Miranda rights, the right to remain silent in police custody and to have an attorney, are waived by people as much as 80 percent of the time, attorneys and experts say. (Photo by Keith Allison/Creative Commons)

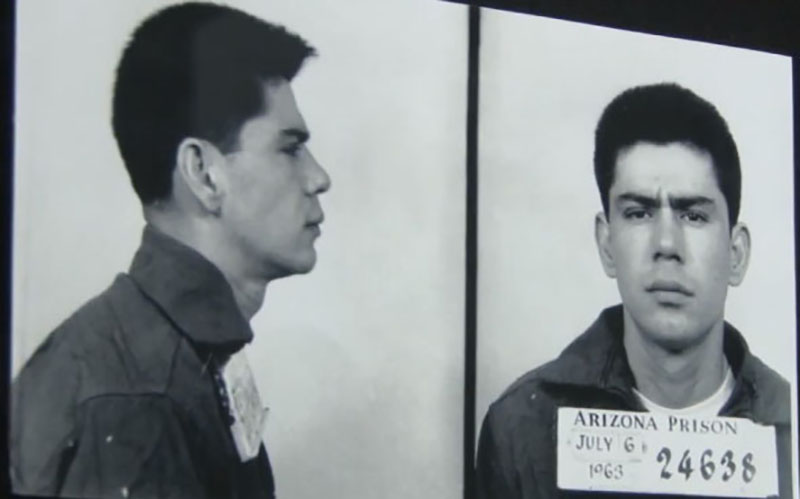

Phoenix police questioning of Ernesto Miranda on rape charges led to the Supreme Court’s 1966 decision requiring police to advise defendants of their rights – now known as a Miranda warning. (Photo courtesy the Phoenix Police Museum)

WASHINGTON – When Carlos Andres Maciel told police in Yuma County, before being advised of his Miranda rights, that he had broken into a church, officers were free to use that confession against him, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled late last month.

What Maciel did during that 2011 stop – talking to officers when he didn’t have to – is just one of the many ways that people give up their right against self-incrimination, said legal experts.

They said the well-known Miranda right, a case with its roots in Arizona more than 50 years ago, is still little understood by the public despite being a staple on police dramas and, as a result, it is waived in the vast majority of cases, knowingly or not.

“Research shows that many people do not understand their Miranda Rights fully, particularly juveniles, intellectually disabled individuals and those under high stress,” said Adam Shniderman, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Texas Christian University.

Shniderman was one of several academics and attorneys who estimate that people waive their Miranda rights as much as 80 percent of the time – or even more often, according to some experts. Reasons range from suspects who think they can talk themselves out of a situation to the misleading influence of TV shows, from language barriers to a fear of authority – even a belief in the power of the confessional.

Miranda warning

“You have the right to remain silent, anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With that in mind, would you like to speak with me?”

“It’s pretty easy to waive your rights,” said Jason Kreag, an associate professor of law at the University of Arizona. “You can do it implicitly or explicitly.”

Rights can be waived by speaking to investigators – as well as by not speaking.

“You have to tell police you want to remain silent,” said Tod Burke, a professor of criminal justice at Radford University and a former Maryland police officer.

At the same time, Shniderman said, “if you open your mouth and give them information you’ve waived your rights.”

The Miranda right was named for Ernesto Miranda, who was arrested in Phoenix in 1963 on suspicion of rape, kidnapping and robbery, and who gave a written confession after more than two hours of questioning by police. His attorney challenged the confession at trial and in 1966 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed that Miranda’s right against self-incrimination was violated because he had not been advised that he had the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney, and that any statements could be used against him in court.

Those “Miranda warning” phrases are familiar to anyone who has seen a police movie or TV show in the last 50 years.

Kreag said there were fears when the ruling came down that police investigations would be hobbled because no one would talk to officers anymore. But he said “Miranda hasn’t turned out to be a huge hurdle for law enforcement” in the intervening years.

“When I was a police officer, I don’t recall a case where someone said, ‘I’m not going to talk to you,'” said Burke. He said his interrogation technique was friendly and that in his experience, “people just want to talk, they become uncomfortable” with silence.

But Joseph Tully, a criminal defense attorney in California, said police are often to blame and that officers in an interrogation will ignore Miranda.

“Police more often than not will trick people into speaking, even when it’s not in their best interest,” Tully said. He said he has had clients complain to police that they asked for an attorney, only to have officers reply, “What do you need an attorney for, why don’t you just talk to me now?”

Tully said there’s “almost no teeth to Miranda anymore.” And Shniderman said “the Supreme Court has actually made invoking Miranda more difficult.”

Burke called Miranda rights as not clear-cut as depicted on TV dramas, which show suspects answering questions during police interrogations without lawyers present, and said it can be confusing for the average person. He said many of his college criminal justice students don’t understand custodial interrogation and they study it – so we can’t expect the public to understand it.

Vicky Hay, a Phoenix resident who said she worked at the law firm that handled the original Miranda case, said she is not surprised that most people waive their Miranda rights.

“Most people are not well educated, especially in Arizona,” Hay said of the law, in response to a Public Insight Network query.

Norm Pattis, a criminal defense lawyer and author in Connecticut, said another factor is people’s belief in the confessional. He said that many people think that if the officer understood their situation, they would be helped.

“It’s a normal instinct to want to explain yourself,” Pattis said, but typically you are only helping build a case against you.

Innocence also causes individuals to speak to police without attorneys present because “they feel they have nothing to hide,” Burke said.

But lawyers like Pattis encourage clients to resist that urge, saying it’s “no more wrong to refuse to talk to police than it is to refuse to jump off the highest building in town.”

Shniderman echoed that advice. “If you have a lawyer you’re going to be better off,” he said.

“Always be polite and respectful, but just say I want an attorney,” as soon as an officer says they need to talk to you, Tully said.

Once Miranda rights are waived, legal proceedings become an “uphill battle all the way,” said Tully. Shniderman said confessions are even harder to fight, as juries view them as the truth by default and “confessions are extremely persuasive.”

“The world is never made a better place when someone confesses,” Pattis said. “It just made an easier conviction.

“Criminal law isn’t about morals or right or wrong,” he said. “It’s about whether a state can prove whether you violated a law.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Sources in the Public Insight Network informed the reporting in this story through a partnership with the Cronkite PIN Bureau. To send us a story idea or learn more, click here.