NOGALES, MEXICO – Dr. Luis Contreras Sanchez was browsing social media when he heard a rapid burst of gunfire just outside his home. It was a night he would not soon forget.

“For a moment I thought my house was going to be shot to pieces, boom, boom, boom,” Contreras recalled gesturing with his hands as he sat in his home that doubles a medical office. “As if there was a war and my house was the target.”

“Everything was quiet, no sound and suddenly the gunfire. I looked out the window and saw someone lying on the sidewalk.”

Outside his building in Nogales, Mexico, 16-year-old Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez was dead on the sidewalk. He had been shot as many as ten times, the majority of the bullets hitting him on the back of his body. The shooter allegedly was Border Patrol agent Lonnie Swartz.

“He must have been a good shot to hit (Elena Rodriguez) so many times,” said Contreras.

After three years of legal battles that have tested the patience of people in Mexico and U.S. justice system, Swartz faces second degree murder charges in the killing of Elena Rodriguez.

The Swartz’s case could set a new precedent for Border Patrol officers’ use of deadly force on the job.

According to a 2013 Arizona Republic investigation, 42 people were killed between 2005 and 2013 by Border Patrol agents or Customs and Border Protections officers. 13 of the 42 killed were U.S. citizens.

An Arizona Republic article from September of this year states at least 10 more people have been killed by Border Patrol agents or Customs and Border Protections officers. Swartz is the third officer since 2005 to be indicted and the only one to be charged by the Justice Department.

The National Border Patrol Council, a union for agents, issued a statement after the indictment.

“It is unfortunate that after three years and after being investigated by multiple local, state and federal agencies and then returned to the field to work, agent Lonnie Swartz is now facing criminal charges,” the NBPC said in a statement on the union’s website.

Shawn Moran, VP of NBPC’s media relations said situations like this “sap the morale” of Border Patrol agents.

On Oct. 10 2012, Nogales Police on the Arizona side of the border responded to a call from a resident about suspicious activity. Two men were attempting to climb the border fence back into Mexico. Border Patrol agents soon arrived on the scene and tried to stop the men.

Swartz allegedly opened fire with a p-2000 semi-automatic pistol, killing Elena Rodriguez in response to the rocks being thrown, according to Border Patrol.

Elena Rodriguez was shot a total of 10 times. One bullet hit his neck, another the side of his head and he had eight bullet wounds on the back of his body according to an autopsy report obtained by lawyers representing the Elena Rodriguez family.

Witnesses told investigators Elena Rodriguez was not with the rock throwers or the men the Border Patrol agents were pursuing. According to Elena Rodriguez’s family lawyers, the teen was walking home after playing basketball.

Images from GoogleMaps taken in 2009 show the spot where Rodriguez was gunned down.

Agent Swartz fired his weapon 100 yards east of where Elena Rodriguez was walking. Swartz’s attorney said his client would plead not guilty at the arraignment Friday.

In 2013 The Police Executive Research Forum, an organization made up of police and law enforcement executives, published a review of cases and policies of U.S. Customs and Border Protection use of force.

The report noted that rocks thrown from Mexico are a danger to Border Patrol agents. “Rocks being thrown … create a significant danger justifying defensive action,” the report said.

“If agents are only armed with deadly weapons, they are left with few options: retreat, or use their firearms.”

The report recommended Customs and Border Protection employ “less lethal weapons” in response to rock throwers.

“The state CBP policy should be: ‘Officers/agents are prohibited from using deadly force against subjects throwing objects not capable of causing serious physical injury or death to them,” the report stated.

Luis Parra, a lawyer for Elena Rodriguez’s family, said the outcome of this case could impact the important relationship between the communities of Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona.

“Frankly I think residents on the Mexican side feel that some cases have not been properly investigated,” Parra said.

“So they are relieved that this case in particular was investigated not only by Americans but by Mexican authorities.”

For Elena Rodriguez’s family, Swartz’s arraignment is a victory.

“Throughout the almost three years, (Elena Rodriguez’s) family has been very adamant seeking transparency and justice and answers,” Parra said.

“They’ve suffered and endured criticism. They feel a sense of relief that this case has taken another step.”

Three year after Elena Rodriguez was killed, life goes on for Nogales residents. People walk past the site of the killing talking on the phone. Students in school uniforms carry backpacks and laugh as they pass Contreras’ home.

For several years a metal cross marked the exact spot where Rodriguez died and served as a memorial on the 10th of every month, the date he was shot. Now, Calle Internacional is in the process of renovation.

Pedestrians have to watch out for gaping holes where the sidewalk should be. The metal cross can no longer be seen, hidden by debris torn up from the road.

“I understand the United States wants to impose a sense of authority,” said Carlos Sanchez standing next to the spot where Rodriguez collapsed and died. Sanchez, 60, works for a bus company, making sure the buses run on time. “But to shoot someone in the back doesn’t make sense. Why treat him like a savage animal?”

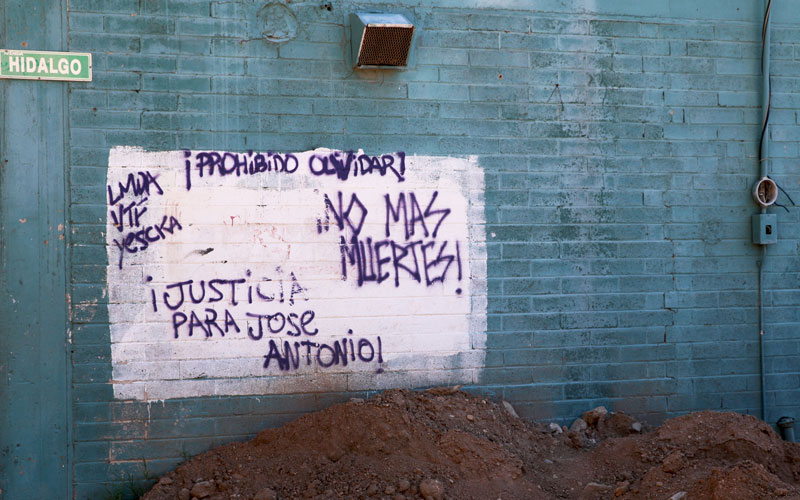

Several of the bullets hit Dr. Contreras Sanchez’ home. Bullet holes still dot the building’s facade. His home and several buildings on the street are plastered with posters and graffiti memorializing Rodriguez and calling for “justicia” or justice.

Dr. Contreras says he wants the walls repainted, the holes covered, but he admits he also has mixed feelings.”No new paint will ever cover or help me forget the past,” said Contreras, who has traveled to Arizona to give his testimony to U.S. investigators about what he heard and saw that evening.

He questions whether investigators looked at video recorded by border cameras on the U.S. side. “They have all the evidence they need.”

That video footage was entered as evidence but has not been made public.

Contreras is frustrated by one realization: “If the situation were reversed, (the United States) would have invaded Mexico,” he said. “The Mexican government is to blame for not immediately demanding the case go to trial right away.”