Phoenix artist Thomas “Breeze” Marcus painted a mural at the developing arts complex The Container Yard he visited Los Angeles in late January.

(Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

Street art has picked up popularity in downtown Phoenix. This alleyway at Fifth and Roosevelt streets has brought together work from many different Phoenix artists.

(Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

A developing art complex in Los Angeles, The Container Yard, features murals by various artists curated by artist Vyal One. Thomas “Breeze” Marcus, whose mural is on the right, is a Phoenix artist who visited Los Angeles in late January. (Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

Phoenix muralist Angel Diaz stands in front of a skull he painted at Fourth and Roosevelt streets as part of a large mural with several other Phoenix artists. Diaz often travels to Los Angeles to paint. (Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

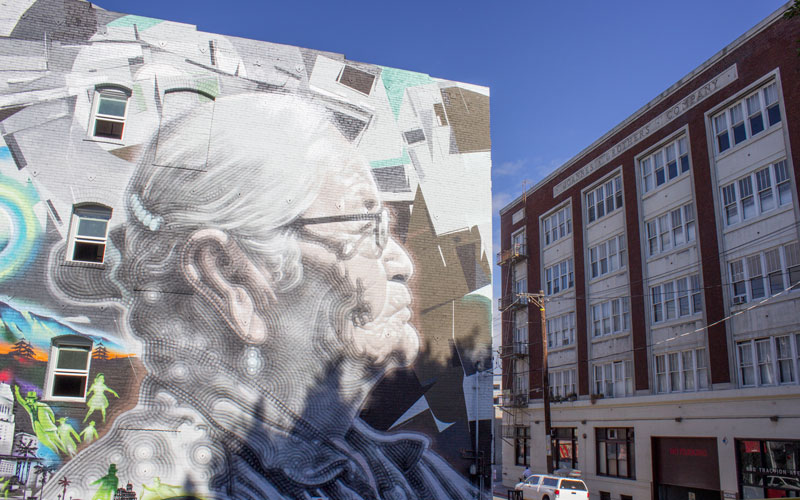

Artist El Mac has painted murals across the world. Based in Los Angeles, El Mac recently painted a mural at the new Cobra Arcade in Phoenix.

(Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

Phoenix muralists Angel Diaz and Thomas “Breeze” Marcus have worked on pieces throughout downtown Phoenix, including the area around the intersection of Fifth and Roosevelt streets. Both artists travel to Los Angeles often to paint. (Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

Artist El Mac has painted murals across the world. Based in Los Angeles, El Mac recently painted a mural at the new Cobra Arcade in Phoenix.

(Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

Los Angeles-based artist SART has traveled to Phoenix several times to work on murals. He plans to return again in March for Paint Phx street art festival.

(Photo by Molly Bilker/Cronkite News)

LOS ANGELES — When Los Angeles street art photographer Eriberto Oriol and his wife, Angelica Gonzalez-Oriol, traveled through Arizona, they’ve noticed a trend: Street art in Arizona feels more progressive and meaningful than much of the work they see in LA.

“The artwork there, it grabs me because I feel it has substance. It’s related to the everyday life that people are going through,” Oriol said. “I, always, when I go back there, try to bring something back from there to post, whether it be a landscape thing or some other artwork that I see there, because I feel that LA needs to see it.”

Muralists in Phoenix, meanwhile, have been visiting LA to paint its walls. This exchange offers a surprising conclusion for some experts: Though a less established scene, Phoenix street art may have a lesson or two to teach LA.

The artwork is a reflection of Arizona’s reality faced by immigrants and Native Americans, with issues ranging from Senate Bill 1070 to fighting stereotypes, say experts like Joel Garcia, director of programs and operations at LA community arts center Self Help Graphics and Art.“Because of the (political) climate, how it’s been the last 10 years or a little bit more than that, it definitely pushes the creative folks to be definitely rooted in that struggle, versus here it’s just art for art’s sake,” Garcia said. “It just seems like artists are willing to fight more for their spaces and also be more committed to shaping their communities.”

Just six hours west of Phoenix on Interstate 10, Los Angeles has been a center of street art culture since the 1960s Chicano mural movement. Its arts district is 40 square blocks of the 503-square-mile city.

Today, Phoenix muralists like Angel Diaz, Thomas “Breeze” Marcus and Douglas Miles are bringing their work to LA. In late January, Diaz worked on a portrait commemorating recently deceased rapper Cadalack Ron, and Breeze painted a mural at developing art complex The Container Yard.

These artists have been traveling to LA for several years. In 2013, Breeze and Miles worked on the What Tribe Project, an exhibit combating stereotypes of Native Americans in the media that was curated by Miles, who is an Apache from San Carlos.

The exhibition was hosted by Self Help Graphics and Art, where Breeze, Miles, New York artist Renelle White Buffalo and LA muralist Vyal One painted a mural on one wall. It since been painted over.

Garcia, who worked with Miles and Breeze for the What Tribe Project, has visited Arizona for events such as workshops on community engagement using art in response to SB 1070. Garcia noted other areas where he felt Phoenix was outdoing LA.

“Phoenix has been at least a little more creative when it comes to placemaking strategies than LA has. Or, they’ve done it in a way that incorporates the immediate community in the entire process,” he said. “In LA, people kind of tend to roll them out as in the way they think works best without really working with community or having them be part of the planning process from the start.”

In return, Garcia said, LA artists can help Phoenicians by providing opportunities for capacity building. Merchandising artwork and teaching workshops — part of Vyal One’s work — are a couple examples.

“I think for artists here in LA, since there is so much competition, you have to be a little bit more diverse,” Garcia said. “You can’t just focus on one medium.”

While artists like Oriol and Garcia see progress in Phoenix they feel is lacking in LA, Phoenix street artist Angel Diaz has been hoping to move to LA, where he feels there’s a better place for his work.

“It’s a way bigger state, with more cities. It just feels unlimited,” Diaz said. “Phoenix, it’s big, but they’re not all up on graffiti art. They’re not hip to everywhere being painted. So it’s kind of like I always hit dead ends.”

Miles is focused less on the differences. Coming together, he said, street artists may exchange cultures and regional styles, but at heart they’re finding what’s shared.

“We’re not really looking at what are the differences, we’re actually looking for the similarities,” Miles said. “Like, ‘Oh, here’s a guy from the Apache reservation, but he loves art as much as I do.'”

On a larger scale, this muralist migration provides the opportunity to create a worldwide arts community, said Cindy Schwarzstein, founder of Cartwheel Art, which includes a magazine and tours of the downtown LA arts district.

“It’s creating this incredible collaborative global experience for us all,” she said.

Street art is important, Los Angeles muralist Damon Martin said, because it raises the perceived value of neighborhoods and raises awareness of sociopolitical issues. Martin’s downtown LA mural of three elephants is meant to bring attention to the illegal trade of ivory tusks.

That kind of social awareness is part of what Oriol, Gonzalez-Oriol and Garcia have expressed that they’re seeing more often in the street art from Arizona. Art that engages with community issues and realistically reflects the natural environment.

“To me, Arizona — Tucson and Phoenix — are leaders in the art scene, because they’re seeing what Los Angeles still is slow to recognize,” Gonzalez-Oriol said. “I have to congratulate Arizona, to tell you the truth. Because they are seeing the essence of art.”