After the Dallas police shootings, Deputy Susan Monroe said her daughter asked her to change careers, a request Monroe refused since she considers police work her “calling.” (Photo by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

MESA — When Susan Monroe, then a 32-year-old single mother, considered applying for a deputy position with the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, she spoke with her children about the risks.

“The one thing [my son] asked me was ‘What if you get shot?'” she said. “And I told him … it’s part of my job … one of those things that I may have to put myself between the good guy and the bad guy, or even between two bad guys.”

It’s a personal risk Monroe said officers take every day on the job to protect their communities, and she said it is one that members of the community might not truly understand.

Now, about 12 years after she went through the police academy, Monroe is participating in a new program called Police and Community Working Together to try to establish more personal relationships and understanding between individual deputies and families in the community.

The PACT program is a collaboration between the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, the Mesa Police Department and the Mesa Dr. Martin Luther King Celebration Committee, an organization that focuses on promoting peace and equality.

MCSO has four deputies who will participate in the PACT program, according to Paul Chagolla, deputy chief and bureau commander for the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office Support Services Bureau One and Community Outreach department. Assistant Chief Michael Soelberg of the Mesa Police Department said four to six of his officers are also expected to participate in the program.

Each officer will be paired with a family from the community for a month. Each week, the officer will spend up to three hours doing activities with that family, such as game nights or having dinner together. The participants will be able to submit suggestions for activities, and Angela Booker, 52, president of the Mesa MLK Committee, said Mesa MLK board members will decide which to approve to ensure the families and officers are comfortable with the suggested activity.

“In the MLK board, we were trying to figure out what we can do to help the community,” Booker said. “Where I grew up, we knew the police … we had a close community. And that’s what we need now.”

“When we developed the community outreach team,” Chagolla said, “it started with this idea of we wanted to show the community what we see in ourselves.”

Angela Booker said officers often have a “warrior” mentality, and said they need to move toward having more of a “guardian” mentality. (Photo by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

Deeper issues

While the Mesa Dr. Martin Luther King Celebration Committee seeks to use the PACT program to improve communication, negotiations to get the program going illustrate just how challenging that can be.

Formal meetings between officers and families have been delayed for almost a year, as the Mesa MLK board has been trying to work out language for program materials.

When Booker presented the PACT program to the Mesa Police Department, officers wanted Mesa MLK to change wording in materials about officer-involved shootings.

“They didn’t like us saying the number of people being killed [by officers],” Booker said. “They wanted us to narrow it down and say how many people were killed who were doing something illegal, how many people who were killed were just like in a police stop. And how many people who were killed that they’re still working on the cases.”

Soelberg said the language presented law enforcement in a negative light.

“When you talk about shootings, the officers can take offense to it. When you talk about murdering people,” Soelberg said, “obviously, there’s deadly use of force encounters, but those are use of force encounters that are unfortunate when they happen.”

“That’s why we took a little break to say, ‘Let’s reassess this. Let’s get some verbiage in there that it’s agreeable to both sides,'” he added.

Data about officer-involved shootings comes from many different sources.

According to a database created by The Washington Post, 990 people were “shot dead” by police in 2015, 42 of whom were in Arizona.

According to FBI data, 41 law enforcement officers were feloniously killed in the line of duty in the same year (2015) nationwide. The most recent data for Arizona states that three officers were “feloniously killed” in 2014.

In addition, the Gun Violence Archive data shows there were 79 officer-involved shootings in 2015 in Arizona. Forty of those incidents resulted in at least one death. Some of the incidents involved someone shot while engaged in a criminal activity. In many cases in the archive, information about specific circumstances is not available.

After months of delays, the PACT program is currently set to start this month with MCSO, and the Mesa Police Department is set to join at the end of this month or in early September.

Mesa MLK hopes to use donations and grants to cover the cost of the activities.

“We don’t want to put burden on the officer or the family to pay for it,” Booker said.

Chagolla said in an email that, while officers can volunteer in the program, they could receive compensation depending on the types of activities they complete.

Some officers and families have already met informally at some events, including a community forum.

Booker said Mesa MLK does not know of any programs like PACT, and the group wants more volunteers to apply for the program and to eventually take it nationwide.

