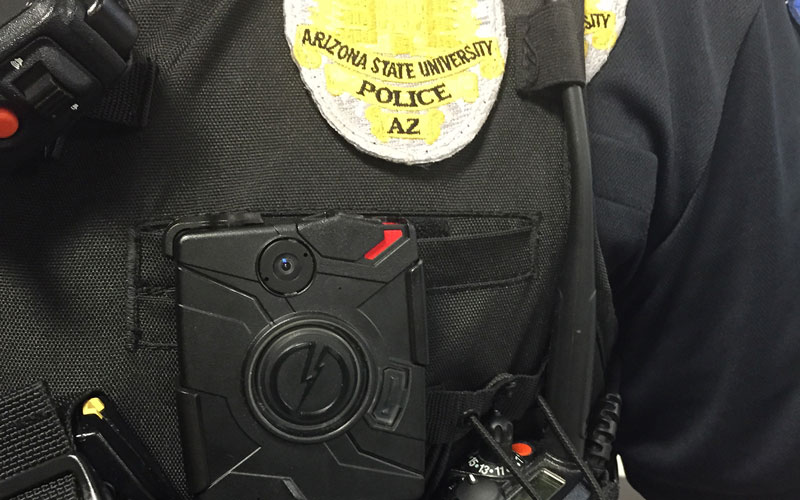

Body cameras have made their way through several police departments across the state, including most recently Arizona State University and Tempe. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

An officer retrieves a small black box charging in the police station and mounts it onto his or her uniform before heading out for the day. Once the officer is on the job, the box is recording.

Police body cameras record every second of the officer’s movements. The camera is constantly recording, but not storing footage. When the officer has contact with someone in the course of duty, the officer presses the record button and the exchange, plus the previous 30 seconds, is captured – providing a video record in case there is an issue on either side.

Officers from Arizona State University, Tempe and Maricopa County Sheriff’s office recently deployed body cameras to their officers, following suit of several other cities around the Valley, including Phoenix and Mesa. Body cameras have been adopted by law enforcement agencies across the nation, capturing interactions with the public and potentially controversial scenes of conflict.

“They provide a good tool of public oversight for police departments,” Will Gaona, policy director for the Arizona American Civil Liberties Union, said. “They offer a way to encourage police accountability.”

Some also find the cameras help officers maintain transparency of their actions.

“It’s helped me be a better officer,” said Ken Crane, president of the Phoenix Law Enforcement Association. “We (Police officers) can sometimes say and do things we regret, just like anyone else. Sometimes the cameras have the ability to have the officers slow down.”

In October, body camera footage showed a Gilbert police officer shooting an armed suspect in a local park. The video shows police yelling at the fleeing suspect, who began firing at the officers, to “get on the ground” and show them his hands. The man was suspected of killing his roommate and boyfriend of his roommate’s daughter.

Body camera footage has also caught a deadly shooting between Cleveland police and suspect Theodore Johnson, who had made threats against his wife and their landlady. The video showed Johnson shooting the officer in the chest. Backup officers shot Johnson shortly after.

The Tempe Police Department has deployed about 100 body cameras, said Lt. Michael Pooley, media relations for the Tempe Police Department. The department is planning to provide body cameras for all officers during the next year. The department is also in the middle of a research project with ASU, which will look at the impact of body cameras on the officers using them and public perception.

“It’s just the wave of the future,” Pooley said.

Nicole Franks, media relations specialist for ASU police, said all ASU officers have been equipped with cameras as of Nov. 6.

“The body cameras are part of our new leadership, new developments and new technology at ASU PD,” Franks said. “The cameras will give an unbiased second pair of eyes to any situation and our officers are very happy to have them.”

Franks said the cameras will not change the way the police serve the university, but instead add a layer of transparency for the department.

“(The camera) doesn’t lie,” she said.

Sgt. Jonathan Howard, part of the Phoenix Police Department’s Public Affairs Bureau, said the department has been using body cameras for the past several years. The department has 150 body cameras deployed to its officers, and plans to continue growth in the program.

Several Valley law enforcement agencies have purchased AXON body cameras from TASER, which has a production plant in Scottsdale. Body cameras cost around $400 each.

Steve Tuttle, Vice President of Strategic Communications for TASER, said the company first began putting cameras on TASER weapons in 2005. After receiving feedback from law enforcement, the company developed a camera to be mounted on the body. TASER AXON body cameras were released in 2009.

Tuttle said departments were slow to adopt the cameras. He said the complaints were not of the technology, but of the camera’s functionality. The three biggest critiques from law enforcement: large size, protruding wires and discomfort for the officer.

“We knew we were on to something very powerful,” he said. “We just needed to clean up the technology.”

The company made adjustments to the camera’s casing, but kept the technology the same. Several studies were conducted following the release of the updated cameras, including a 2012 study of the Rialto Police Department in California. They found a significant decrease in both the number of complaints and the rate at which weapons were drawn by officers.

“If you can drop complaints, you are saving a lot of time on the officer,” Tuttle said. “It then became a powerful tool.”

Tuttle said the company saw an explosion of growth in 2013 following a public outcry for body cameras. He said the company often sees a surge in body camera orders in response to high profile police-community conflicts, such as in Ferguson and Baltimore.

Officers, now adding another gadget to their already fully-stocked belts and vests, have had mixed reactions to the cameras, Crane said. Officers are slowly warming up to the idea of mobile video recording, but he has seen some resistance to the emerging technology.

