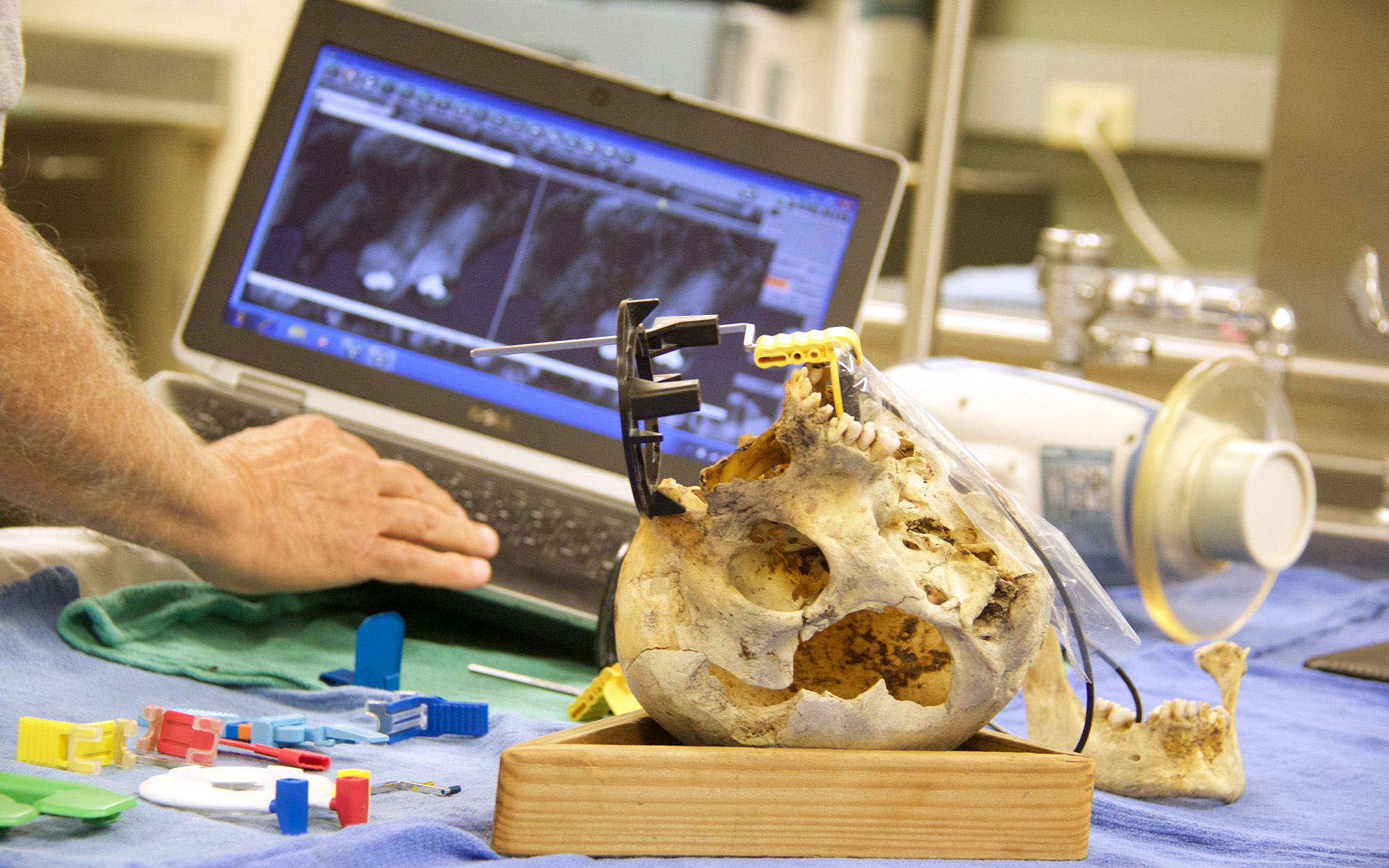

Dental X-rays are a key part of an effort by the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office to address about 200 sets of remains. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

