WASHINGTON – Police departments in Phoenix, Mesa and Tucson fell short in a new report that rated departments for policies that ensure that body cameras are a “tool for accountability, not a tool for surveillance” by agencies.

The report released Tuesday by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights scored 50 major police departments that use body-worn cameras, on policies ranging from officer discretion in the use of the devices to who has access to footage recorded by them.

“There is an assumption that these cameras protect the civil rights and privacy of surveilled communities, but in cities nationwide that is simply not the case,” said Wade Henderson, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Departments studied ranged from those that have had high-profile use-of-force incidents, like Ferguson, Missouri, to those that have received at least $500,000 from the Justice Department for the cameras. They scored red, yellow or green for each policy they failed, partially met or met.

Phoenix received the lowest scores of the three Arizona departments in the report, not meeting criteria for its rules on availability of the policy, officer review of footage, footage retention, misuse, access and biometric use. The agency only partially met the standard for two categories: officer discretion and personal privacy policies.

“They got six red and two yellows and no greens, so I think hopefully this scorecard helps community advocates in Phoenix identify areas where the department policies could improve,” said Harlan Yu, a principal technologist at Upturn, the consulting firm that helped create the report.

Mesa didn’t fare much better, partially meeting the standard for officer discretion, personal privacy and footage misuse policies, but missing the mark entirely for the other five categories.

Tucson was closer to the middle of the pack, and the only Arizona police department to meet any standard. It met two – for policy availability and retention of footage – failed three and partially met three.

Phoenix police declined to comment on the report’s findings, while police in Mesa and Tucson did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

None of the 50 police departments scored fully met the standards in all eight categories.

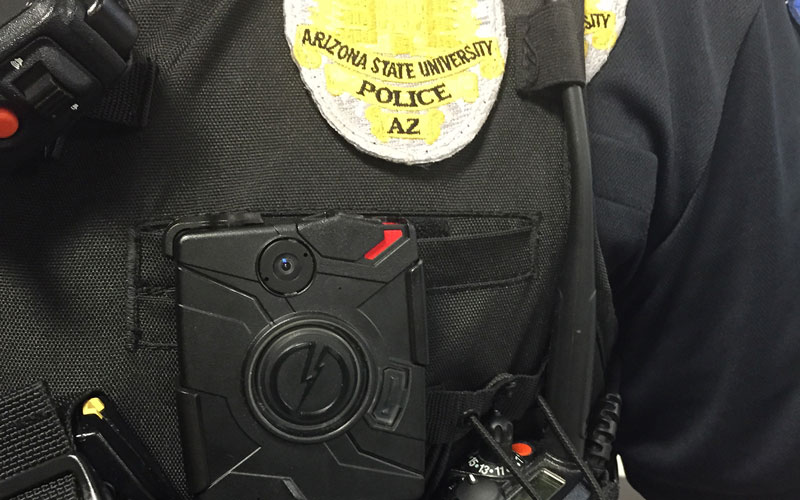

Body-worn cameras have been adopted by police departments across the country, especially where use-of-force incidents have gained national attention.

The Leadership Conference developed the report standards – the Civil Rights Principles on Body-Worn Cameras – in conjunction with civil rights, media and privacy groups from across the country. Only a few of the 50 agencies scored met the standard for policies regarding officer review of footage and regarding access to footage for people who were recorded.

Yu called that particularly concerning. Policies that allow officers to review footage before filing a report gives them a leg up when it comes to credibility in a courtroom, he said, while not allowing people to view the footage they were recorded makes it harder to make a case against officers who may have violated a suspect’s rights.

“Accountability is only possible if those who need to see the footage actually have access to it,” Yu said.

He added that while states have public records laws in place, most were passed before body-worn cameras began to be used in police departments – making it almost impossible for people who are recorded to view the footage.

“One of the most concerning trends that we’re seeing is that departments and state legislators are making it more difficult for the public to get access to footage of critical use-of-force incidents,” Yu said.