The Hualapai Mexican vole, found in northwestern Arizona, had been listed as endangered, but federal officials are now proposing taking it off the endangered species list. (Photo courtesy the Arizona Game and Fish Department)

WASHINGTON – Federal officials said Thursday they want to remove the Hualapai Mexican vole from the endangered species list, a move environmental groups immediately called a “bad idea.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has not proposed “delisting” the vole because its population is stabilizing. In a Federal Register posting Thursday, the service said it no longer believes the vole is a subspecies of the larger Mexican vole species.

Critics of the proposal disagreed, and said the Hualapai Mexican vole, which is found in northwestern Arizona, is “definitely not recovered.”

“The literature is sort of conflicted,” said Brett Hartl, endangered species policy director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Rather than taking a cautious and prudent approach, they’re just sort of rushing to delist because the state of Arizona wants them to.”

But supporters of the delisting say it’s long overdue.

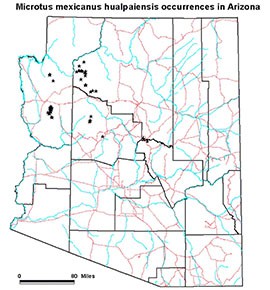

Stars on this Arizona Game and Fish Department map show areas where Hualapai Mexican voles were believed to be living. Click on the map for a larger version. (Photo courtesy Arizona Game and Fish Department)

“This decision is a long time coming and we’re glad to see the service doing its job and taking a responsible approach to delisting a species that is in no need of protection,” said Margaret Byfield, executive director at the American Stewards of Liberty, in an emailed statement.

Byfield’s organization, which says it is dedicated to protecting private property, had threatened earlier this year to file a lawsuit to delist the vole, which was first classified as an endangered species in 1987.

It was then that the Hualapai Mexican vole was classified as a subspecies, but the service said Thursday that listing “is now in error.”

“The currently listed subspecies is not a valid taxonomic subspecies,” the service said in its announcement.

“The Endangered Species Act is dynamic,” said Jeff Humphrey, a spokesman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “It recognizes that science will progress and science will get more and better information on species.”

But Hartl questioned the service’s “better information on species.”

“Instead of doing more research and conclusively answering that question they’re just moving to delist it, and that’s not a particularly prudent course of action,” he said.

The 4- to 6-inch Hualapai Mexican vole lives in moist areas near permanent or semi-permanent bodies of water near ponderosa pine trees. The mouselike animal eats mainly the grasses that commonly surround its habitat, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Its 1987 declaration that the animal was endangered said its “small patches of suitable habitat” were being threatened by livestock grazing, human recreation and other activities.

But Byfield said in her emailed statement that “when a species is listed needlessly … the effect to landowners and local governments can be devastating.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service announced in 2010 that it would review the status of the vole, along with other endangered species.

Should the Hualapai Mexican vole be removed from the list of endangered wildlife, oversight of its management and wellbeing would transfer back to the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

That’s not something that Hartl thinks would be in the vole’s best interest.

“I don’t think the state of Arizona is particularly keen on managing a vole, so I don’t imagine there will be much conservation of this population of the vole,” he said.

Officials with the Game and Fish Department, and with the Mohave County government, which had joined Byfield’s group to push for delisting, did not immediately return calls Thursday seeking comment.