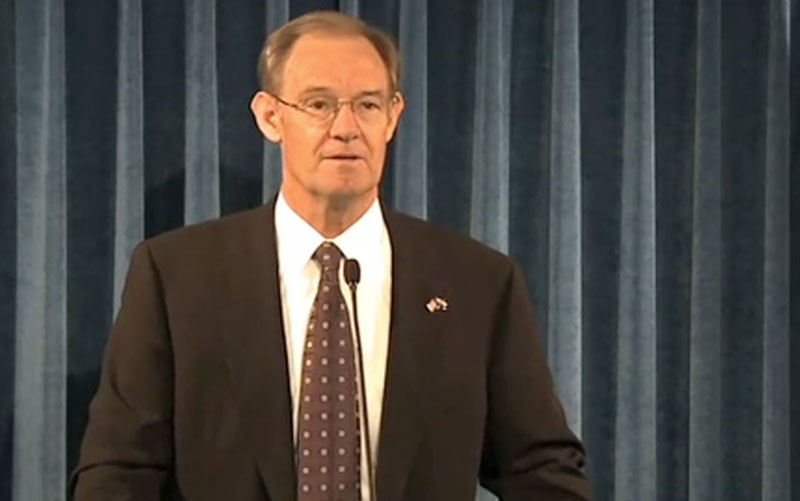

Then-Attorney General Terry Goddard, in a 2010 photo. Goddard said he is confident courts will side with the state in an asset seizure suit from his tenure as the state’s top prosecutor. (Photo by Lauren Gilger)

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals courthouse in San Francisco. The court ordered a new hearing for people who say Arizona illegally seized money in a smuggling probe. (Photo by Ken Lund via flickr/CreativeCommons)

Editors Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly reported the outcome of the two plaintiffs’ efforts to get back the money that was seized by the state of Arizona. Lia Rivadeneyra eventually got her money back but Javier Torres never did, their attorney says. The story below has been revised to reflect the correct information. Clients who used this story are asked to run the correction that can be found here.

WASHINGTON – A federal appeals court Thursday ordered a new hearing for two people who claim Arizona prosecutors unconstitutionally seized money transfers from them as part of an investigation into human smuggling.

Neither Javier Torres nor Lia Rivadeneyra was ever charged with a crime, but the state still seized hundreds of dollars in money transfers from each because the transfers fit a pattern used by traffickers, or “coyotes.”

The two sued and sought to represent the class of people from whom the state seized more than $9 million through warrants issued between 2001 and 2006 as part of the investigation.

But a district court threw out their suit, saying that then-Attorney General Terry Goddard and Assistant Attorney General Colin Holmes were immune from prosecution for their actions.

A three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld most of the lower court’s ruling Thursday, but agreed with attorneys for Torres and Rivadeneyra that the prosecutors might not have enjoyed absolute immunity as individuals.

It ordered the case back to district court with instructions to consider whether Goddard and Holmes were immune for actually serving the warrants – which the court said is a police action and not the protected action of a prosecutor.

Goddard said Thursday that the court’s ruling turned on what he called “a very small part of what we did and in my opinion, the most innocuous part.” He said he was pleased overall with the ruling and confident that he and Holmes’ estate – Holmes died while the case was pending – will win when it returns to district court.

The attorney for Torres and Rivadeneyra also welcomed the chance to press their case in district court again.

“It’s taken so long,” said Matthew Piers, who said his clients were victims of “monetary profiling” from a warrant that was based on the type of transfer rather than information about the people making the transfer.

The money seizures began as part of a state effort to stem what Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski called “a coyote problem. Not the four-legged furry kind that occasionally abscond with pets, but the kind who smuggle undocumented aliens into the United States for a fee.”

Kozinski said state officials executed more than 20 warrants to seize thousands of wire transfers that they claimed were “highly likely to be connected to criminal conduct.”

The warrants targeted money transfers of certain amounts, sent from specific states to Arizona or to the state of Sonora, Mexico, during the spring and fall, which are peak times for smuggling activity.

The warrants were presented to Western Union, which automatically diverted suspect transfers into a state account. State officials then notified people whose transfers were diverted, giving them a chance to get it back.

The appeals court said prosecutors were protected for their role in preparing and drafting the warrants, because those are prosecutorial actions. But it noted that Holmes served the warrants to Western Union, which it called “the functions of police officers, not the ‘traditional functions of an advocate.'”

“Now, the court of appeals is saying some of what you did has immunity, but not all of it,” Piers said.

He said the warrants “involved literally thousands of seizures.” For his clients, he said, the state seized money that one was sending to pay off the debt on a car he sold and the other was sending to help his brother.

Piers said Rivadeneyra eventually got her money back when a court said the state could not block transfers to Sonora, but Torres never did. But Piers also said the money should not have been taken in the first place and his clients should not have had to fight to get it.

“Why should I have to talk you into giving it back to me?” Piers asked. “It’s mine.”

But Goddard said the state “bent over backwards for people whose money was at jeopardy.”

“After the money was taken it went to another hearing” giving people another chance to get their money back, said Goddard, adding that there were “no bad motives” in the investigation.