PHOENIX – A small white plastic box is lowered into one of the seven graves made the day before. Fifteen prisoners look down into the hole much too large for the tiny infant box it contains.

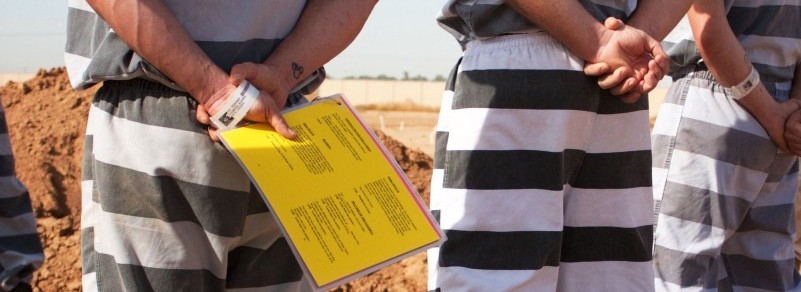

The group of prisoners, known as the chain gang, is linked not only by the chains on their dusty black boots, but the weight of burying the county’s indigent. It falls to them to put to rest the destitute with no financial means to make arrangements for their burial.

“We use different resources to find out if there are funds out there or if there’s maybe real estate or some other sort of asset that could be used for this person’s final arrangement before we use the county’s taxpayer dollars,” said Ramon Franco, the indigent burial coordinator for Maricopa County’s Public Fiduciary Office.

The Public Fiduciary’s Office reviews requests for indigent burials, including applications from the families of the dead, to determine whether these final arrangements can be made. The county contracts with a funeral home to assist with these services through the indigent burial program.

“So we try to make sure that we are the last possible resource that is being used for that,” Franco said.

Since July 1, 2015, the Public Fiduciary’s Office has received a total of 465 applications for indigent burials, with 301 of them being approved.

Those not approved are deemed to have the financial means to pay for the costs.

In cutting costs, prisoners from Tent City, Estrella and Towers Jails bury about six bodies every Thursday morning, as part of the Last Chance rehabilitation program. Inmates volunteer to be a part of the 30-day program to get out of lockdown and back into general population after receiving a minor offense.

“Everyone is short of funds,” said Sgt. Deana Lopez, who started overseeing the work of the chain gang about a year ago. Lopez believes the inmates’ work creates a partnership with the community.

To date, there have been more than 5,300 indigent burials in the White Tank Mountains by the chain gang. The identity of the dead and the circumstances surrounding their death often remain unknown.

Adam Pinon, contract compliance inspector for Maricopa County, helps to oversee the maintenance of the cemetery.

“The most touching thing to me is the volunteers. I get paid to be there, it’s part of my job,” Pinon said. “The volunteers make sure that nobody is laid to rest alone. They don’t have to do that.”

Volunteers like Louisa Milstead, her white laundry basket holding fake flowers and laminated psalms, help give strangers a ‘proper’ burial.

As the prisoners walk from one grave to the next, the chains around their ankles drag on the ground, picking up a mask of dust that blurs their feet.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven,” a prisoner begins reading Matthew 5:3 over the grave.

The men stand in silence until the last burial of the morning.

“Thank you very much gentleman, this is not an easy thing to do. This is probably the hardest thing you’ll ever have to do. I don’t know why any of you were here and I don’t care why any of you were here,” Milstead said. “Keep them in your heart. God bless you all.”

Milstead is a sister at a church in downtown Phoenix, but on a normal Thursday at White Tanks Cemetery, Milstead would not be alone. A priest or officiate would assist in the allotted fifteen minutes to mourn.

The babies outnumbered the adult burials, another oddity.

White plastic pipes emerge like wildflowers across the desolate horizon. They are placeholders for tarnish resistant brass disks that will mark their name, birthday and place of rest.

But not all graves will be marked with names.

So far this year, there have been five bodies marked as unidentified in the White Tank Mountains.

Before White Tanks Cemetery opened in 1994, the Jane and John Doe’s were buried in Twin Buttes Cemetery in Tempe. Twin Buttes opened in 1950 and contains over 5,000 graves.

Todd Matthews is the director of communications and case management for the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs).

In an effort to prevent the burial of unidentified bodies, Matthews has spent most of his career creating profiles to match the characteristics of a missing person to an unidentified individual.

Before they go to the White Tanks Cemetery, it falls to him and others to find out who they are. Not an easy feat, since 306 bodies remain in Maricopa County’s Unidentified Persons Bureau.

“I was essentially the first cyber sleuth,” Matthews said. For 10 years, he attempted to find the identity of a Jane Doe and ultimately did, using the Internet in 1998.

About nine years later, a group of professionals, medical examiners and law enforcement authorities approached Matthews to contribute to the development of NamUS, a national database that uses chronological, geographical and physical characteristics to match a missing person with unidentified remains.

NamUs stores records, fingerprints and DNA while working with investigative agencies and the public to identify missing persons.

Arizona has more sets of unidentified remains and, per capita, missing persons cases than almost any other state, according to NamUs.

Dustin Driscoll is the Regional System Administrator for the NamUs Southwest region, including Arizona, California, Hawaii and Nevada.

“Arizona is second under California for the most unidentified cases in the system. We literally are at exactly 1400 right now,” Driscoll said.

The National Institute of Justice created the Identify the Missing Project in 2010 and awarded a grant to the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s office that same year.

Rachel Murguia, who works at the Maricopa County Public Fiduciary, worked with Christen Eggers from the Medical Examiner’s office to look for grave markers in the Twin Buttes Cemetery and exhume bodies in order to identify remains with forensic technology.

Thirteen individuals have been identified through the project and although the grant ended in 2013, there is still a possibility that others will be identified.

“Now we work on them on a case by case basis,” Murguia said.

However, most cases the Public Fiduciary Office reviews are individuals whose identities are known but no money is available to bury them.

Every indigent burial costs $350, which includes cremation or burial.

Next Thursday, another 15 prisoners will fill the newest graves with the weight of a small box.