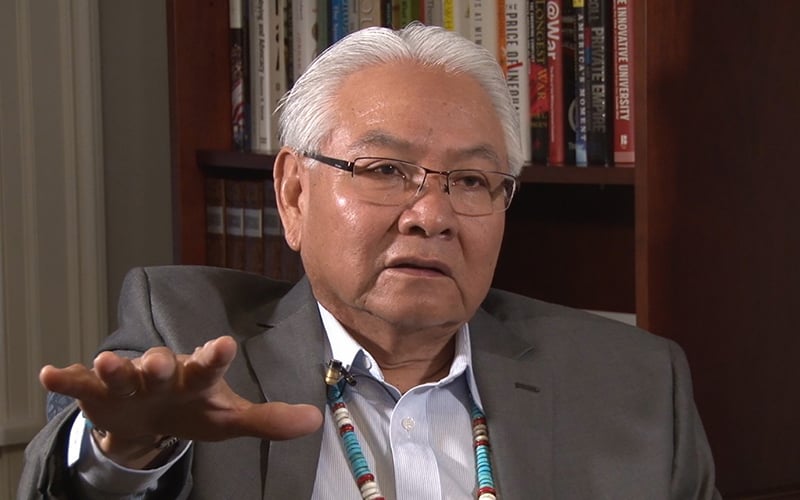

Tommy Lewis, the superintendent of schools for the Navajo Nation, said he worries that changes under the Trump administration could hurt tribal schools, particularly the calls by some to increase school choice and do away with Head Start programs. (Photo by Marisela Ramirez/Cronkite News)

Lindsey Burke, director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, said that rather than more “large federal programs” like Head Start, funds are better spent on programs to directly “fund the child” like vouchers and education savings accounts. (Photo by Marisela Ramirez/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – The superintendent for Navajo schools said “alarming” calls for the Trump administration to eliminate Head Start funding could leave tribal children without preschool programs or the education resources they desperately need to succeed.

Diné Superintendent Tommy Lewis made the comments Wednesday during a wide-ranging interview in Washington that touched on his fears for education changes under President Donald Trump, from funding to school choice to tribal sovereignty.

But Lewis said the thing that worries him most is a Washington think tank’s call on the Trump administration to phase out Head Start, a federally funded preschool program that is worth $25 million a year on the Navajo Nation.

Navajo families have benefited Head Start since 1960 when the program was introduced on the reservation, and Lewis said parents and tribal leaders consider the program essential to children’s early growth and development of social skills.

“Our tribal leaders are beginning to realize that if we don’t take a position on Head Start, it’s really going to have an impact on our people,” Lewis said.

But an education expert with the Heritage Foundation, which made the budget recommendations to the new administration, said Head Start is not as effective as its supporters claim.

Lindsey Burke, director of Heritage’s Center for Education Policy, said an investigation by the Department of Human Health and Services showed Head Start to be ineffective. HHS funds Head Start.

“Head Start had no impact on children’s social emotional well-being, their access to health care, the parents’ parenting practices, all of these things that we would hope would improve,” Burke said.

Under the proposal put forward by Heritage, Head Start funds would be cut by 20 percent a year for five years, when the program would be eliminated.

Lewis noted that some students graduate from Diné high schools reading at a fifth-grade level and having a fourth-grade level understanding of math. He worries that without Head Start, Navajo children could fall even further behind and have an even harder time becoming successful as adults.

“Overall, I think it (school choice) is really going to hinder our programs,” said Lewis, who was in Washington for meetings with the Bureau of Indian Education and the National Indian Education Association, among others.

-Cronkite News video by Marisela Ramirez

He dismissed the report’s suggestion that the Head Start programs could be replaced by privatized preschool programs.

With consistently high unemployment rates on the Navajo Nation, Lewis said it is unlikely that parents could afford to send their children to private preschools.

Even if they could, those schools do not currently exist on the reservation, he said. On a reservation sprawling across parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, he said there are only three or four private K-12 schools.

But Burke said that could change if Navajo parents had access to school vouchers.

“It’s sort of a chicken-and-egg problem … students don’t have control of dollars, and so they’re not able to access private providers,” she said. “Private schools don’t pop up because the families don’t have the purchasing power.”

Proposals to extend vouchers to tribal schools could get a boost under new U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, a longtime champion of school choice.

Lewis said school choice may make sense in some parts of the country, but not in Indian Country where there are not schools to choose between.

“If you have the economic base, if you have the employment and if you have ways to take care of yourself, that’s probably the right thing to do,” Lewis said.

Not only are there few private or charter schools on Navajo land, he said, but the schools that do exist are at capacity and have long waiting lists.

Burke counters that voucher programs can be used for tutoring or online classes, not just private school tuition.

She said that school choice programs and privatized education will benefit students more than “large federal programs.” She said public dollars would be better used to directly “fund the child,” by encouraging education savings accounts and voucher programs.

But Lewis fears that school choice could siphon students away from Navajo schools, not only depriving the students of the cultural education that Diné schools pride themselves on but also depressing enrollments on which tribal school funding is based.

Schools are already struggling to make ends meet, he said, and with each student that leaves the system funding could decrease.

“Education is what we need, more than ever, so we can use it as weapons to combat all the problems we’re faced with at our home,” Lewis said.