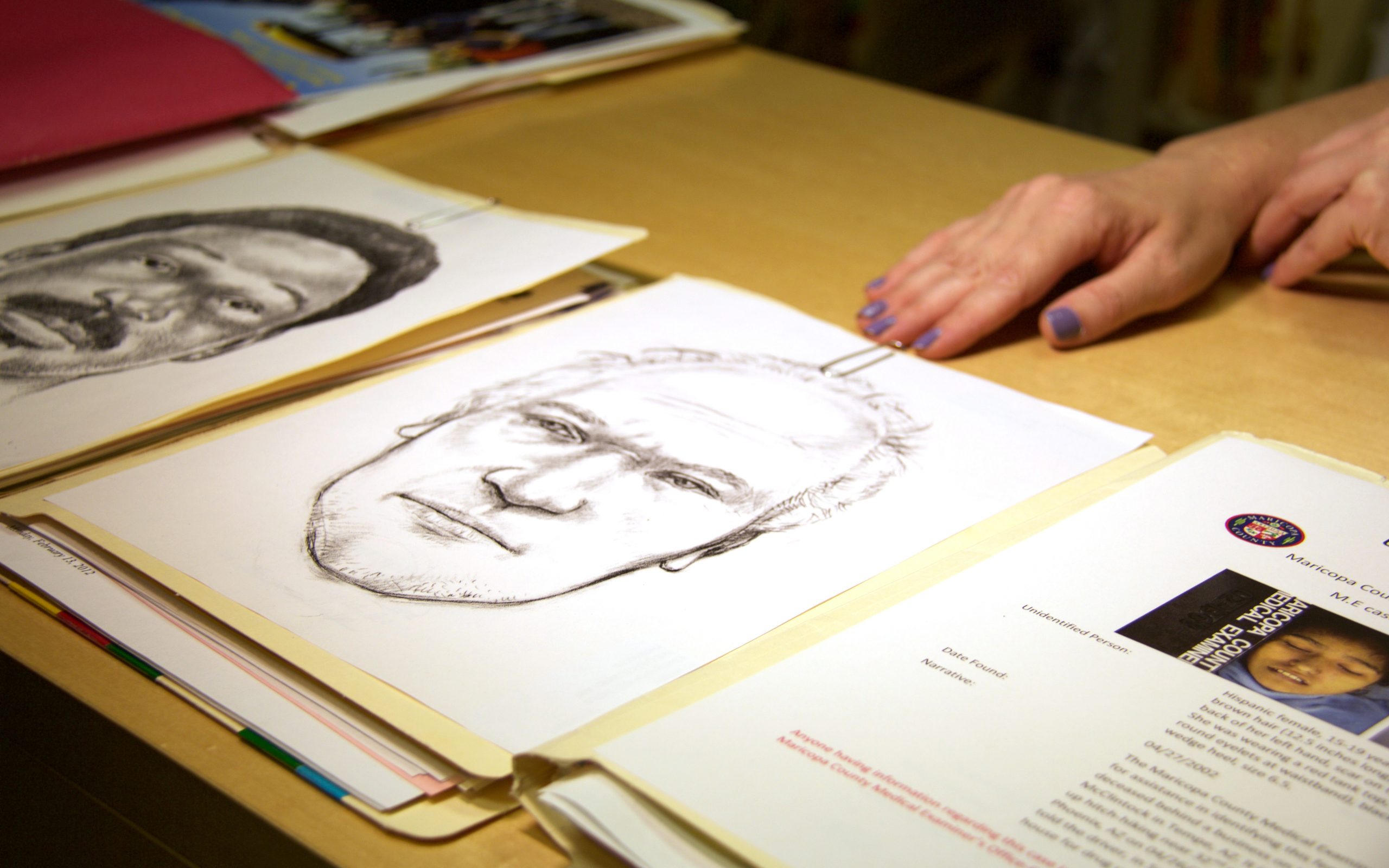

Artists’ renderings are on file with other information on unidentified remains kept at the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

Monica Goodnough, a forensic photographer and fingerprint technician, and Dr. John Piakis, a forensic odontologist, examine unidentified human remains. (Photo by Becca Smouse/Cronkite News)

In 1992, a white male in his late 30s to early 40s was found dead in the Superstition Mountains, slain by two gunshot wounds to the back of the head.

These remains, which now sit on an examination table at the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office, show the man suffered from arthritis in his spine. Today, this seemingly common medical affliction could be the key to learning his identity.

“If someone knew who he was, they would say he complained about back pain all the time,” said Dr. Laura Fulginiti, a forensic anthropologist.

There are roughly 300 sets of remains awaiting identification in Maricopa County. In total, the state has 1,300 open cases, accounting for 13 percent of all unidentified remains in the nation and second only to California.

Now the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office is aiming to reduce that number by connecting missing persons cases to the advanced analysis techniques used by its team of forensic specialists, in part by involving families of the missing.

It’s inviting families to a Missing in Arizona event on Oct. 24 at Arizona State University’s West Campus. Families are asked to bring identifying documents, like dental records and fingerprint cards.

Christen Eggers, community liaison and unidentified decedent coordinator for Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office, said the unforgiving desert is a big reason why there are so many unknown remains.

“Because of the heat, they decompose at a faster rate and they become skeletal remains,” Eggers said. “That makes it so much more difficult to identify the person.”

The majority of the state’s unidentified skeletal remains are found in Pima County, Eggers said.

In Maricopa County, the Medical Examiner’s Office sees roughly 500 cases annually concerning body identification. Of these cases, about two to six go unsolved each year.

“They all have family somewhere,” Eggers said.

Eggers coordinates the unidentified team, made up of a forensic anthropologist, a forensic odontologist, a fingerprint technician and investigators working on these cases.

Dr. John Piakis, a forensic odontologist, focuses on identifying remains based on the characteristics of their teeth.

He starts by taking digital images of teeth in remains with a portable X-ray machine, which can reveal identifying information like missing teeth, molar placement or wisdom teeth. These images can then be compared to dental records already on file.

“If we can get some missing dental records that have similar or concordant points like this, we can possibly do the identification,” Piakis said. “That’s the whole idea of a dental identification.”

Cases that can’t be identified by just visual inspection rely on the work of a dental specialist. Piakis said his department sees about 25 to 30 cases each month, of which he will make five to 10 identifications by dental records.

“If we can get antemortem X-rays before death, then it would be very quick,” Piakis said. “We could do the ID immediately.”

Monica Goodnough, a forensic fingerprint technician, primarily works at recovering badly distorted prints.

Talking w/medical examiner’s office officials on the use of forensics to identify unknown remains in AZ @cronkitenews pic.twitter.com/sXizm6braC

— Becca Smouse (@BeccaSmouse) September 29, 2015

Bodies come in badly decomposed, burned or otherwise visually unidentifiable, Goodnough said. Sometimes she has to chemically rehydrate hands in order to obtain a useable print.

“As soon as you die, you start decomposing,” Goodnough said. “A lot of people don’t consider if you die alone in your house, there’s a possibility you may decompose. We may have to go through other means to identify you.”

These fingerprints are added to a national database and compared for identification.

“We’re able to make the correlation between a missing person and an unidentified decent that we have,” Goodnough said.

Piakis, the forensic odontologist, said the new effort will accomplish more than just closing cases.

“You give families closure,” he said. “That’s the main thing we do here.”