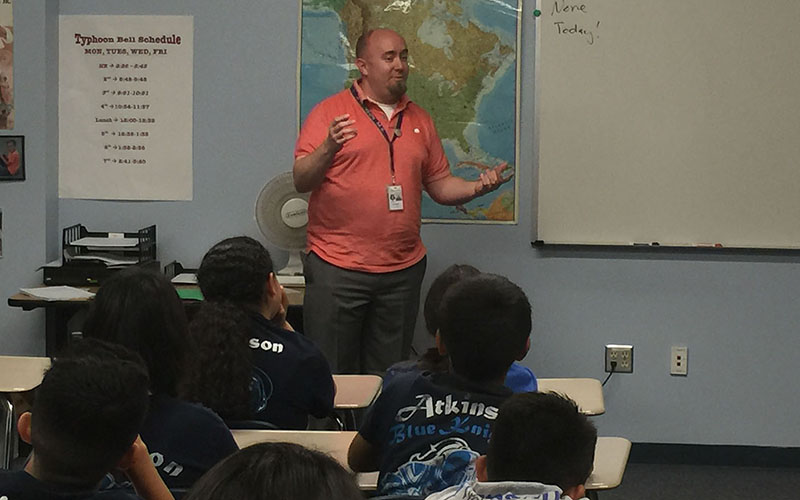

Jacob Lewis includes lessons on 9/11 for his seventh-grade social studies class at Marc T. Atkinson Middle School in Phoenix. He and other teachers say it’s important to help students born after 9/11 understand that it’s not “just another date” in the history books. (Photo by Katie Francis/Cartwright School District)

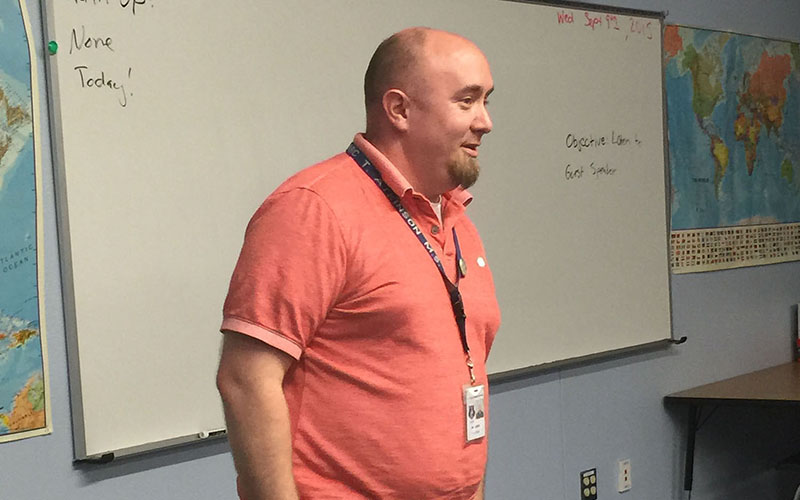

Marc T. Atkinson Middle School social studies teacher Jacob Lewis said that when he first began teaching, students had memories of the 9/11 attacks. But in recent years, he’s been getting students who were born after the attacks or are too young to remember them. (Photo by Katie Francis/Cartwright School District)

WASHINGTON – Every year on 9/11, Arizona teacher Gaye Vaterlaus asks her fourth-grade class to define heroism, and every year they cite heroes like Superman, Spider-Man and Captain America – missing the significance of the date.

“They’re familiar with what the Twin Towers looked like,” said Vaterlaus, who teaches at Robson Elementary School in Mesa. “But a majority of my class is 9 … these kids weren’t even born then.”

“Then” is Sept. 11, 2001, the day that more than 2,700 people died in terrorist attacks, according to a 2004 report from the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, also known as the 9/11 Commission.

For teachers like Vaterlaus, and Phoenix middle school teacher Jacob Lewis, remembering 9/11 in their classrooms is increasingly important as those classrooms fill up with students who have no memory of the day.

“I remember it all very well,” said Lewis, who was 21 when the towers collapsed in 2001.

When he started teaching history at Marc T. Atkinson Middle School in 2007, Lewis’ students remembered it, too, but students in recent classes had not yet been born or were too young to “see on TV what it was like” that morning.

Lewis and Vaterlaus both said they started incorporating lessons on Sept. 11 into their lesson plans about five years ago.

That’s about the time that Jacob Karb, a New York middle school teacher who serves on the board of the National Council for the Social Studies, said he started “noticing a need to incorporate Sept. 11 lessons” into his social studies classroom. Karb, who said he was speaking as an individual teacher and not a board member, said that’s when his students “started to have no memory of it.”

Karb said one student recently came to ask about the Sept. 11 attacks. When he mentioned the plane that hit the Pentagon and United Flight 93 that crashed in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, he said it was the first time the student had ever heard about those attacks.

The Arizona Department of Education’s academic standards for K-12 social studies classes, which outline history lessons expected at each grade level, do not mandate lessons about 9/11, a department spokeswoman said. But the attacks are listed as an example that eighth-grade history teachers might use in a required lesson on the “events of the presidency of George W. Bush.”

The fact that it is not required has not stopped teachers like Vaterlaus and Lewis.

Lewis said he asks parents for permission to show students the documentary “9/11,” by Jules and Gedeon Naudet and James Hanlon. The Naudet brothers were chronicling a rookie firefighter at a New York City fire station when they captured the entire day’s events from the moment the first plane hit Tower 1.

“It captured history as it happened, rather than just the effects of it,” Lewis said.

For Vaterlaus, who is dealing with much younger students, the focus is on the heroes – “hero” in her classroom is an acronym for “helping everyone respect others” – who responded to the attacks.

For 9/11, which is also recognized as Patriots Day, she has her students write peace poems, which they share with the rest of the class. They also read a book about the attacks from the perspective of children, “From the Mouths of Babes: Children Talk About the Day the World Changed,” by Wendy Keller.

Lewis and Vaterlaus say teaching about 9/11 is important to keep the events and its heroes from being overlooked or forgotten – to give it a place in history before this generation is no longer around to share their experiences from that Tuesday.

Without that perspective, Lewis said Sept. 11 will remain “just another date” to students who weren’t around when the attacks occurred.

“For these students, it’s the same thing as Pearl Harbor or the 22nd (of November 1963) when Kennedy was killed,” he said.

“For the generation before, the Kennedy assassination wasn’t history – it was Friday. The generation before that, the Sunday morning of December 7, it’s not history – it’s Sunday,” Lewis said. “It wasn’t history to them, it was the present.”