Leila Asadi, an Iranian finishing her doctoral studies in the U.S. on an F-1 visa, is one of more than 270 students in Arizona who came from the seven countries identified in a temporary travel ban issued by President Donald Trump. (Photo courtesy Leila Asadi)

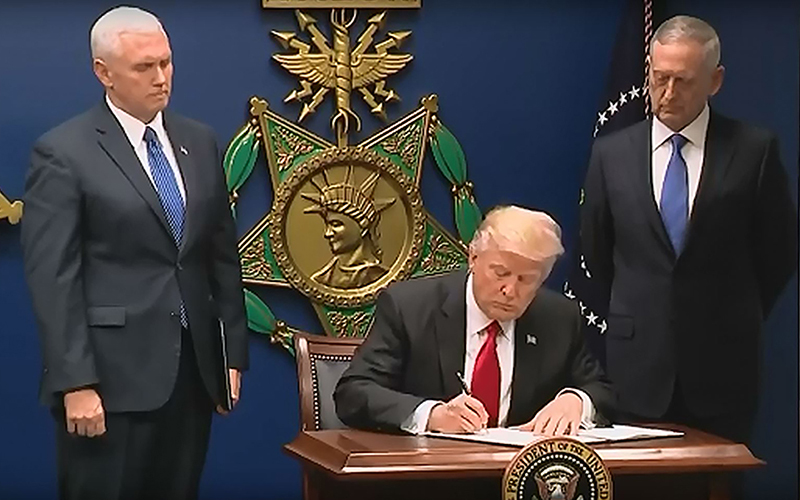

President Donald Trump signs an order blocking refugees and banning all visitors from seven countries, to give the U.S. time to review immigration policies. Vice President Mike Pence, left, and Defense Secretary James Mattis look on. (Photo courtesy the White House)

Protesters rally in Washington, D.C., after President Donald Trump signed an order targeting visitors from seven majority-Muslim countries. Critics said it targeted Muslims, while the White House said it was aimed only at improving U.S. security. (Photo by Ted Eytan/Creative Commons)

WASHINGTON – Leila Asadi has had to put her doctoral dissertation on hold while courts consider legal challenges to President Donald Trump’s temporary ban on travel from seven majority-Muslim countries.

Asadi, a justice studies student at Arizona State University, is an Iranian who hoped to go to the Middle East to interview Syrian refugees for her dissertation – but might not be able to return if she left the U.S., as those are two of the countries targeted by Trump’s order.

She is one of more than 270 international students from the seven nations currently studying at one of Arizona’s three public universities students who, like Asadi, are “in limbo.”

The ban, signed Jan. 27 by Trump, bars admission of any refugees for 120 days and any visitors from the seven countries – Somalia, Syria, Sudan, Iraq, Iran, Libya and Yemen – for 90 days.

The White House called the order “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” but critics quickly attacked it as unconstitutional and aimed at Muslims, a move they said would make the nation less safe by inflaming Islamists.

The order was quickly challenged in court and a federal judge in Washington state blocked enforcement of the ban last week. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals refused an emergency request to lift the ban over the weekend, and heard arguments Tuesday from attorneys for the state of Washington, which challenged the order, and the Trump administration.

The court had not issued a ruling as of Tuesday evening.

For now, with the order blocked, people with visas from those seven countries can come to the U.S. or, like Asadi, could return if they left the country.

But Asadi said she was not hopeful that the court will deliver good news for visa-holding students like her. She remembers feeling both awkward and sad after hearing about the order.

“I just kept thinking, ‘Oh my God, what a world we live in,'” Asadi said.

Official reaction at the state’s three universities ranged from explicit opposition to calls for a more thoughtful policy that protects families here and protects the ability of students and scholars to continue their work.

At Arizona State University, where 160 undergraduates and 31 graduate students from the seven targeted countries are enrolled, President Michael Crow sent an email to faculty Jan. 30 touting the “fantastic, almost unbelievable, outcomes have been achieved by immigrants who attended American colleges and stayed in this country.”

The email, forwarded to students on Feb. 3, was a response to what he called “the many messages and comments” he received on Trump’s order.

“Little thought appears to have been given to the individuals and/or mixed nationality families already holding valid visas or green cards from those countries, not to mention the many thousands already in the U.S. with many of them students at American universities, including ASU,” Crow said in the email.

University of Arizona President Ann Weaver Hart came out in explicit opposition to the executive order and said in a Jan. 29 statement that she was confident “that lawsuits challenging it will be successful.”

Still, she said she was aware of the fears that international, visa-holding students at the university may have and advised international students to avoid traveling for the time being.

A fact sheet from the University of Arizona’s Global Initiatives said the school has 81 students from the “banned” countries, 70 of them in graduate programs.

Northern Arizona University officials said there are fewer than 10 students from the targeted countries on their campus, but could not provide an exact number.

“We are maintaining close contact with our international students,” said NAU spokeswoman Kimberly Ott, who said the university is doing its best to understand the premise of the executive action and stay on top of the facts.

In a Jan. 30 statement, NAU President Rita Cheng said university officials “understand and are committed to the protection of our national security and believe a strong and effective visa process will support economic competitiveness and prosperity.”

But the statement went on to say, “We encourage the adoption of policy initiatives that allow NAU to educate and collaborate with students and faculty in Arizona and throughout the world.”

A day later, Cheng joined in an American Council on Education letter that said signers were “confident that our nation can craft policies that secure us from those who wish to harm us, while welcoming those who seek to study, conduct research and scholarship, and contribute their knowledge and talents to our country.”

For now, all Asadi can do is wait.

She came to the United States in 2011 on an F-1 visa, after she said she was harassed by the Iranian government for her advocacy for women’s rights there.

She said her visa has expired but she can remain legally in the U.S. under the I-20 program until August 2018 while she completes her studies. She planned to go to the U.S. Embassy in Dubai to apply for a multiple-entry visa, which would let her to travel to Jordan, Turkey and other countries where Syrian refugees are living in camps.

Those plans changed with the executive order. She will look for Syrian refugees here for her dissertation – which looks at what humanity’s obligation is to refugees and victims of tyrannical governments.

While Asadi is worried about her own freedom and research, she is “overwhelmingly concerned for the public.”