The Arizona Prison Complex Florence houses more than 4,000 inmates (Photo courtesy of Kevin Wright)

Matthew Rohrbach has no children of his own, just his wife and a 170-pound Great Dane named Loki. Instead, he has he has been involved in Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arizona and is matched with 15-year-old Mick — whose father is in prison.

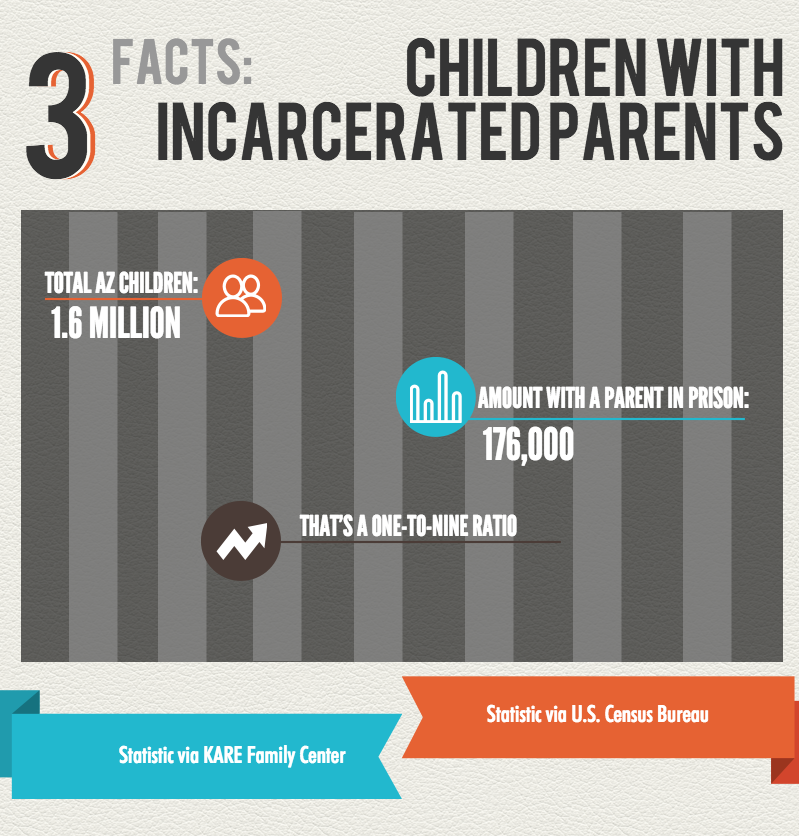

Mick is among at least 176,000 Arizona children and teens that have a parent serving time, according to the Tucson-based KARE Family Center, which help relatives cope with caring for children whose parents are imprisoned.

When he was three years old, his father was arrested for manufacturing and selling methamphetamine, along with charges of reckless child abuse related to his drug crimes, according to court reports.“Multiple times so far, he’s told me how his dad was going to get an appeal hearing and potentially get out early,” the 38-year-old Rohrbach said. “As far as I know, the guy doesn’t stand a chance of getting out before Mick turns 21.”

According to inmate information from the Arizona Department of Corrections, his father is not scheduled for release until 2024.

“I don’t like seeing the kid think his dad’s going to get out when his dad’s not,” Rohrbach said.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates there are 1.6 million children living in Arizona. One in nine has a parent who is in prison, or on parole or probation.

Rohrbach said Mick’s family now has a limited income. His mother also was charged in connection with his father’s crimes and received two years of probation, according to records.

On any given day, there are an estimated 2.7 million children in America with at least one parent in prison or jail, reports the National Resource Center for Children of the Incarcerated based at Rutgers University in Camden, N.J.

Matthew Rohrbach volunteers with the Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arizona is matched with a teenager whose father is in prison. (Photo courtesy of Matthew Rohrbach)

“While many of the risk factors children of incarcerated parents experience may be related to parental substance abuse, mental health, inadequate education, or other challenges, parental incarceration increases the risk of children living in poverty or experiencing household instability independent of these other problems,” says a report from the center.

Family members and caregivers of these children also “bear numerous burdens, including stigma and shame associated with having a family member in prison, increased financial strain, physical and emotional stress, and lack of external resources,” according to the center.

Mick talks to his father and the two have discussed starting a business when he’s released from prison by turning old medical buildings into rehabilitation centers. But Rohrbach doesn’t think this is in Mick’s best interest. Mick has talked about joining the U.S. Navy; Rohrbach encourages this.

“He needs that structure, that disciplinary figure above him,” Rohrbach said. “His behavior indicates that he’s a lot more flexible to go outside of the rules. The nature of both of his parents’ history … I think he’ll still have the potential for getting into trouble because of what he saw growing up.”

Kevin Wright sees the impact on children firsthand.

Wright, a criminology and criminal justice assistant professor at ASU, is conducting a study on visitation at the Arizona State Prison Complex in Florence.

He said that younger kids are often excited to visit. However, preteens and teens place more importance on self-image, and Wright said they dislike the visits.

“You might be embarrassed that you have a parent that’s in prison,” Wright said. “When you’re that age, the most important thing is your friends and whatever you’re doing that day.”

