WASHINGTON – It was just a few years ago that tribal courts would not have been able to prosecute the non-Indian man who beat his Pascua Yaqui partner for failing to make his lunch correctly and not doing the laundry.

Those days are gone, said Pascua Yaqui officials, who said a just-ended pilot program that let the tribe prosecute non-Indians for violence against women on tribal lands was “a very successful program.”

The Pascua Yaqui were one of three tribes – along with the Tulalip of Washington and the Umatilla of Oregon – that tested the tribal prosecutions under the Violence Against Women Act before it became available to all tribes this year.

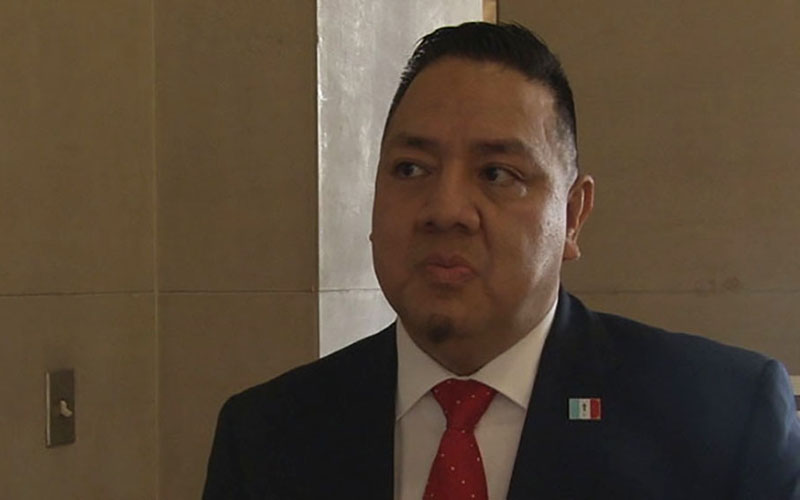

“We’ve had a lot of cooperation with our local U.S. attorney, with our state partners, and so at this point in time it’s been a very successful program,” said Fred Urbina, the Pascua Yaqui attorney general, at a Justice Department review of the program Tuesday.

Oscar Flores, the chief prosecutor for the tribe, said that his office handled 18 domestic violence cases under VAWA “that accounted for approximately 25 percent of my office’s domestic violence caseload arising out of the reservation.”

Those 18 cases involved 15 non-Indian defendants who had had 84 run-ins with Pascua Yaqui police before the pilot program took effect. But authorities didn’t always have jurisdiction to arrest them then.

“We knew we had a problem,” Urbina said before Tuesday’s meeting.

It was even more pronounced for the Tulalip, who said that tribal police had more than 100 contacts with the nine non-Indian defendants the tribe was able to prosecute during the pilot program.

In opening remarks, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch told the tribal officials that the pilot program proved that “with greater control over your own lands and closer partnership with the federal government, justice can and will be done.”

Even as they cited successes, however, the Pascua Yaqui and Tulalip officials said more needs to be done going forward, including delivery of promised funding and the ability to prosecute crimes against children.

After the pilot program ended this spring, the law expanded to allow prosecution by any tribe – as long as tribal courts met certain standards and the proceedings included guarantees of due process rights for non-Indian defendants.

Urbina said none of the $5 million that was authorized in VAWA has been appropriated yet. That funding is important if the program is to expand to the rest of the 566 federally recognized tribes, where he estimated that as many as 10,000 cases have gone unprosecuted because tribes didn’t have the legal authority.

“Each tribe is different and each tribe has a different justice system in different stages of development, so depending on the tribe it could cost as much as $100,000 or it could cost as much as half a million dollars to put a system in place,” Urbina said.

Both tribes said prosecution is also hindered by current federal law that requires physical touching for a charge of domestic violence. That has made it difficult to pursue cases involving threats or damaged property.

Urbina said he knows of three cases where charges were dropped and the accused ended up physically assaulting their victims, which is why his tribe is urging Congress to change the definition of domestic violence.

Tulalip officials pressed for the ability to prosecute crimes against children.

“Five children have been victims of crime in these 11 cases, and we are unable to prosecute on behalf of those children,” said Michelle Demmert, an attorney for the Tulalip. One of the cases made it to the U.S. Attorney’s office, but for the others their “voices are going unheard,” she said.

The tribes also said in their presentation Tuesday that they continue to have issues with interpreters, police training, a lack of access to national criminal databases, jury selection and drug crime prosecutions.

“There’s definitely still some hurdles,” Urbina said.

But there can be no turning back, said another tribal official.

“All women in the United States deserve to be protected,” said Deborah Parker, former vice chairman of the Tulalip Tribes. “And Native women are no exception.”