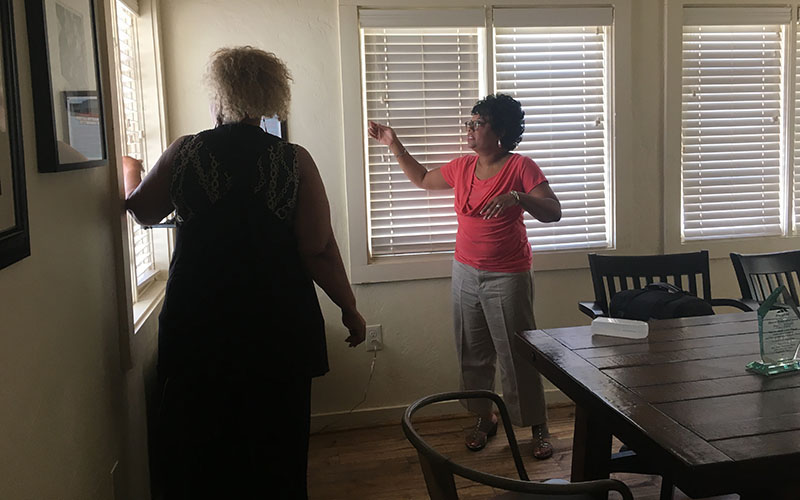

Ladina Willis (left) and Angela Booker of the Mesa MLK Committee joke around in the house of Mesa’s first practicing African-American doctor, which they currently lease from the city and hope to turn into a museum. (Photo by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

Soelberg said he and his team hope that the program participants can take what they learn and get others involved with this or other programs to further a relationship between police and the community.

“That’s just at the core of building that relationship: getting people involved,” Soelberg said. “Letting [civilians] know what to do and not to do, when to call, who to call when you need help.”

In addition to the PACT program, Monroe works with MCSO on other community projects, such as reading to children and giving books to teenage mothers to read to their children. According to Monroe and MCSO, reaching out to families and young people helps decrease their chances of being in the criminal justice system in the first place.

She added that even though they only work with one or two people at a time with community-interaction programs such as these, “you’ve got to start somewhere.”

Different cultures

One of the PACT goals is to help the officers and the participants, as well as others in the community, understand each other and appreciate how much they have in common.

To further an understanding, the program participants will be given questions to facilitate a conversation. They will write about their experiences in a journal to share at group meetings.

Booker said that, for some members of the community, especially people of color, being pulled over by a police officer can bring up many painful memories.

For her husband, she said it brings to mind childhood memories.

“At recess time, they played dodge ball,” Booker said, “and they would put him in the center and he was always the one they threw the balls at [because of his race].”

“When you’re coming up in an environment like that, and it’s constantly every day in your face, we want police to know all of that is inside of us,” she said.

That’s why she might get a little antsy or upset when an officer pulls up to her.

“It’s all those little steps from a child to being an adult,” she said.

Since Booker moved to Arizona in 2011, she said she’s been stopped four times by police officers.

“We had a policeman run our plates, follow us to our subdivision, and make sure that we actually lived there,” she said. “He waited until the garage door went up, then he sat there for a couple of minutes just to make sure it was our house.”

Ladina Willis, a 54-year-old volunteer board member with the Mesa MLK Celebration Committee, said you don’t always know the mindset of the civilian being pulled over.

“What if they just lost all their family members?” she said. “You never know the situation.”

Ladina Willis discusses some of the challenges she and Booker have faced while developing the PACT program. (Photo by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

Willis said she knows there’s an issue.

“I think that in part, for me, that you got to work on how to interact with different cultures and people,” Willis said.

She added that her daughter, who’s biracial and looks white, has been affected by the shootings of officers in Dallas and the high-profile shootings of unarmed black men across the country, and she has written about it on a blog.

“She said, ‘I never thought that I would say this, but it’s almost like you feel safe that your skin is white,'” Willis said. “And she was sad that she had to say that.”

Soelberg said his team wants to develop a relationship with both those who support the police department and those who have more negative perceptions of officers.

“We’re open to listening to everybody on both positive and negative,” he said, “because we have to build the relationships with both sides.”

Monroe echoed the idea of understanding others.

“I think there’s a lot of people that don’t wish any ill will on law enforcement, but I think there are some that are just angry at the system and angry at government overall,” Monroe said.

“We see people on the worst day of their life for the most part,” she said, starting to choke up. “When you’re holding that baby in your hands that dies, when you respond to a call from a child that got basically their head bit off by the family dog just by sitting and playing.”

Monroe said those are the kinds of experiences that many people in the community do not understand.

Another MCSO deputy, 38-year-old Hector Martinez, said officers must remember that the community is not all bad.

Deputy Hector Martinez of MCSO talks about the importance of “community policing” and not having what he calls the “cop mentality” of us versus them. (Photo by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

“We have to keep in mind…not [to] have that cop mentality that a lot of police officers have,” Martinez said, “the mentality of us versus them.”

“I think that’s where we need to start changing … stop looking at everybody as being something different,” Monroe said. “I look at it as everybody has something unique to offer.”

“We’re all the same,” she added. “We all bleed red.”

Related Story: Tempe students meet with police to dispel growing stereotypes

Arizona among highest states in nation for deaths by cops

Arizona among highest states in nation for deaths by cops New Phoenix police chief Jeri Williams: ‘Work tirelessly to make the community safe’

New Phoenix police chief Jeri Williams: ‘Work tirelessly to make the community safe’