PHOENIX — With President Donald Trump’s new enforcement of deportation orders, and the deportation of Guadalupe Garcia de Rayos last week, immigrant rights organizations in Arizona are stepping up their educational efforts so families will know what rights they have if a parent is deported.

“I think the impact of the executive order on families will be severe,” said Laurie Melrood, a volunteer family advocate based in Tucson. “If the kids don’t have other caretakers, who will care for them? I feel the government just wants to get the undocumented out and the consequences are of no interest to them.”

With this in mind, the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project is updating its guide “What if I’m Picked Up by ICE in Arizona.”

The guide, originally developed in 2014, was created in response to the significant number of parents the Florence Project was working with who had lost their parental rights because they were unable to participate in Department of Child Safety proceedings.

Yasmeen O’Keefe, public affairs officer for the Arizona office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said she was unaware of the guide and was unable to comment on it.

“Once a parent is in detention, it is incredibly difficult to facilitate communication between the detained parent and their children’s DCS caseworker and attorney because they are often entirely excluded from the court process,” said Beth Lowry, a caseworker with the Florence Project.

Lowry pointed out that the guide serves as an education and action tool for immigrant parents so they can understand their parental rights and make a plan of action before they are detained by immigration officials.

The bilingual guide is “a reader-friendly road map for what is a very complex and disorientating process,” Lowry said.

Families that use the guide find information on power of attorney, guardianship, local resources, advocates and consulates.

“We hope the guide will help families feel empowered, informed and prepared, and will promote family unity by preventing children of undocumented parents from falling into DCS custody,” Lowry said.

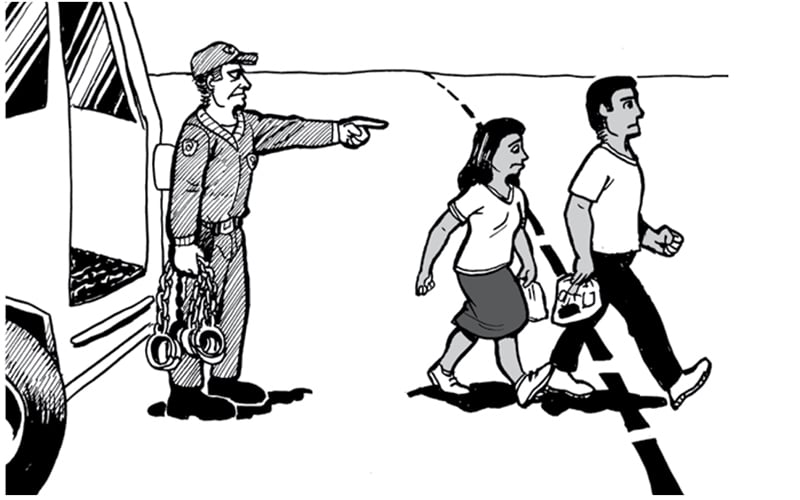

This cartoon depicting a mother who has been detained by ICE is included in a guide that helps undocumented parents prepare for the possibility of being detained, deported or separated from their children. (Courtesy of The Florence Immigrant & Refugee Rights Project)

The Florence Project goes into the community to provide free training sessions that accompany the guides. Participants usually walk away with notarized power of attorney forms and plans of action for their families.

Another group actively reaching out to immigrant parents and families is Paisanos Unidos, a Tucson-based “protection network.”

“A family alone can do so much, but families gathered together have more power in creating a safe space,” said Margot Veranes, a community organizer and volunteer for Paisanos Unidos.

Families get together for “cafecitos,” relaxed coffee gatherings where they learn about their rights and make sure they have their affairs in order. This includes having a designated person who will always pick up the phone in an emergency, having someone who is responsible for picking up the children if a parent is detained, and having a designee who has power of attorney and can show up in court with all the right papers.

This cartoon is included in a guide for undocumented parents to help them create a plan for their children in case they are detained or deported by ICE. (Courtesy of The Florence Immigrant & Refugee Rights Project)

Veranes said many of the people who go through the training end up becoming advocates for other families.

“It’s transformative,” she said. “Once they know what’s going to happen and have a plan, it allows them to focus on working to change things.”

They also go through training to learn how to represent themselves in bond hearings.

Before the president’s executive order was signed, most people who had been through the training were able to get out on bond because they had developed the tools to ensure they are safe.

But an air of uncertainty now hangs over the training.

“We don’t know what the government is going to do differently now, especially after what happened to Ms. Garcia de Rayos,” Veranes said. “Our goal now is ‘how can we spread information more quickly to other families?'”