular visits to Eloy as an act of support and solidarity. Cornejo said he appreciated the time volunteers invested in accompanying him when his family couldn’t make the trip.

“Visit hours are times for you (detainee) to breathe, feel calm, and forget about the problems that haunt you in there (the prison),” he said.

Ojeda is notified by inmates of fellow detainees who haven’t had many visits. Sergio Ledezma Caballero has been detained for two years and provides Ojeda with names and A-numbers of detainees. Ledezma Caballero himself has received visits from volunteers.

Ledezma Caballero is being treated for depression. His father passed away in November and his wife Adela Lozano is suffering from a pulmonary embolism. As she takes care of her two teenage sons, Lozano isn’t able to visit every weekend and Ojeda assigns Ledezma Caballero a visit from a volunteer.

Giovanni Cisneros, a first-time visitor, recognized the importance of the visits. Cisneros said he went with the intention to help the detainees gain some sense of humanity, “by simply being there and showing them that I care,” he said. His experience was different from his peers.

Cisneros wasn’t able to visit an inmate because he didn’t have proper identification, but he saw family members registering as visitors, waiting in despair to see their loved ones.

“I had no expectations when I went, but what I saw was the destruction of families,” Cisneros said as he recalled seeing kids and families leaving their visits with tears in their eyes.

Sandra Cornejo, 19, arrived with Cisneros and Bueno for the first time as a visitor. She knew what to expect. She had already experienced visits in Eloy with her mother Ojeda, when her father Juan Cornejo was detained for eight months. She said visiting a stranger was different than visiting her father.

“Visiting my dad, there was a feeling of hopelessness,” Sandra Cornejo said. “While visiting a stranger, I felt as if I had some sort of power.”

From her father’s experience, she said she learned the importance visit hours can be for a detainee’s day-to-day uncertainty.

Visitors make their way in to the Eloy Detention Center. (Photo by Charlene Santiago/Cronkite News)

Sandra Cornejo visited a young man who introduced himself as Juan. She said she was surprised to meet somebody under ICE custody that is her age and a father of twin girls. She said he was taken into custody by ICE when he was 18 and almost close to his high school graduation.

“I cannot imagine how hard it must be to have your freedom ripped away from you,” she said as she recalled her conversation with him.

Although she said she was helping the detainees, Cornejo said she couldn’t avoid thinking “what if” after every visit as a daughter and after her first time as a volunteer.

“There is a worry of leaving them behind, “she said. “There have been many deaths in detention centers and every time I leave Eloy, I wonder if the person I just visited could be the next …”

The detention center has made national headlines for its troubling conditions and its high suicide rates. As of 2015, Eloy accounted for 9 percent (14 deaths) of the nation’s deaths in detention centers in the past 12 years.

Since 2013, volunteers have carpooled to detention centers in Arizona. Currently, the Puente Human Rights movement, which sponsors the deportation visits, is running an online fundraising campaign to purchase a new van that will provide families with reliable transportation to the immigration facilities.

Despite transportation challenges, Juan Cornejo said volunteers will continue to make regular visits as well as driving those who have detained family members.

“We will keep visiting, with or without a van,” he said in Spanish.