For hundreds of years, Native Americans have used eagle feathers for religious and cultural purposes. But the government closely regulates the ability to obtain such feathers, sometimes leading to black market activity.

“We use a lot of the eagle feathers to help us with our spirituality,” said Anderson Hoskie, a Navajo medicine man. “It is part of our ceremonies, our healing and it is also in a lot of our Navajo stories.”

The Native American community can legally obtain eagle feathers through a federal depository, but it’s an arduous process.

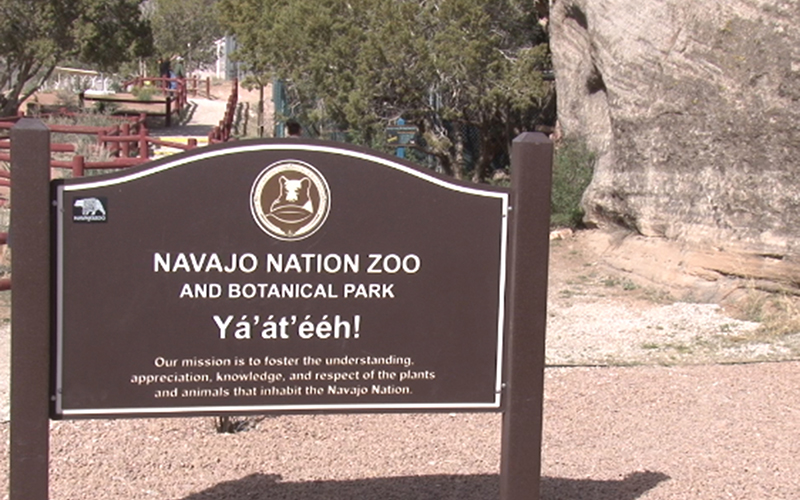

The distribution system is backlogged, and numerous people are on the waiting list, said David Makisic, coordinator for The Navajo Zoo and Botanical Park in Window Rock. He said it could take three to four years to get a feather.

One tribe now has more direct access.

The Navajo zoo, the only Native American zoo in the U.S., is part of a pilot program to legally release golden eagle feathers molted from its live birds to the Navajo people.

The tribe received a permit in 2012 to provide the feathers, and members can submit applications to the Navajo Department of Fish and Wildlife. The zoo can provide a two to three week turnaround on applications, Makisic said.

The problem: The zoo only has four eagles.

“That’s not a lot of feathers to be able to supply the whole Navajo Nation with the necessary needs for eagle feathers,” Makisic said. “But, we are making an attempt to provide those feathers to the people that need them the most.”

It’s also expensive to keep the golden eagles.

Feeding one costs $1,000 a year, said Elden Brown, the legal instruments examiner for the southwest region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

And there’s a difference between the quality of feathers: The molted feathers come from live eagles, while the feathers from the depository come from dead eagles, officials said.

“It is like apples and oranges to which one is better,” said Greg Hughes, migratory bird office chief for the southwest region of the wildlife service.

The Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940, amended in 1962 to include protection for golden eagles, makes it illegal to take, transport, sale, barter, trade, import and export, and possess eagles without a permit.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act also prohibits the possession of eagles or their parts, including feathers, without a permit.

Years of habitat loss from urbanization, exposure to chemicals used in agriculture, and poaching caused the population of eagles to decline by an alarming rate, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

However, in recognition of the significance of eagle feathers to Native Americans, the agency established the National Eagle Repository in the early 1970s to provide feathers for ceremonial purposes. The agency issues permits to members of federally recognized tribes to obtain eagles or eagle parts.

Even with multiple outlets, some people turn to illegal measures to obtain feathers.

“There is a back market for (eagles). They are highly sought after,” said Phillip Land, a special agent in charge for the southwest region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“A full tail fan could go anywhere between $1,000 and $1,500,” Makisic said.

The illegal activity affects the long term viability and sustainability of the golden eagle and other migratory bird populations on the reservation, said Gloria Tom, the director of the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife, who was quoted in a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report about illegal bird trafficking.

“There are serious repercussion for people caught buying, selling and trading eagle feathers,” Makisic said, “There is jail time. There (are) heavy fines.”

Cronkite News reporter Gabriel Cordoba-Hawthorne contributed to this article.