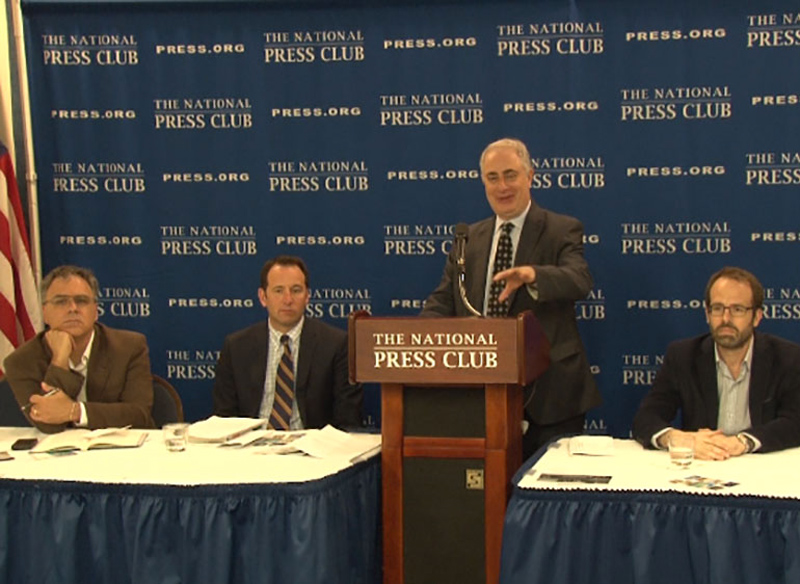

WASHINGTON – A panel of experts was in Washington this week advocating for more fun in schools – more “hard fun.”

That is the term that was being used by industry and government officials who were part of a panel Thursday that talked about how video games and gaming can help students learn.

“We’ve been trying to find a way to put those two together for centuries,” said Greg Toppo, a national education writer for USA Today.

“I think one of the most exciting things is that this movement has that at its forefront,” he said. “It’s always thinking about hard fun.”

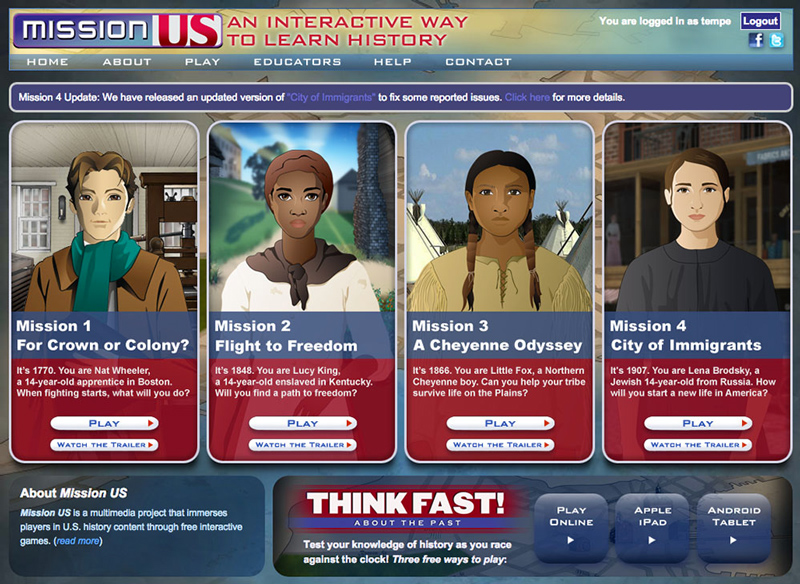

Hard fun is a goal that game designers at New York-based Electric Funstuff keep in mind for their projects, said CEO and co-founder David Langendoen. He believes that games are much more than just an activity.

“You’re not just making a game – it’s a much broader, bigger experience,” Langendoen said. “You’re not just designing what’s engaging, or this interaction, you’re designing a whole ecosystem of materials, professional development, lesson plans and ways that the teacher can use this.”

Panelists at the National Press Club event said schools have not always been eager to incorporate games into the curriculum. But that outlook is beginning to change.

Edward Metz, the program manager of the Department of Education’s Small Business Innovation Research program, said he watched attitudes related to educational games change over the years.

“Seven or eight years ago the question was, ‘Are games appropriate for schools and for education?'” Metz said. “And I think that question has now been replaced by, ‘How can we optimize games to be used within the current structure of schools, teaching and learning?'”

One of the first to ask that question was James Gee, an education professor at Arizona State University who wrote one of the first books on video games and education, according Langendoen and Metz.

“Jim Gee’s original book, ‘What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy,’ really was the thing that set up all this academic interest in gaming,” Langendoen said.

He said Arizona had become “a hub for … this academic side of thinking and research” – research that will be critical as advocates attempt to make games more prevalent in the classroom.

“Why is a teacher going to shift her entire way of doing things, figure out how to use this new technology, convince her principal that (games) are the thing to do, unless there’s something that shows it actually really works?” Langendoen asked. “If we can’t prove it, schools won’t use it.”