SCOTTSDALE – A large orange and black butterfly glides through a flurry of multicolored wings to land on a bright pink flower. Soft music and a light mist fill the warm air in Butterfly Wonderland.

The monarch is safe inside the walls of the pavilion, but the reality outside is grim for a creature that is perhaps the most recognizable butterfly in America.

Global warming and pesticide use are disrupting the monarch’s migration patterns through Arizona and destroying its young’s food source, the milkweed.

The population of migrating monarchs has dropped by as much as 90 percent in two decades, according to Adriane Grimaldi, director of education at Butterfly Wonderland.

Now, butterfly advocates and the federal government are battling over whether the best way to protect monarchs is to put them on the endangered species list, even if that could mean halting research and stopping a generations-old practice of school children “raising” monarchs in science classrooms.

Amid the raised voices of debate, small solutions lie in the hands of any Arizona resident.

A multi-state trek marked by peril

Some butterfly advocates question whether the federal government should protect the monarch butterfly under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Migratory monarchs travel thousands of miles from Canada, some passing through Arizona, to California and Mexico each year, Grimaldi said.

The “migratory phenomenon” of the monarch butterfly is at greater risk of extinction than non-migratory monarchs, said Ronald Rutowski, an Arizona State University professor.

The difference in two decades is dramatic as scientists examine the throngs of orange and black butterflies that cluster on trees at the end of their journey. The population has dropped from an estimated one billion to as few as 33 million in 2013. Monarchs’ numbers have rebounded only slightly in recent years, according to Monarch Joint Venture.

Global warming, pesticide use and deforestation contributed to the decline.

Temperature tells monarchs when they need to travel, like a biological trigger setting them in flight. But in each of the last two years, monarchs delayed migration from Canada by six weeks because of warmer than normal temperatures. Without consistently cold temperatures, the butterflies’ instincts to move south weren’t triggered, Grimaldi said.

When the monarchs did start to migrate, it was too cold in the Midwest. Many monarchs died on their trip south, Grimaldi said.

Pesticides also have a major impact on the monarch butterfly population, Grimaldi said. An increased interest in growing corn for ethanol in Iowa has caused farmers to use pesticides to clear their fields that were formerly covered in the monarch’s host plant, the milkweed. That’s caused a more than 80 percent decline in habitat, she said.

“If we remove their host plant – that space where they lay their eggs – it is difficult for the population to expand,” said Gail Morris, coordinator for the Southwest Monarch Study, an Arizona-based advocacy group.

Deforestation in Mexico, where the butterflies spend the winter, has also hurt the migratory population, Grimaldi said.

Follow the blue dot: Scientists track migrating monarchs

Monarchs are as American as apple pie, baseball and reality shows. Children in hundreds of classrooms study caterpillars through their metamorphosis into butterflies.

Outside the classroom, professional and citizen scientists have studied monarch behavior for decades. Much is still unknown, but they are fascinated by what they have learned.

Monarchs are unique, the only butterfly that migrates in the U.S. It takes more than three generations of monarchs to trek more than 4,000 miles, through three continents, on their round trip, said Rutowski, the ASU professor.

During the trip to Mexico or California, monarchs are able to shut down many of their instincts, which allows them to live for up to nine months. It takes two more generations to make the return trip. Native monarchs like the ones that can be seen in Arizona year-round only live about a month, Morris said.

Monarch migration on the East coast is better known than the migration pattern in the West, Rutowski said. The Southwest Monarch Study has attempted to dispel uncertainty through a monarch-tagging program.

After capturing the butterfly with a net or picking it up while the insect is feeding, citizen scientists place a pencil-eraser sized blue, numbered tag on the monarch’s wing. The migration pattern of the tagged butterfly can be recorded if the butterfly is observed again, said Morris, who coordinates the study.

The tagging program has helped to track monarch migration through Arizona, said Morris, who has tagged more than 500 monarchs.

The Desert Botanical Gardens have not yet had a monarch sighting, but the butterflies will soon flutter through Arizona as part of the northward spring migration, said Kim Pegram, insect ecologist at the botanical gardens in Phoenix. The butterflies begin to leave their winter locations as early as the middle of March.

