Arizona’s Pinto Creek has been subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act, but questions have been raised over whether other streams, wetlands and the like are regulated. New rules from the EPA aim to settle the issue. (Photo courtesy Michael Brady)

WASHINGTON – A new federal rule was meant to clarify the scope of the Clean Water Act, but some critics are saying the 300-page document has done little to clear up the issue since its release this week.

The final version of the “Waters of the United States” rule was released Wednesday by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers after more than a year of study and 1 million public comments.

The rule aims to clear up which waters are subject to pollution regulation standards of the 43-year-old Clean Water Act, which applies broadly to “navigable waters” of the U.S.

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy said Wednesday that the rule “established clear boundaries here that we have never done before.”

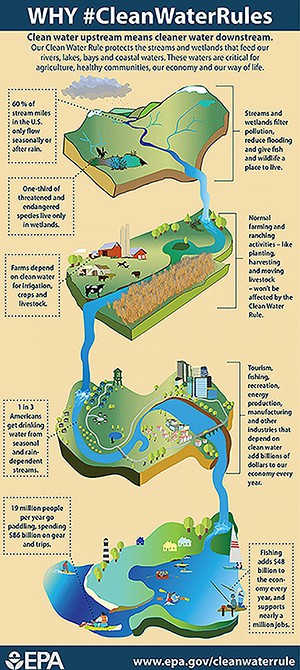

Federal officials say the Waters of the United States rule does not expand the Clean Water Act’s reach, but merely clarifies where it should apply. (Chart courtesy Environmental Protection Agency)

The rule does list several very specific categories – “territorial seas” are subject to the Clean Water Act, for example, while puddles are among a list of waters specifically that are excluded, along with artificial ponds, converted croplands, most ditches and more.

But in between those extremes is a broad range of waters that could qualify for coverage based on a number of criteria. Those factors include proximity to other bodies of water, presence in a 100-year floodplain, potential to “significantly affect” life and water quality in navigable waterways, among other factors.

The document also lays out precise definitions for standards like “adjacent,” “neighboring” and “tributary” and spells out rules for how seasonal pools should be measured.

“So you see the problem here is it’s anyone’s guess to what constitutes as waters of the United States,” said Reed Hopper, principal attorney for the Pacific Legal Foundation, which advocates for property rights.

“It muddies the water. It’s more confusing,” he said.

On the other hand, environmental activist Brett Hartl worries that the definitions spelled out in the rule might be too specific, leading people to avoid going to regulators when they would otherwise do so.

“A lot of people are going to say, ‘Am I 1,500 feet away (from a covered body of water) or out of the floodplain?'” said Hartl, the endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Once they have figured that out, they might say, “OK, now I’m done,” and not check with the Army Corps or the EPA to see if they need a permit for a water-related project, he said.

See related story:

‘Waters of U.S.’ rule does little to settle feud over EPA reach on regs

He joked that before he fully understands the impact of the rule, he may have to spread the pages of it out on the floor to compare them.

Hopper said the specifics of the rule won’t matter in the long run if final say is left to the regulators.

“It really doesn’t matter what the regulations say because the government officials can assert the specific waters that are covered,” he said.

An official with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality said this week that the agency is still studying the language of the rule.

The rule is not scheduled to officially take effect until late July, 60 days after its release this week.

“Unfortunately, it will probably take years” to see how this all works out, Hartl said.