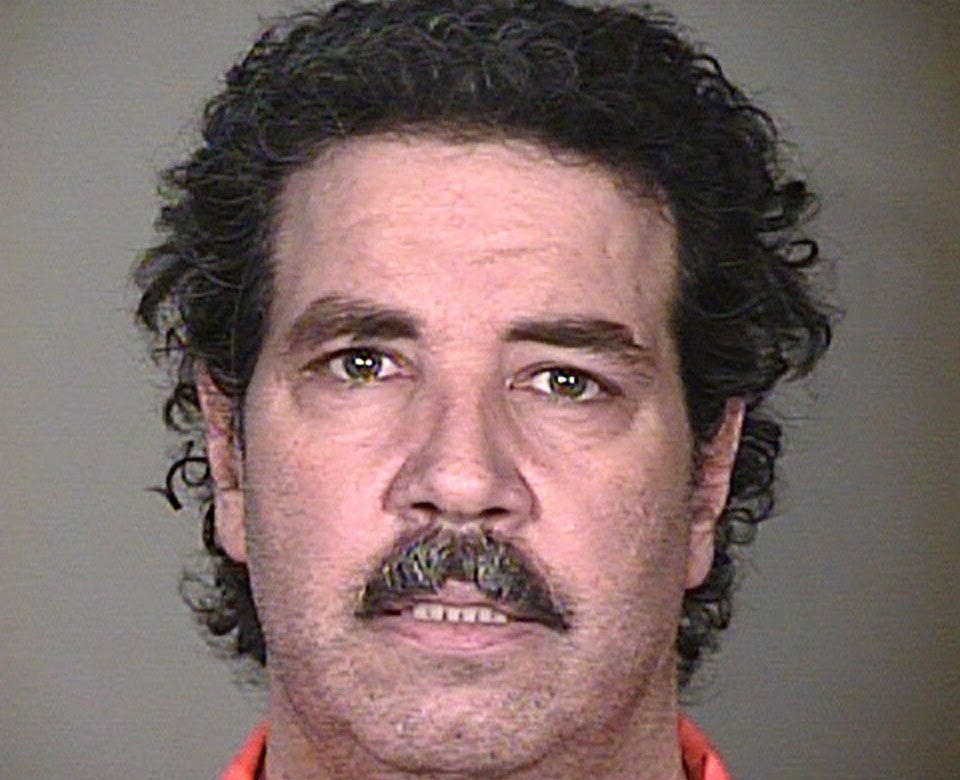

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned an Arizona Supreme Court ruling, which may give death row inmate Shawn Patrick Lynch another chance to challenge his death sentence in a 2001 murder. (Photo by Nathan O’Neal/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – An Arizona death row inmate could get another chance to challenge his sentence in a 2001 murder, after the U.S. Supreme Court Tuesday overturned a ruling by Arizona’s high court.

The federal court ruled 6-2 that Shawn Patrick Lynch should have been allowed to tell jurors he would not be eligible for parole if they chose not to sentence him to death for the killing of James Panzarella.

Tuesday’s decision reversed a 2015 ruling by the Arizona Supreme Court, which must now reconsider Lynch’s appeal in light of this opinion.

But in a dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, said the Arizona court had accurately told jurors about the sentences Lynch faced. He accused the majority of “a remarkably aggressive use of our power to review the states’ highest courts” in a case the the court decided without hearing oral arguments.

Attorneys for both the Arizona Attorney General’s Office and the Maricopa County Public Defender’s Office declined to comment on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling.

The case began on March 24, 2001, when Lynch and Michael Sehwani met Panzarella in a Scottsdale bar, according to the Thomas’ dissent.

Shawn Patrick Lynch is on Arizona’s death row for the 2001 robbery and murder of a man in Maricopa County. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections)

After the bar closed, they headed to Panzarella’s home, where Sehwani ordered a dancer from an adult entertainment service, ultimately paying her with checks from Panzarella, according to the Arizona Department of Corrections.

Once the dancer left, Lynch tied Panzarella to a chair and cut his throat with a knife, “nearly severing his head from his shoulders” in the process, according to Corrections’ Death Row Database.

Lynch and Sehwani made several purchases with Panzarella’s credit cards, including stays at motels where they rented adult movies, until police found them on March 26.

Sehwani pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and theft and was sentenced in 2008 to “natural life” – meaning he will remain in prison until he dies.

Arizona abolished parole for felonies committed after 1994. A life sentence under those rules is either natural life or life, which brings the possibility of release after 25 years if the governor grants clemency.

Lynch went to trial and was convicted in 2005 on charges of first-degree murder, kidnapping, armed robbery and burglary.

At sentencing, the prosecution argued that Lynch’s potential for danger in the future warranted the death penalty, according to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling.

Lynch’s attorney tried to argue that he was ineligible for parole and could not, therefore, pose a danger upon release.

But the judge in his case noted the possibility of release after 25 years, and denied Lynch’s request. The Arizona Supreme Court upheld that decision in the most recent of Lynch’s two appeals.

But the U.S. Supreme Court said that violated the precedent it set in a 1994 case, when it ruled that defendants must be allowed to tell jurors in death penalty cases if they are ineligible for parole.

Thomas disagreed, noting the jury instructions in Lynch’s case spelled out the difference between a death sentence, a “natural life” sentence and a sentence of life with the possibility of release after 25 years.

Assistant Arizona Federal Public Defender Dale Baich was not involved in this phase of Lynch’s case, but it is not the first case to arise out of Arizona’s 1994 Truth in Sentencing Act, which abolished parole for felons.

“This has been an ongoing issue in Arizona for the past 20 years,” Baich said.