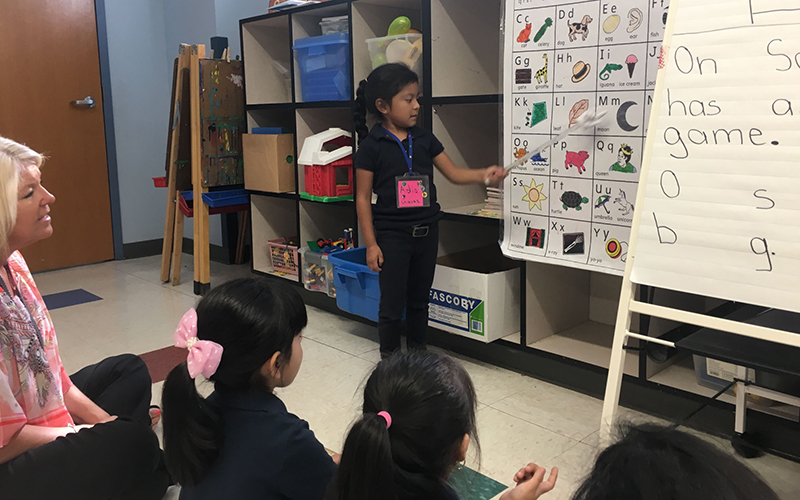

Students in this kindergarten class are English-language learners whose native language is Spanish. They expected to become proficient in English by the time they finish the school year. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Marissa Chavez’s kindergarten students often play teacher, taking turns pointing to an alphabet card while the other students sit cross-legged on the floor.

“M-m-m-m-m,” they chant, sounding out the 13th letter of the alphabet.

“It looks like they’re playing, but they’re not,” Chavez said. By the end of the school year, Chavez said, these English-language learners should speak English fluently.

Chavez, a teacher at Bret R. Tarver Elementary School, said that is likely to happen because her 25 kindergarten students are in class for 6 1/2-hours a day, or full-day kindergarten. The optional program is much longer than the state-required half-day kindergarten, which amounts to 2 1/2 hours in the classroom.

“I have ten kids who are reading. And then I have some kids who are still learning. But with a full-day program, I’m able to meet both of their needs,” Chavez said. Her students also are learning math, science and social studies.

Teacher Marissa Chavez said students in full-day kindergarten learn socialization as well as academic skills. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News).

Chavez remembers teaching half-day kindergarten when she started her 12-year teaching career in 2004.

“We were really pressured to just teach reading readiness skills and maybe just a little bit of math,” Chavez said. “Now that it’s a full-day program, we’re able to teach a balanced literacy program.”

The perennial debate over full-day kindergarten in Arizona has an added twist, with some educators, community and business leaders saying academic standards need to be applied to a full-day program.

The right program can prepare students for first grade, help them develop social skills and regulate the curriculum so students across the state enter first grade with the same basic skills, advocates say. The push towards full-day program expectations comes partly from evolving state standards and Common Core requirements for first graders.

But not everyone likes full-day programs, with some saying they have little impact, push children who are just getting used to school and are a waste of money.

How full-day kindergarten works

Title I schools for disadvantaged students use state funds to pay for full-day kindergarten. Other schools only offer full-day programs if parents pay for it.

The Arizona Department of Education doesn’t keep data on full-day kindergarten because schools are only held accountable for the first 2 ½ hours of learning. Information is scarce on how many schools in Arizona provide full-day kindergarten, what they teach, or how many hours students are in class.

Renee Parker, principal at Sirrine Elementary School in Mesa, a Title I school, said students who come from low-income families often don’t have the same experiences as other students, such as parents who have the time and income to be more involved in their children’s development.

Renee Parker, principal of Sirrine Elementary School, said education standards have changed greatly since she started as an educator 22 years ago. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam, Cronkite News)

“Those students do come in sometimes at an academic disadvantage,” said Parker, who has been an educator for 22 years. “They never held a pencil before. They don’t have many of those experiences of many kids who…went to preschool.”

Parker said students learn more than just arithmetic and reading skills.

“You’re teaching all those social skills along with those academics,” Parker said. “The younger you are, the easier it is to learn those things.”

Education and business leaders spoke about the benefits of setting academic standards for all-day K at an Arizona Board of Education meeting in October.

One reason would be continuity among all-day kindergarten programs.

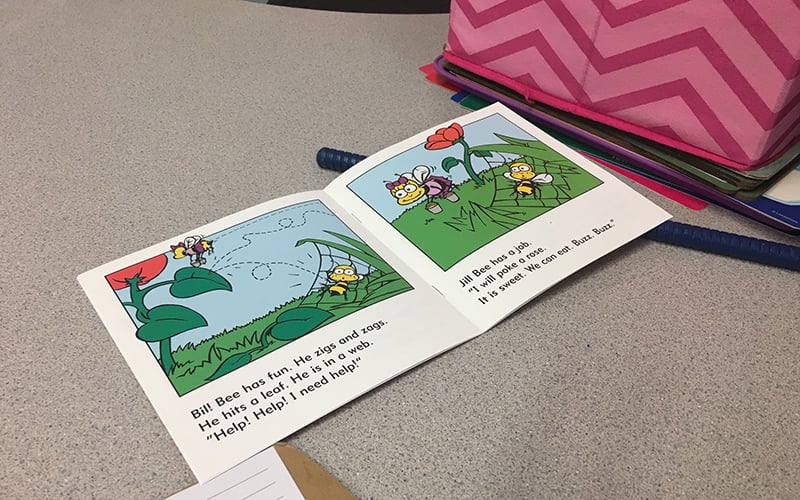

Some schools, like Tarver, teach kindergarten students from bell to bell. Chavez said her kindergarteners learn reading comprehension, writing, math, science and social studies. They also attend classes in art, music and physical education.

But, because there are no learning standards past the required 2 1/2 hours, not all schools set high academic expectations. Sen. Steve Smith, a Republican who represents District 11 in Pima County, said at the meeting some constituents who paid for for full-day kindergarten were unhappy.

“They played games. It was effectively babysitting time,” Smith said. “They did not have the same teacher as they did the first half of the day.”

“For me as a parent, to want to put my child in all-day K, there had to be some sort of actual achievement and learning going on the second half of the day,” Smith said.

Philip Francis, former chief executive of Petsmart and an advocate for full-day kindergarten, said regulating all-day programs would make it an essential early step in Arizona education.

Full-day kindergarten students learn to read using picture books, teacher Marissa Chavez said. “If we taught for 2 1/2 hours (a day) there’s no way that we could get most of them there.” (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News)

Potential downsides

Still, educators and parents debate whether full-day kindergarten is worthwhile or makes no difference.

Lisa Fink, a parent and board president of Choice Academies charter schools, told the Arizona education board full-day kindergarten is a waste. She cited a 2014 study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy that concluded kindergarteners in Washington did not benefit from a daylong program, given its cost.

Children “need that play time. They need naps,” Fink said. “All-day kindergarten is a recurring fad, it is not the solution.”

Amy Torgerson, a mother of four, sent her two oldest children to a half-day kindergarten program and sent her third child to a full-day program at Sirrine. She says she doesn’t see a difference in the way they learned.

“I feel like full-day kindergarten gives the school more time to meet (state) standards with more children,” said Torgerson, who has no opinion on which program is better.

Parker has no doubts her full-day kindergarten students are capable of meeting academic standards.

“Five year olds can do much more than we really imagined they could before,” she said. “They’re little sponges. They’re minds are ready to go. They’re ready to gain the information.”