How monarchs help bring food to the people’s tables

Butterflies are more than winged beauties. They forecast environmental and human health.

Monarch butterflies are an “indicator of the health of our pollinators,” Morris said.

Pollinators like bees, flies, beetles and butterflies are necessary because they help put food like oranges, berries and butter on people’s tables. The decline of monarch butterfly populations often signals the decline of other pollinator populations in the area, Morris said.

“Oftentimes, we’ll see that all of them are declining at the same time, which indicates something major in the habitat,” Morris said.

If monarchs become protected under the Endangered Species Act they will join the ranks of the Mexican wolf, Bald Eagle and American Burying Beetle.

Battling over what’s best for monarchs’ survival

Even people who have made monarchs their life passion battle over whether to include them on the endangered species list, because that could signal the end of some conservation efforts by citizen scientists in Arizona and across the country.

The Center for Biological Diversity and the Center for Food Safety issued a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in January. According to the notice, the federal agency failed to determine if the monarch should be protected under the Endangered Species Act during a yearlong deadline for official response.

The U.S. agency’s initial 90-day review of the organization’s’ petition to list the monarch as endangered or threatened under the act concluded that “the petition presents substantial scientific and commercial information indicating that listing may be warranted for the monarch butterfly.” Still, the agency has not decided to include monarchs on its endangered species list. The agency did not return phone or email requests for comment.

Grimaldi would prefer to see the iconic butterfly on the less-onerous threatened species list.

“If they’re endangered, we can’t touch them and we can’t tag them,” Grimaldi said.

When a species like the monarch butterfly is listed as “endangered,”

the federal government gains the authority and funding to protect the animal and its habitat, according to the fish and wildlife agency. This means that all conservation efforts would be regulated by the government.

However, the act also restricts “taking, transporting or selling the species.” The act not only could prevent groups like the Southwest monarch organization from tagging the butterflies, it could also prohibit schools across the country from raising monarchs in the classroom for release in the wild, Grimaldi said.

“Just like any other endangered species, you can’t touch them. They’re hands off,” Grimaldi said. “That could cause a problem with the monarchs where people who want to help won’t be able to…then the numbers aren’t being helped that way.”

A provision may be added to the endangered designation that would allow educational groups to continue to tag a limited number of monarch butterflies, Grimaldi said.

Arizona teacher Adrianna Tinguey has raised monarchs with her second-grade students at the Odyssey Preparatory Academy for several years. However, for the last two years, monarch caterpillars have been replaced by the Painted Lady species, who don’t need milkweed to thrive.

“They name them,” Tinguey said. “It is kind of sad when we let them go.”

Building nectar highways for monarchs to navigate

While the endangered designation remains in limbo, experts and citizen scientists across Arizona are making efforts to conserve the monarch butterfly through research and coordinating “monarch way stations.”

The monarch way station at the botanical gardens provide native and migrating monarchs with nectar plants for nourishment and milkweed for female monarchs to lay eggs, said Kim Pegram, insect ecologist at the gardens in Phoenix.

A monarch waystation requires nectar and milkweed plants, shelter from the sun and a ban on pesticide use.

Similar projects to provide monarchs with habitat are happening throughout Arizona. The Southwest Monarch Study partners with organizations to plant more than 2,000 milkweeds in the right locations, Morris said.

Sunflowers, thistle and rabbit brush are just a few flowers that help create a “monarch nectar highway” as butterflies migrate across the state, Morris said.

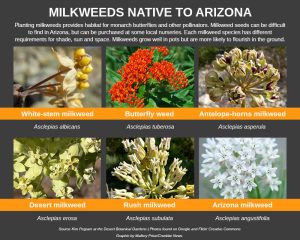

Planting a butterfly garden with milkweeds and nectar-rich flowers is a good way for people to help monarch butterflies and other pollinators, Pegram said. The Desert Botanical Gardens recommends six native milkweed species. The plants are difficult to find but easy to grow, she said.

Anyone interested in learning more about growing butterfly gardens or monarch conservation can learn more at the Desert Botanical Gardens or Butterfly Wonderland. Additional information about tagging butterflies can be found on the Southwest Monarch Study website and milkweeds can be purchased at several nurseries in the area.