A trumpet mute sits on a stand waiting prior to the beginning of the Chinto Mendoza Jazz Festival.(Photo by Cammeron Neely/Cronkite News)

Jacinto “Chinto” Mendoza performs at the 10th annual Chinto Mendoza Jazz Festival at the CEART Tijuana arts center in TIjuana, Baja California.(Photo by Cammeron Neely/Cronkite News).

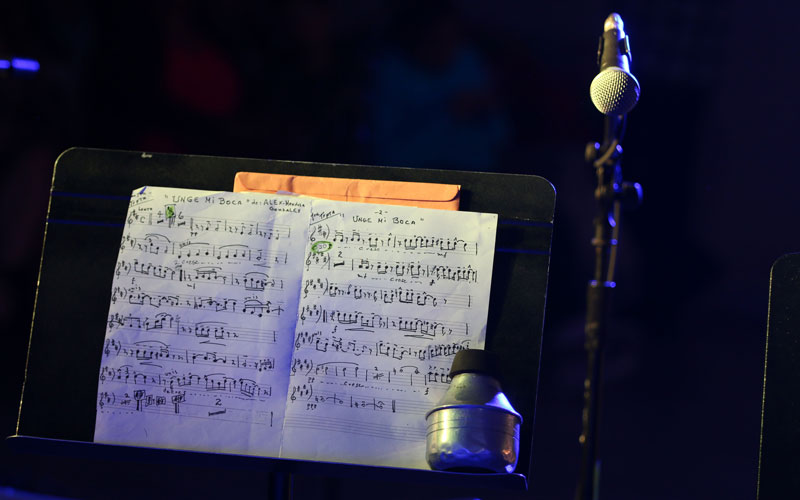

Álex Mendoza sings during his father’s Chinto Mendoza Jazz Festival.(Photo by Cammeron Neely/Cronkite News)

Jacinto “Chinto” Mendoza conducts during the Chinto Mendoza Jazz Festival.(Photo by Cammeron Neely/Cronkite News)

TIJUANA — Jacinto “Chinto” Mendoza’s first instrument was the violin. He was just 5 years old. A couple of years later, he adopted his signature instrument, the alto saxophone.

Mendoza is now 79 and one of Baja California’s most storied jazz musicians, so revered the state organizes an annual jazz festival in his name. A native of Mexicali, a border city and the capital of Baja California, his life is the embodiment of a mixture of global influences, an example of how music knows no borders.

“If you like music, you can’t do anything about it,” Mendoza said in Tijuana last Friday. “You are transmitting all that you feel to the people, and you can make the people feel good.”

Mendoza and his music have lived through Baja California’s transformation from a state associated with violence to a region with a modern and intricate culture. Tijuana in particular stands in a different light than it did when it was a notorious sector for drug and human trafficking into the U.S. Cartel violence in the region peaked in 2008, with 844 reported homicides.

Even as violence in Tijuana appears to be on the rise again, entertainment and dining ventures have been fundamental in drawing both American and Mexican tourists back to the city with popular concerts and critically acclaimed restaurants.

The distinctiveness of Mendoza’s life is celebrated by the Chinto Mendoza Jazz Festival, held last weekend in Baja. This is the 10th year of the festival, organized by Baja California Cultural Institute to honor his lengthy contribution to the region’s music scene.

“I’ve dedicated my life to try and introduce myself to the elements of music as much as I can,” Mendoza said.

The festival includes performances by various jazz groups scheduled throughout Baja in locations including Ensenada, Tecate and Mexicali. The Tijuana shows take place in CEART Tijuana, a state arts center looking to elevate the profile of regional art and music.

“Our intention is to convert CEART into the home of Mexican jazz,” said Adai Villarreal, the center’s assistant to the director. “There is an important jazz movement here in Tijuana.”

Mendoza has been recognized throughout Mexico for his musical career. As a child, he played Mexican folk with regional musicians. He moved to Mexico City in the ‘50s, playing alongside Latin figures like Celia Cruz and Alberto Vázquez. He later studied classical harmony at the University of Chicago.

Mendoza — with an astute sense of humor and seemingly always in motion — speaks about jazz in a way only someone who has lived and studied it for decades can. He classifies the genre as a math or a science, breaking it down to variations of scales, progressions and famous melodies. You can hear this in his lines as he improvises.

It’s that science, he said, that helps make music a global language. As such, it goes beyond the physical barriers between Mexico and the United States.

“We were always working together with music,” Mendoza said before his Tijuana show, outside his hotel room, wearing a checkered vest and a puffy turquoise shirt. “Rhythm is a universal way of thinking about music.” In previous years, he collaborated with American artists from Boston, Los Angeles and New York City.

Other genres of Mexican origin, such as rancheros and mariachi music, also transcend borders, he said. Mendoza and his children — son Álex and daughter Chikis — want to use the festival as a chance to show how jazz can bring Mexico together. Mendoza’s band, “Proyecto Frenesí,” played their final festival show last Saturday in Mexicali, his home.

“It’s not just Tijuana,” Chikis said. “Primordially, it’s all across the border. The need to improvise, over established melodies or in ones you will compose, is what drives jazz. It’s a necessity of expression.”

That Friday night, the crowd quickly packed CEART Tijuana’s international gallery, which had an exhibition of trunks featuring the cultures of different states and cities in Mexico.

Mendoza led Proyecto Frenesí through relaxed jazz arrangements of songs known in Mexico and the U.S. Álex sang the first stretch — standards like “Bésame Mucho” and “Feeling Good” — with a voice that extended past the gallery’s walls. Chikis then joined for a performance of “Mexicali Rose” and a tribute to singer Natalie Cole, whose final album was in Spanish and inspired the band’s name.

In front of the festival audience, Mendoza bounces and jerks, the rhythm of his band exhaling from his body. His solo lines aren’t as long as those from the younger players, but they’re loaded with passion and ideas. It’s not out of place to wonder why he even needs a microphone.