Brunson-Lee fourth-grade teacher Rachael DeFraesart leads her students in reading lessons and encourages their success. (Photo by Hillary Davis/Cronkite News)

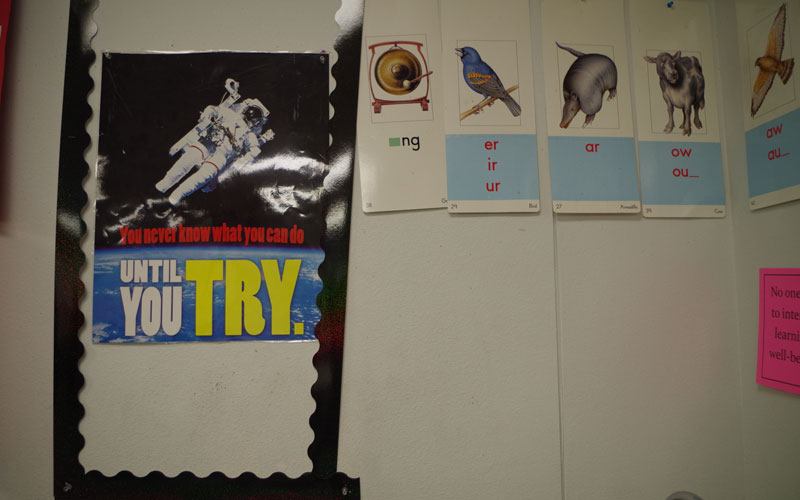

Rachael DeFraesart’s classroom is filled with signs of encouragement. She believes college should be a goal. (Photo by Hillary Davis/Cronkite News)

Rachael DeFraesart has been at Brunson-Lee for six years, all but one of those teaching fourth grade. (Photo by Hillary Davis/Cronkite News)

Rachael DeFraesart’s Room 122 is full of all the fourth grade trappings: Posters that diagram long multiplication and illustrate phonics, define vocabulary words and offer inspiration.

And then there are the pops of Grand Canyon University purple, the color of DeFraesart’s alma mater. She puts a pennant on the wall, a coffee mug on the filing cabinet and a balloon in the hall by her door as everyday reminders to her students that college is achievable.

On the way, they will refine their reading, like they’re doing on this morning in their Brunson-Lee Elementary School classroom. It’s coming up on 9 a.m. on a Wednesday and about 20 children hunch over their books, fingers tracking words on the page and eyes taking in the words.

Reading is a pivotal bridge to cross at Brunson-Lee, a school where 60 percent of its children live in poverty and almost all of them are Latino. But if they’re like their schoolmates over the last several years, they will move forward on measurable objectives, covering more ground than might be expected in a central Phoenix school where the majority of students come from working poor families.

On first glance, the school is merely living up to the dubious expectations of an inner-city school. Only about two-thirds of its students can read at grade level. Less than that can do grade-level math.

Yet Brunson-Lee is doing something right. Its students are making moderate but significant achievements.

The socioeconomic challenges at Brunson-Lee are similar to its sister schools in the five-school district bounded roughly by Thomas Road and Washington Street to the north and south, and 36th and 56th streets to the west and east.

Its gains are generally reflected in the other schools, too: Balsz Elementary made small but measurable progress on standardized tests. Crockett Elementary did a little better yet.

But Brunson-Lee, located at 1350 N. 48th St., was a clear leader, improving its overall math pass rates by 13 percentage points, and its reading pass rates by 17 points, according to statistics from the Arizona Department of Education. Among the highest-poverty school districts clustered in Phoenix’s central core, few schools could top that growth.

Five years ago, less than half of these children could meet math or reading expectations. The Arizona Department of Education labeled Brunson-Lee a “Focus” school — a somewhat euphemistic way of saying that Brunson-Lee is a low-income school that is “contributing to the achievement gap in Arizona.”

The state flags schools in the bottom 25 percent, with the lowest-achieving students at that school showing a lack of progress, or with a significant difference between the lower and higher achievement pupils passing state standardized tests. Last year, Brunson-Lee was one of 68 schools in “Focus” status.