“I think officers, once they start using it, they see the benefit,” Crane said.

Crane said cameras are here to stay, but departments shouldn’t rush into the technology without proper research and consideration of their surrounding community.

“It’s unexplored territory,” Crane said. “You have to embrace the technology slowly.”

Body cams, license plate trackers, laptops, oh my! I chatted w/ @TempePolice on ways tech changes pd. @cronkitenews pic.twitter.com/gSp3jmwoNe

— Becca Smouse (@BeccaSmouse) November 17, 2015

Procedures

Within that, Crane said one of the most important considerations when adopting a body camera program is creating a comprehensive policy for officer-use.

“The key thing is you have to develop a sound policy on the front end for how it will be deployed, how it will be utilized and how it won’t be utilized,” Crane said.

As of now, departments are responsible for creating their own policies. Tempe officers are required to have their body cameras turned on when the camera is mounted on. They start recording upon contact with individuals from the community. ASU and Phoenix police have similar policies in place.

“Some agencies have an always-on policy, some the policy (is) you will put the camera on whenever you will have contact with the public,” Crane said. “Some agencies have the policy so it’s up to the officer.”

Law enforcement is still working to create policies in the event a mishap with the camera occurs. Tempe said they handle any issues on a case-by-case basis.

Footage from the body cameras is public record. Just as police reports and other media evidence, police redact information that they see sensitive to both the victim and the public.

Before body cameras, video recordings of police and community interactions were caught on cameras mounted on an officer’s patrol car. Videos from dash cameras offered limited coverage, as the lens stayed stationary and no audio was recorded. Some department’s have had disputes with the public concerning video sharing of sensitive material.

In October of 2014, a dash cam caught a Chicago police officer shooting an unarmed teenager to death. The audio-less video showed the officer shooting the teen, who police said had a knife in his hand, to the ground. In the video, several puffs of smoke were seen coming off of the teen’s body as officers continued to fire. Later reports indicated the teen was shot 16 times.

The department withheld the footage from the public following the shooting. A court order required police to release the video, which was made public over a year after the incident occurred.

Crane said departments often look to one another to develop their policies. He said these policies could change by court challenges impacting state or nationwide regulations.

However, Gaona of the ACLU said policies should stay in the hands of the department. He said the limitations of “large blanket rules” from state or national legislature could make it difficult for departments to mold their program to fit the needs for their officers.

“It’s very hard to go back and change a state law,” Gaona said. “Departments can adapt as they learn more about it.”

Challenges (privacy)

Officers have relayed some concerns in the rising use of body cameras concerning policy and discipline of the still-developing programs, director of Arizona Conference of Police and Sheriffs Jim Parks said

“What’s the expectation of privacy? I think that’s going to be the issue,” he said.

Crane said he has seen resistance from members of the public who say officers are invading their personal privacy when entering a home with a camera rolling. He said, however, these are some of the same voices who demanded more transparency of police officers.

“It’s a double-edge sword,” Crane said. “Do you want the cameras or do you not want the cameras?”

Other issues involve the camera’s placement. Just like dash cameras, the visibility of the lens is limited based on the placement of the device.

“It depends where they are mounted,” Parks said. “Body cameras aren’t going to see what’s going on behind the officer.”

Levi Bolton, executive director of the Arizona Police Association, agrees. He said the cameras should be used as a tool to help check accountability and transparency of law enforcement, but doesn’t necessarily tell the full story of every confrontation.

“We are seeing a camera,” Bolton added. “Everything that the cameras see is not necessarily what the officer sees.”

Weather, fast-moving activity and potential risk for injury also play a factor in the use of body cameras for officers. The device needs to be as mobile as the wearer, and be able to withstand extreme temperatures, Bolton said.

“This is technology and it is worn on their body,” Bolton said. “The body camera suffers those same vulnerabilities.”

Department’s are also juggling the issue of storage space. TASER International’s Steve Tuttle said department’s must opt for a cloud-based option for storage.

“If you don’t use the cloud, you won’t be able to handle this in-house,” he said. “It just gets so large that you need the cloud.”

TASER offers their own cloud-based system called Evidence.com, Tuttle said. As officers upload video footage to the cloud, they also have the ability to categorize the footage based on police report and redact sensitive information. The site logs any users who have watched stored footage as a way to maintain chain of custody.

Still, law enforcement officials worry about security, space and price.

“There’s a cost and experience with those things,” Bolton said. “Because of its emerging technology, we have to kind of struggle through those questions.”

Too much tech?

Pooley said body cameras were just another addition to department’s increasing collection of technologically advanced instruments utilized daily by the officers.

“Our agency is very cutting edge,” he said. “We love looking at new technology.”

Pooley said all Tempe officers get iPhones and laptops to use in the field. These allow the officers to stay connected with their in-house Crime and Intelligence Center.

The department also utilizes mobile fingerprint readers, computer programs designed to monitor social media threats and license plate scanners attached to patrol vehicle.

Pooley said the advancing technology has been exciting for the department, but has often kept officers stuck in their vehicles. Now, he said the department is challenged to find an appropriate balance between the technology and actively engaging with the community.

“We have all of the technology,” Pooley said. “Now we’re trying to bring back the old school boots-on-the-ground, be out there and getting to know your neighborhood.”