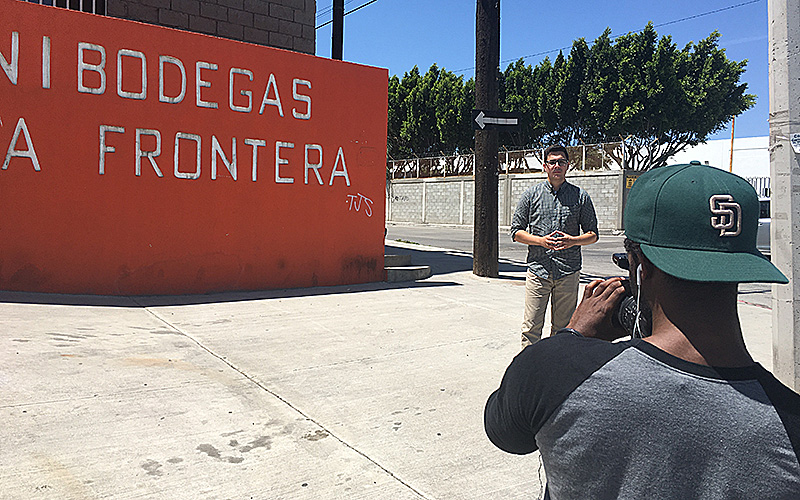

Mauricio Casillas and Cammeron Neely shoot a standup in Tijuana, Mexico during reporting along the U.S.-Mexico border. (Photo by Angela Kocherga/Cronkite News)

Editor’s Note: Recently, a group of Cronkite News reporters travelled along the U.S.-Mexico border to work on stories about the results of a Cronkite News-Univision News-Dallas Morning News border poll. Mauricio Casillas, a recent graduate of the Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University, was one of the reporters who contributed to our coverage. Here, he reflects on his experience as a Borderlands reporter.

Reporting on the border is unlike any other reporting I had ever done. The people, the culture, the issues — they are all unique. For instance, issues that people on the El Paso/Ciudad Juarez border face are not the same as those on the San Diego/Tijuana border. That’s why I think this kind of reporting is so important. Too often, we as journalists like to paint the entire border region with the same brush.

Yes, these are all border communities. Yes, there are similarities. But when you really go out and meet people and do the reporting, you realize how unique these areas truly are. What I found in my reporting is that border residents on both sides often don’t feel accurately represented by their own governments. Politicians in Washington and in Mexico City are arguing about border issues — but residents feel they are not understood. Mexico’s influence on the United States, and vice versa, cannot be understated.

Border and migration issues are at the forefront of the presidential election, and it is our duty as accurate and reliable journalists to go out and do some real reporting in the field After months of hard work reporting on three different border regions, I can tell you that these residents want a voice.

At the beginning of the Spring semester, I got to travel to El Paso and Ciudad Juarez. The community was gearing up for the arrival of Pope Francis. Juarez was a city that had dealt with incredible hardship because of the drug war. The pope’s visit symbolized a new beginning for the city. I had the chance to be on the streets of Juarez when the pope drove by. People — both young and old — had tears on their faces as the leader of the Catholic church passed by. In a lot of ways, the pope’s visit helped bring the communities of El Paso and Juarez closer together.

Later on, I traveled to the Nogales U.S./Mexico border. These are two cities that share the same name on different sides of the border. Their culture and economy are completely intertwined. During Holy Week, the lines to cross over to the United States were up to four hours long. People on both sides of the border heavily relied on crossing — it sustained their existence.

My final trip to the border was to the San Diego/Tijuana region. What fascinated me was how Tijuana’s professional soccer team brought both communities so close together. The Xolos, as they’re called, refer to themselves as “el equipo sin frontera” — the team without borders. Hundreds of American fans crossed over to Tijuana to enjoy games with the Mexican fans. Issues, stigmas and tensions were erased; instead the biggest problem facing this group of people was when the Xolos would score their next goal.

If I learned one thing from these trips, it’s that border culture is fascinating. It cannot be easily defined or generalized as American or Mexican. It’s a binational mix of both. I am incredibly thankful for the opportunities I had covering the border for Cronkite News. As a result of that experience, I am now a reporter at KVIA–TV, the ABC affiliate, in El Paso, Texas. I’m doing what I love. I’m continuing to cover the borderland.