Immigrant families show off their artwork after a healing workshop to help undocumented immigrants and their relatives deal with a mix of emotions including anxiety,fear and hope. (Photo by Mindy Riesenberg/ Cronkite News)

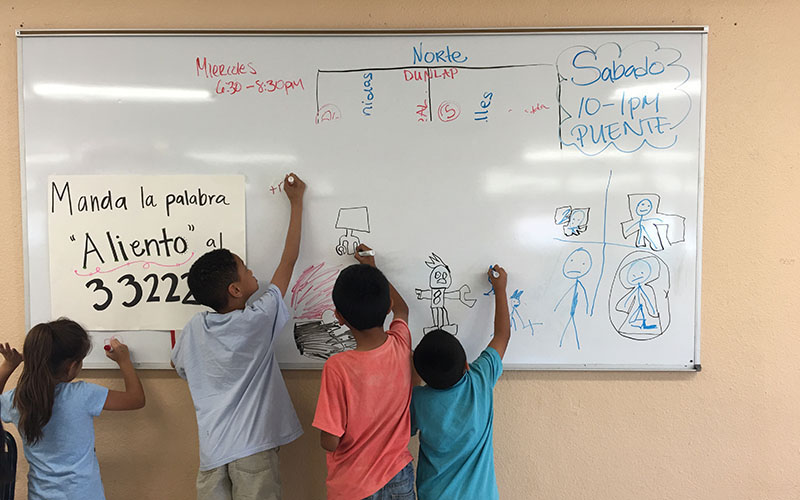

Phoenix— “No estamos solos,” words meaning “we are not alone,” rang out at an art workshop for undocumented immigrants and their families led by Aliento, an organization that uses art to promote healing.

“This is a space where undocumented families can process and talk about their emotions and express them through art,” said Reyna Montoya, 26, founder of Aliento, an organization that seeks to promote healing through art.

Montoya recalled the isolation she felt as a 13-year-old undocumented immigrant from Mexico living in Arizona.

“Nobody understood me,” she said. “I didn’t know enough English and people made awful jokes at school about Mexicans. But my parents were my biggest cheerleaders. If I didn’t have them, maybe things would have been totally different,” said Montoya.

She is protected from deportation by DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, but knows many others are not and live in fear.

This emphasis on family ties and support led her to create Aliento (“breath” in Spanish), using art to help undocumented families work through the emotions surrounding immigration, detention and deportation.

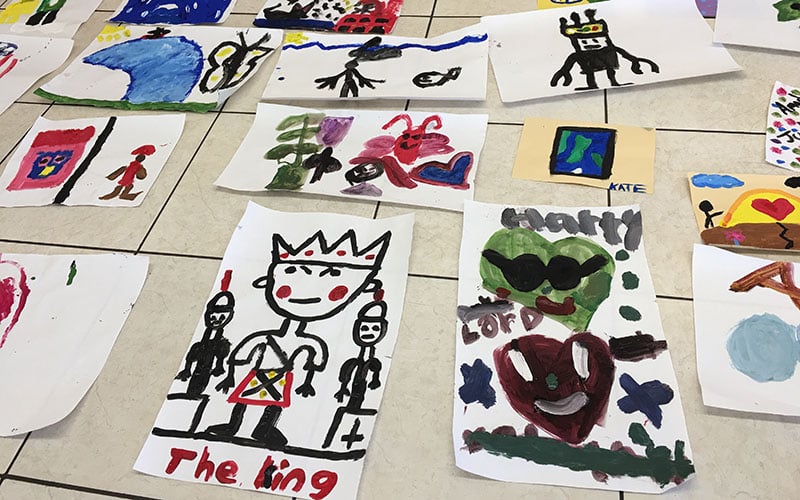

At the Art and Healing Workshop: Colors and Emotions held on a recent Saturday morning, children and their parents painted colorful images of butterflies, happy faces and robots, bringing to life the feelings of joy, hope and love.

But some of the artwork also reflected anxiety and fear. One child painted an image of a yellow-haired Donald Trump addressing a crowd to depict the word anxiety, and another young boy drew what he called a “bad king” wearing a crown to express the word fear.

Art historian Theresa Avila, one of the facilitators, pointed out that undocumented families are a challenging group to work with because they’ve often experienced violence during their journey to the U.S. and are now coping with the fear of being deported.

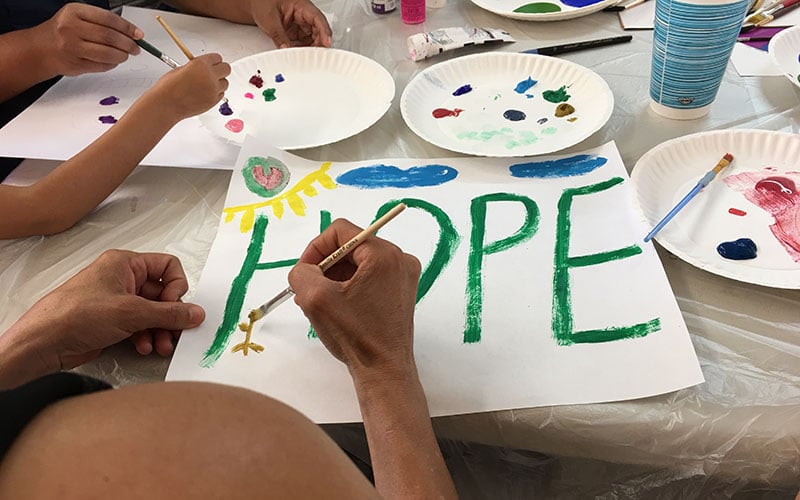

“This is a creative way of processing what these families are dealing with,” said Avila. “One of the mothers here was depressed, but showed up anyhow with her kids. The daughter started painting something black and I became worried, but then she added purple and glitter and wrote about reaching for the stars. The kids always turn it around and find the silver lining.”

“A lot of the parents are scared,” said Ezequiel Santos, an organizer with Aliento who participated in the workshop. “They want to make sure their children are prepared in case they are detained or deported.”

By creating works of art expressing the range of emotions they are feeling, the participants are able to release some of the anxiety and stress they carry with them from day to day, according to organizers.

“I’m scared because I’m finally getting to this point of the American dream, and now it can be taken away,” said Santos, who is undocumented and is a DACA recipient. “And it’s horrible that the kids here have to worry about whether or not their parents will be deported.”

At the end of the three-hour workshop, an array of colorful paintings lined the floor, drying in the warm spring air.

“We all need to connect at a human level, to see how policies are impacting real people,” Montoya said. “Through art, these families can show how they feel without saying what’s exactly wrong.”

Montoya gathered the families into a circle and asked each person how they were feeling. The organizers did not want the workshop participants identified by their names.

“Contento (happy),” said one little girl in a bright pink shirt.

“Tranquilo (tranquil),” one of the mothers said softly.

“Unido (united),” said Santos with a grin.

A smile spread across Montoya’s face as she listened to this common refrain of peacefulness.

“I think that when people think about undocumented families, they think of anxiety and fear,” Montoya continued. “But what I see is their resiliency and how beautiful they are.”