But over that time its test scores have inched forward.

District administrators added an extra month to the school year throughout the district – an attempt to beat the slide some kids take during the summer.

Superintendent Jeff Smith, who took the helm in 2009, had the principals share solutions rather than try to solve problems their own way, and moved professional development to Wednesday afternoons rather than on weekends. Teachers in the same grade levels also send their classes to music, art, library or physical education sessions at the same time every day so they can have a common planning time to discuss similar lessons.

As Brunson-Lee’s curriculum coach – every school in the Balsz district has at least one – Sarah Revell guides the teachers. She said research shows that building professional communities and scheduling ongoing, workday-embedded training has better outcomes.

Two years ago, the teachers started unpacking the new Common Core-aligned standards, starting with the third grade, the first year of high-stakes testing. Through planning, observation and debriefings, they identify challenges.

“I feel like it’s a long-term process,” she said. “It’s not something you’d see instant gains from.”

Principal Ryan LoMonaco said getting out of “Focus” school status can be hard because it doesn’t take into account growth. Instead, it’s an annual snapshot. The ranking does, however, come with added funding for student improvement, allowing Brunson-Lee to purchase the flash cards it sends home with parents or pay for small-group tutoring.

He said that transiency is one of the school’s challenges. Most of the homes within Brunson-Lee’s boundaries are rentals, and without the roots of ownership, some families stay for just one lease. Only about half of his sixth graders were there for kindergarten.

Many older children look after younger siblings while parents work nights.

And as Common Core standards are still new, districts may vary in their approaches – and with the cumulative structure, building on what was taught in the years prior, transferring can be confusing for pupils who have to learn the Balsz way.

Add to that the complex pedagogy of Common Core that has many parents struggling to understand themselves.

“That’s the parents that are home,” LoMonaco said. “If you have a family member that’s working at night, it’s even tougher for kids to get that help.”

Still, he says, parents are the lifelines. Teachers seize opportunities to have parents supplement learning at home where they can, presenting the drills as games.

Parent-teacher conferences have been recast as meetings of Academic Parent Teacher Teams, where instead of just reading a report card, teachers tell parents where their child is relative to the rest of the class and to the end-of-year goal, and give them an activity to take home, whether remedial or advanced.

“It’s really putting the ‘what’ and ‘how’ to helping students at home,” LoMonaco said.

Revell said parents have responded positively to the new dynamic. Instead of simply being told what’s happening, she said parents feel engaged.

“It feels very empowering to parents, and they feel a lot more informed,” she said.

Teacher turnover is also high. Revell said pay is comparable to nearby districts, but about half the staff leaves every year, either for retirement, or to move out of the area, or because they’ve finished their two-year Teach for America obligation.

Most of the teachers have less than three years’ experience. But those who are on staff are reflective and dedicated, she said.

Now in her sixth year, Rachael DeFraesart is one of the relative veterans. When she graduated from Grand Canyon University, she committed to a program that required at least three years in a local low-income school. She had never heard of the Balsz School District because it’s so small.

She has been at Brunson-Lee since, all but one of those years teaching the fourth grade.

She said the district’s teacher-training support kept her here. The children are eager, and the parents connect with the school if meeting times are flexible.

“Our parents are very supportive and you can tell they try really, really hard to be here when they can,” she said.

DeFraesart said the student transiency has stabilized some over the last couple of years, possibly in line with the improving economy. But even when families do move out of Balsz’ boundaries, some keep their kids at Brunson-Lee.

“I think that says a lot.”

LoMonaco said one of his objectives is to get students to believe in their own ability to challenge themselves. It can be academic. It can be behavioral. One boy, for example, has a hard time sitting still in class.

So he honed in on something the boy likes and struck a deal: three days of no disruptions in class, and the boy would earn a friendly game of basketball with the principal and a friend.

He buckled down and reached the goal.

“To have that kid be successful for three days in a row to earn all of his rewards is huge.”