WASHINGTON – After serving seven years behind bars for securities fraud, Sue Ellen Allen walked out of Perryville Women’s prison in Glendale on March 19, 2009. But even as she walked away, prison followed her. Even as she tried to start a new life, she always had to “check the box” that said she had been convicted of a crime.

“You can move on with your life, you can try to move on, but you always have to check the box,” Allen said. “It never goes away. The idea of serving your time and paying your debt to society never ends, and it’s painful.”

Advocates say that, despite laws prohibiting discrimination, the shadow of a conviction that follows former inmates makes tasks like finding a job or an apartment difficult. That makes it even harder for inmates, often turned out with little preparation and few resources, to start becoming productive members of society.

“Most people go to a halfway house, the halfway house rent is $120 to $150 a week and you are expected to pay that the first week,” Allen said.

“You’re also expected to be able to buy a bus pass or you’re going to be walking, and in Phoenix in the summer that’s pretty miserable,” she said. “You don’t have clothes, you don’t have toilet paper … you don’t have food, you don’t have anything.”

That leads to a revolving door of recidivism that has advocates, from Allen to President Barack Obama, calling for an overhaul of sentencing and the criminal justice system.

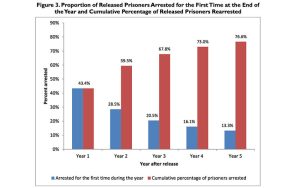

A government study of recidivism among a group of inmates over five years from 30 states showed that the longet a former inmate stayed out of prison, the less likely he or she was to get rearrested. (Chart courtesy Department of Justice)

“We’re spending $80 billion a year incarcerating folks,” Obama said at a White House panel on sentencing reform in November. That money could be put to better use improving police-community relations, developing drug-diversion programs and more, he said.

“We are working on evidence-based approaches to rehabilitation, reducing recidivism and that leads us to save money that then in turn … we can put on the streets,” Obama said.

That just makes sense to Kevin Gay, president of Operation New Hope, a Jacksonville, Florida, nonprofit that works with former inmates to help them survive on the outside.

“Most countries are smart enough to say, ‘Look, we have someone that broke the law, they’re seven times more likely to stay in the cycle of breaking the law, so don’t you think we should be focusing our energies in trying to mitigate those folks from having to come back?'” Gay said. “Most countries do that, we don’t.”

Gay did not always feel that way.

“I was one of those, probably 20 years ago, that said, ‘You know, there is a group of people out there that just want to break the law, don’t want to support their kids, don’t want to support their families,” he said.

That changed when he started working on a mixed-income housing project in Jacksonville and started coming face-to-face with convicts.

“Most of these folks coming home, you know, aren’t coming home and going, ‘Gosh, I want to go back out and break the law again and become a big drug dealer,'” Gay said. “It’s really just, ‘I had one strike against me early on and now no one wants to hire me.'”

That is an example of what U.S. 9th Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski calls one of the many “collateral consequences of having a conviction.” But it shouldn’t be that way, he said.

“You’ve paid your debt to society, done something bad, now you’re going to become a productive member of society,” Kozinski said this fall at a congressional panel on criminal justice reform. “That is greatly diminished if you have this ball and chain that’s always following you around.”

Allen said she never tried to hide the fact of her conviction. In the age of Google, she said, it’s pointless to try. “I would say, ‘Hi, I’m Sue Ellen Allen and I just got out of prison.'”

But Allen considers herself lucky compared to other inmates.

“I was a pretty confident woman when I went into prison,” she said. “I was a college-educated, well-traveled woman.

“I was told over and over, with all the women there, that nobody cares about you. And you are expected to walk out the door … and suddenly jump right into society,” Allen said.

Allen had help. After prison, she lived with friends in North Scottsdale who had a job for her. They helped her found Gina’s Team, a nonprofit that works with inmates in Arizona prisons to prepare them for life on the outside.

Video story by Elizabeth Blackburn

“It is starting inside the prison and giving them that bridge before they get out,” she said of the nonprofit.

For Allen it is more than breaking a cycle, it is breaking a barrier that separates inmates from the rest of the world.

“I feel very connected, it’s not them or us, it’s us,” Allen said of inmates and former inmates. The problem, she said, is that for the rest of the country “it is them or us.”

“We are the them, we are the others that nobody wants to acknowledge and I’m part of that now,” she said.

Gay, who started Operation New Hope 16 years ago, said society will not break the cycle of recidivism if we “just drop people into a community that typically isn’t as welcoming.”

“We’re going to have them right back into that cycle,” he said. “These young kids tell me all the time, ‘My family calls me deadbeat dad, the community calls me deadbeat dad, they don’t know how hard it is for someone with a record to get a job.”

Gay said it’s time for what he calls “smart justice.”

“Smart justice is saying, ‘OK, we want to get people jobs, we want them paying taxes, we want them paying child support,'” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, we don’t want to be soft on crime. Those that have any kind of potential for violence or for security we need to lock them up for a long time.”

Despite the long odds, Gay is hopeful.

“The part that’s exciting … is there is an incredible resiliency to want to be successful, and all the myths that have been perpetrated about not wanting to work is just absolutely not true,” he said.