TUCSON – The next generation of space telescopes will launch next year, and two Arizona scientists helped create critical instruments attached to the telescope that they hope will detect the beginnings of the universe.

The James Webb Space Telescope will launch from French Guinea, the culmination of a joint venture between NASA, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, various private space exploration companies and University of Arizona scientists.

The telescope is ambitious in its design, its goals and its launch. It will go farther into space and capture more information than any other space telescope so far. Workers will have to fold it up to fit in the rocket because its 18 beryllium-gold mirrors are larger than its rocket.

Marcia Rieke, a professor of astronomy at University of Arizona, sits in the office she has had at UA since 1984. She developed an infrared camera used to capture planets and light from farther away. (Photo by Courtney Kock/Cronkite News)

Marcia Rieke, one of the key scientists, describes the goals of the launch: “(We want to find) the first universes to form after the Big Bang, and if we should be so lucky, to prove an exoplanet is Earth-like.”

Essentially, they want to see whether there’s the potential for life on other planets.

Marcia Rieke and her husband, George Rieke, are regents professors of astronomy at the University of Arizona, and they have spent the past decade of their lives on this project. The two have led separate teams that built cameras on the Webb.

Marcia Rieke was the first of the two to submit a bid for a contract.

George Rieke laughed when he described how he wrote his proposal back in 2002: “I figured, well, they certainly won’t pick both of us, but maybe as insurance, I’ll just turn this thing in.”

It turns out NASA did want both projects, but they had a caveat for him: If funding dried up, they would have to drop his instrument.

George Rieke said that just made him and his partner, Gillian Wright, work harder.

George Rieke, a professor of astronomy and planetary sciences at the University of Arizona, was one of the lead scientists developing the Mid-Infrared instrument, MIRI. (Photo by Courtney Kock/Cronkite News)

“My theory, is that because we were under such threat, we bonded as a team,” he said. “And it really helped bring us together. Not that I recommend this kind of stress. … That’s why we take a lot of pride in being the first instrument delivered.”

George has built infrared telescopes since 1976, but the Earth’s ambient heat hindered his work. With the Webb launching into an orbit farther than other infrared space telescopes, it will nearly eliminate that interference, he said.

The University of Arizona is one of the leading universities in space contracts with NASA, having created four research instruments for the space agency. “There’s no other university that’s been responsible for more than one,” George Rieke said. “We became the world center for infrared astronomy, before it really had gotten started.”

Originally called “The Next Generation Space Telescope,” the Webb has been likened to the Hubble, the world’s most recognizable space telescope.

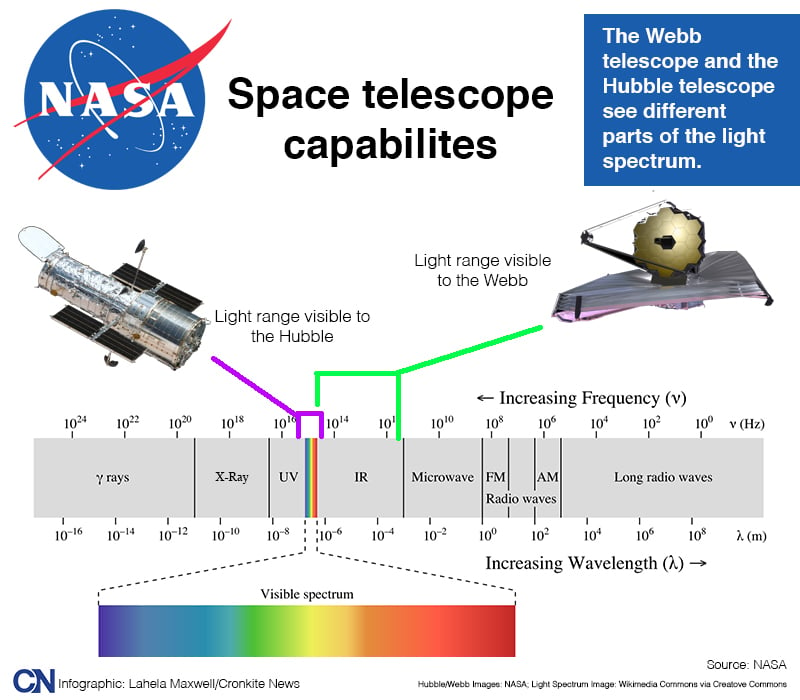

However, experts said there are key differences. The Hubble and the Webb are engineered to perceive different ends of the light spectrum: The Hubble sees purple light, and the Webb will see red light. The Hubble also resides in low-Earth orbit, which means scientists periodically lose contact with it as it moves around the Earth. The Webb is set to orbit the sun instead, so it remains in constant contact. Scientists believe that light from the far reaches of the universe eventually stretch out and move into the infrared end of the spectrum – that red-light area – because of the constant expansion of the universe. That means the Webb will see farther out into space.

Marcia Rieke’s instrument, the Near-Infrared Camera, will be able to take pictures the Hubble never could.

“A good analogy is: Say that you don’t feel good, (and) you go to the doctor. Is the doctor only going to take your temperature? No. He may do some other things. He’ll take your temperature. He’ll measure your pulse. He might take a sample of blood. … He might take an X-ray,” Rieke said. “To diagnose someone, what’s going on somewhere, you need a whole range of information.”

The Webb will provide that extra information.

George Rieke’s instrument, the Mid-Infrared Instrument, reaches a range past his wife’s camera.

This opens up the possibility for MIRI to capture even more, such as stars being born in gaseous clouds of dust and hydrogen.

Infographic that illustrates the light spectrum range capability of the Hubble and Webb telescopes. (Graphic by Lahela Maxwell/Cronkite News)

MIRI can detect the building blocks of life through spectral imaging. “All of the organic materials that go into making life, the very first steps, have spectral characteristics in the MIRI waveband,” George Rieke said. “We won’t be able to see DNA or anything like that. We’ll see methane, the basic starting points for building up life.”

The Riekes said the Webb also utilizes a unique cooling system that will allow the telescope to reach a similar temperature as open space. That’s important because these cameras will pick up ambient heat from Earth, the sun and itself – and that clouds the readings.

“You need to be sure that it’s seeing (infrared) light from dim, distant objects, not from itself,” Marcia Rieke said.

The University of Arizona is looking to “learn about the universe,” she said. “It provides a wonderful basis for people to further their own research programs … but the fact that some of us here worked on the instruments, we know how best to use them. And of course, my team here is getting funding to pay salaries from now ‘til 2022.”

The project not only boosts the university, it also helps the aerospace industry, they said. Several other companies provided parts for this project, ranging from lenses, chips, bearings and exotic metals such as beryllium. “The number of companies that we have bought stuff from is … large. Ten big companies, and at least a hundred little ones,” she said. Her team used companies from across the country, including Arizona companies and the University of Arizona machinist shop.

Currently, both Marcia and George Rieke’s instruments are attached to the Webb telescope at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. They’re going through vibration testing to simulate rocket launches. Later, it will be delivered to the Johnsons Space Center in Houston, Texas, for further testing. The telescope is set to launch in October 2018.