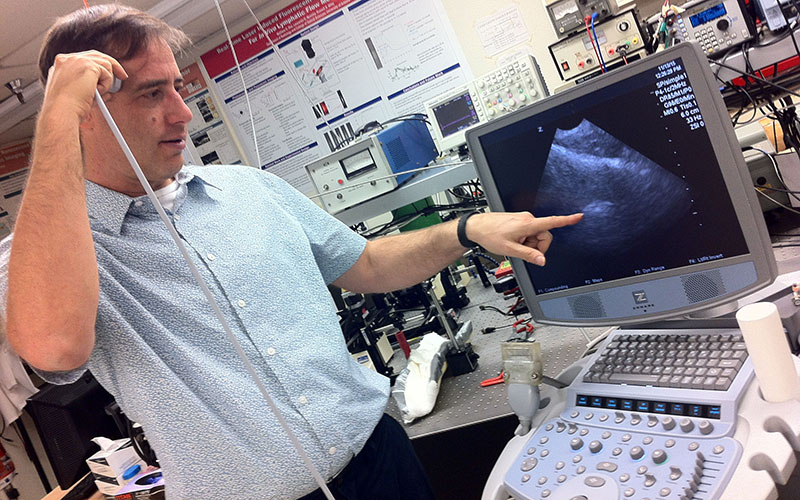

Russell Witte, an expert on ultrasound technology, hopes that his Acoustoelectric Brain Imaging prototype will one day be used in doctors’ offices to get a quick and clear image of brain activity. Human testing could be approved in as little as three years. (Photo courtesy of the University of Arizona)

PHOENIX – Medical professionals who study or work with the human brain have always struggled to get a glimpse at its inner workings.

There are more neurons and synapses in the brain than there are known stars in the universe. Neurology experts continue to map this complex biological computer as its 100 billion neurons and 100 trillion connections interact with each other.

Researchers at the University of Arizona may be on the cusp of a breakthrough when it comes to examining the deepest parts of the brain. A team of scientists and engineers is working on a technology, similar to an ultrasound, they believe has the potential to measure electrical activity deep inside the brain. They have dubbed the project, Acoustoelectric Brain Imaging, or ABI. The team will debut images captured by the technique for the first time at a conference in France next week.

ABI scanners could end up in doctors’ offices and research labs everywhere if the technique is as successful as the research team hopes. Production model ABI scanners could be compact and inexpensive to use, unlike large and costly MRI machines. The new technology could improve the accuracy of patient diagnoses and the effectiveness of follow-up treatment.

Assistant professor Russell Witte, an expert on ultrasound technology, serves as the project’s principal investigator. His ABI technique utilizes ultrasound waves, which pass through the skull where they interact with electrical and chemical pulses and provide measurements of the activity. The researchers can obtain the measurements without placing electrodes inside the patient’s skull.

Other noninvasive imaging techniques, like MRI, suffer from poor resolution and cannot penetrate as deep as ultrasound waves.

“We don’t have any non-invasive imaging techniques that can get down to any kind of detailed resolution that is close to the common behaviors that we have and the fast activities in the brain,” Witte said. “Although ABI may not be the ultimate solution, it is a much better possible solution than what is currently available.”

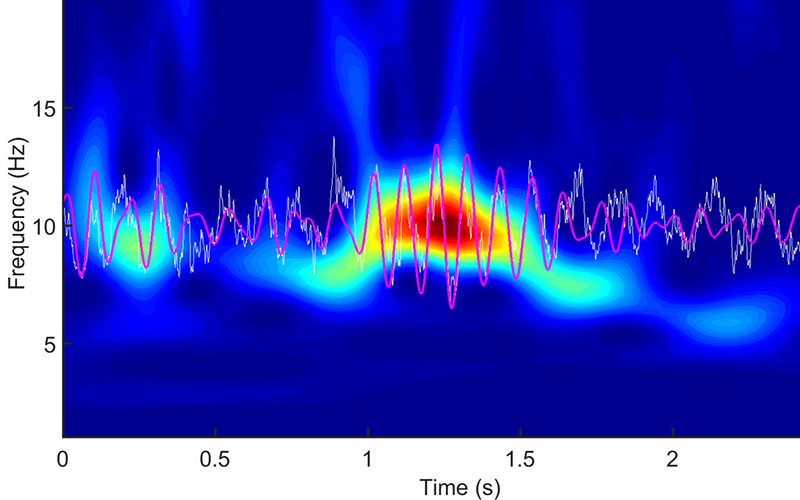

Acoustoelectric Brain Imaging will allow researchers to measure electrical activity in the brain, such as the brain waves that occur during sleep cycles. (Photo courtesy of the University of Arizona)

ABI technology can shed a clearer light on where abnormal brain activity originates and how those parts of the brain behave. Witte believes ABI will impact the treatment of a variety of medical conditions.

“There’s an unlimited number of applications, such as epilepsy, looking at depression and being able to recommend treatments. This technique could be helpful to visualize patterns within the brains on suffering individuals,” Witte said.

For example, ABI could help neurosurgeons identify areas of a patient’s brain responsible for epileptic seizures so they can remove them.

Stephen Cowen, an assistant professor of psychology at University of Arizona, believes ABI has much to offer the world of psychological research as well. Diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders can be difficult to get right because of their complex and overlapping nature. The extra resolution ABI produces may help psychologists better understand spectrum disorders such as schizophrenia and autism.

“If we can find out more accurately what brain systems are disorganized or not working properly, it may help us give a more precise diagnosis of that particular patient and the needs of that patient,” Cowen said.

Cowen also said doctors could use ABI to see if medications are working properly or causing negative side effects.

In its current phase of development, ABI has been tested on gelatin brain and skull mock-ups charged with electrical currents, and Witte said the results are promising so far. The research team is moving forward with plans to expand the study to include animal testing. The goal, of course, is to eventually put ABI machines in doctors’ offices.

Before they can move on to human testing, the project must gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval by demonstrating their prototype device is safe and that it has a real benefit in doctors’ offices. These types of approvals can take years, but Witte said he hopes they can piggyback on the reputation of ultrasound.

“I can see the first humans being tested three years from now,” Witte said.

It is too early to determine how much the technology would cost, he said.