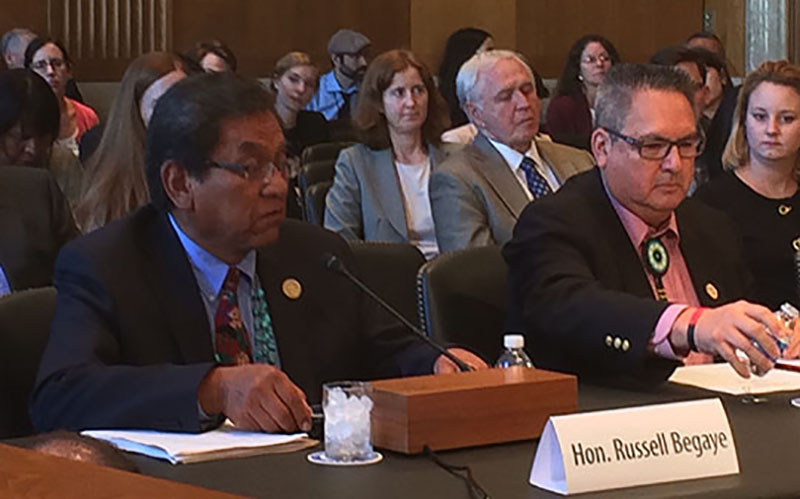

Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye told a Senate committee that EPA’s reponse to the Animas River spill created a “culture of distrust” between the tribe and the agency. {Photo by Charles McConnell)

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy vigorously defended her agency’s response to a spill of toxic chemicals into the Animas River, which occurred under EPA supervision. {Photo by Charles McConnell)

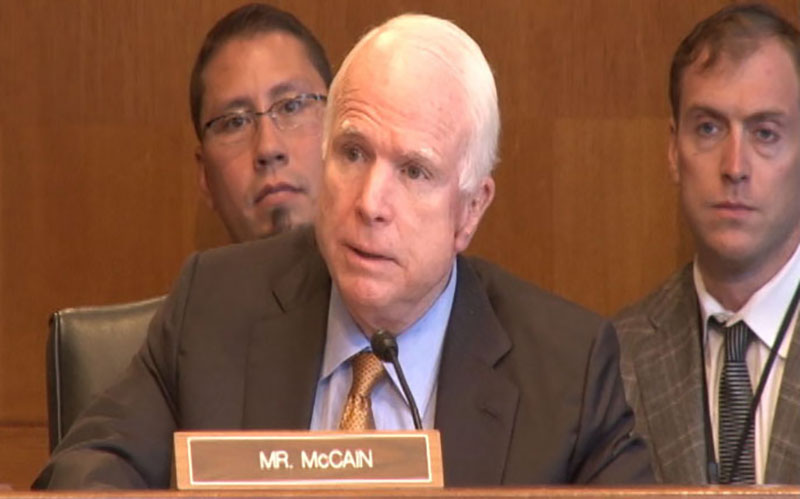

Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, demanded to know why no EPA employees or contractors had been fired in the wake of the 3 million gallon spill into the Animas River. {Photo by Charles McConnell)

WASHINGTON – Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye on Wednesday blasted the Environmental Protection Agency’s handling of a toxic spill in the Animas River, saying the agency’s response left his tribe feeling abandoned, uncertain and hopeless.

“We don’t know who to trust anymore,” said Begaye, who told a Senate committee that in addition to the toxic threats from the spill, desperation over the situation has since contributed to three suicides in a Navajo community.

Begaye’s testimony came during the first of two days of hearings by House and Senate committees into the Aug. 5 breech at the Gold King Mine in Colorado that spewed 3 million gallons of “metal-laden wastewater” into the Animas River.

See related story:

Environmental groups see potential for toxic mine danger in Arizona, officials disagree

The resulting contamination plume flowed into the San Juan River, tainting waters in Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, including large swathes of the Navajo Nation. The release came during work that was being overseen at the mine by the EPA.

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy called the accident “tragic and unfortunate,” but defended what she called a “robust” response by her agency to be claim responsibility and to take clean-up action to “protect human health and the environment.”

“All of the affected residents of Colorado and New Mexico, and the tribes, can be assured that EPA has and will continue to take responsibility to ensure that the gold mine release is cleaned up,” she told the Senate Indian Affairs Committee.

Those assertions were vigorously challenged by other witnesses and by senators, who accused the agency of doing “nothing right” in the aftermath of the spill that they said should never have happened in the first place.

“A spill of this size and magnitude should never be caused by an agency whose sole mission is to protect the environment,” said Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyoming.

Barrasso, the chairman of the committee, said the EPA was not prepared to respond and that it knew of a possible blowout in the mine. He said the spill was preventable, calling it a “a case study of agency incompetence, of an agency incapable of meeting its sole mission.”

When pressed by Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, McCarthy could not name a single agency employee or contractor who has been fired for what McCain called a string of failures in the incident. He said it took two days to notify the Navajo Nation of the spill, that the emergency response was inadequate, that the EPA did not “quickly and routinely” share water monitoring data with the tribes – all of which McCarthy challenged.

The EPA said that metal concentration levels in the water had started returning to pre-spill levels within a week of the breech, and that by Sept. 2 tests showed levels “back to and maintaining” the lower level.

But other witnesses pointed to the long-term threats from polluted sludge that has settled in the river and could be stirred up in the future.

David C. Weindorf, a professor of soil science at Texas Tech University, questioned the EPA response and disputed claims that the water has returned to pre-spill levels of toxins. He asked why workers aren’t out cleaning the sludge left behind as they did after the oil spills of the Exxon Valdez in 1989 or British Petroleum Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in 2010.

Sen. Steve Daines, R-Montana, reminded McCarthy that tribes and the U.S. are supposed to have a “government-to-government relationship,” but that the EPA did not seem to give the same “attention or care” to tribes that they would to Mexico or Canada.

Barrasso said the incident and response show an agency that “disregards the needs of tribes during a crisis.”

Begaye called on the government to compensate farmers for their losses, to help the Navajo Nation do its own water testing and to engage resources of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, among other steps. But he said he does not expect the EPA to honor the promises made in Wednesday’s hearing, adding that there is now a “culture of distrust” between the agency and the Navajo Nation.

Despite that, Begaye said he believes the EPA can repair the broken trust going forward.

“We are strong,” Begaye said. “We are resilient, we will recover.”