He observed two girls visiting their father. One was about 12 years old and one was about five.

The younger daughter laughed, was energetic, and treated the visitation center as if it were a “playground,” Wright wrote in one of his reports, “Moving Prison Visitation Research Forward: The Arizona Prison Visitation Project.”

“The younger daughter was so happy to be there, bouncing all around and at one point she was like, ‘Daddy, where are we?'” Wright said.

The dad seemed uncomfortable. He avoided the question. The older daughter, with her arms crossed, responded abruptly.

“Prison. We’re in prison.”

Wright said he never planned on getting involved in prison visitation. He didn’t know where to go with his sociology degree, but a professor recommended an internship with the Maryland Division of Corrections.

He met with prisoners who were to be released within 30 days.

“I was struck by how bleak their futures were,” he said in an email.

Some couldn’t read or write; others had diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis C. Some didn’t even have identification.

“It was just tough to think that they would be able to lead law abiding, productive lives going forward,” Wright said.

He became involved in visitation privileges to help prisoners “maintain some sense of a normal life.” Wright said it would be easier for them to transition back to the outside world if they were in contact with friends and family throughout their incarceration.

As children reach their teenage years, their dependency on public perception increases. According to the Washington D.C. based Urban Institute, late adolescence begins at age 15 — an age in which they crave “increased independence.”

Pat Krug has been a mentor with Big Brothers Big Sisters for more than 20 years. She has seen this with the girls she has mentored.

“All the other (matches) ended when my ‘little’ got to be around 15, when they just kind of got a busy social life of their own and seeing me wasn’t a priority,” Krug said.

Ann, her current match, will be 15 in February.

“This feels a little bit like that,” said Krug, who has no children of her own. “I’m not quite ready for this one to end, but we’ll see what happens.”

Krug says it’s a healthy to be more independent, and she has learned to take a step back and accept that the girls would prefer to go to the mall with friends rather than seeing a movie with an adult.

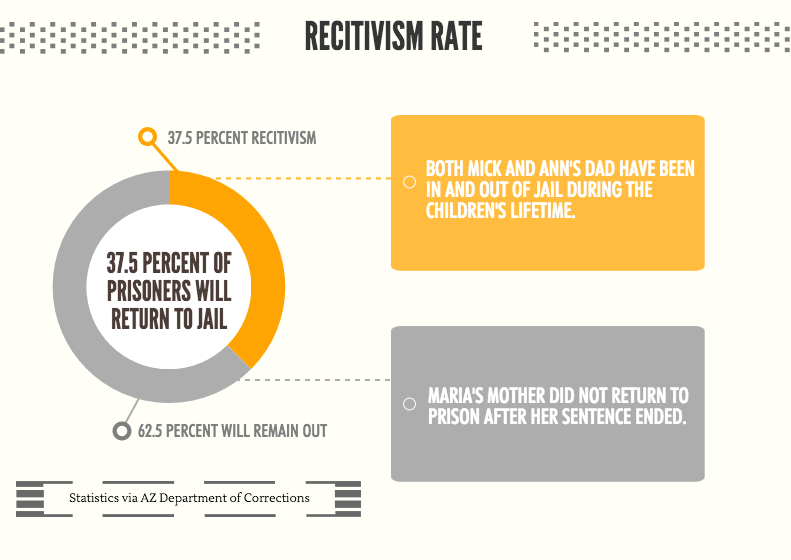

Ann’s father has been incarcerated multiple times, mostly for drug-related crime. His multiple-arrest record is not unusual — according to the Arizona Department of Corrections, Arizona’s recidivism rate is at 37.5 percent.

“He has a drug habit, so (Ann) finds it hard to understand that when he tells her, ‘I love you’ and ‘I’m going to make it on the outside’ and ‘I want to see you’ and all this, she takes that at face value,” Krug said. “Then he ends up back in jail and she thinks that he lied to her.”

Phone calls between Krug and Ann are becoming infrequent and often, the family’s phone service is shut off because they can’t pay the bills, Krug said.

Krug’s previous match in the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, a girl named Maria, had similar problems.

Maria is the middle child in a family that consists of at least six siblings. Krug met the family when Maria was six years old. The girl lived in a house that “should’ve been condemned.” Cockroaches skittered about the floor. Windows were shattered and the roof leaked, she said.

The family moved multiple times. At one point, the family of seven lived at a motel where the mother worked as a maid. They didn’t have a home phone until Krug bought one for them.

“I don’t always have money to donate places but I always have time,” Krug said. “It’s kind of just my way of giving back.”

Maria’s father was not in her life. Her mother was arrested and pleaded guilty to charges of possession of marijuana. She was jailed for about six months.

Maria’s aunt took care of the children and her own baby while the mom was incarcerated. One of Maria’s sisters was pregnant at age 17. Another was pregnant at 16. Krug is not in direct contact with Maria, now about 20 years old.

But judging from pictures Krug sees on Facebook, she said Maria may have a baby of her own.

Krug says she tries to keep her role as a mentor in perspective.

“I have to remind myself I’m the big sister, I’m not the parents’ savior, I am not their financial supporter,” she said. “You are, in theory, a big sister who’s trying to grow and develop that person.”