Nelson Diaz fries empanadas in his home kitchen to be delivered across Panama City. In Venezuela, he was a pharmacist, but in his new home country, food sales earn him just enough to pay rent and send a little to his mother back home. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Fleeing chaos, Venezuelans flock to Panama but struggle to find work

By Anthony J. Wallace/Cronkite Borderlands Project |

PANAMA CITY, Panama – In Venezuela, Nelson Diaz worked as a pharmacist and lived in the suburbs in an “American-style” house with a big backyard covered in lush grass.

Now he shares a cramped, dimly lit home with his brother, sister-in-law, niece and nephew in a dangerous part of Panama City. Diaz, 27, makes $1,000 a month selling homemade empanadas to neighbors. His business enables him to send $100 each week to his mother; his greatest wish is to go home and “hug her for a month.”

Emmanuel Viloria and his wife, Edmily, both 27, left their young daughter behind with family when they immigrated to Panama four years ago. Seven days a week, Emmanuel darts through Panama City’s busy streets on a motorcycle delivering food. His earnings provide for his daughter in Venezuela.

Anibal Rey arrived in Panama on a tourist visa in 2014. He was 20 and had $5 in his pocket. In between working 12-hour shifts as a security guard and janitor, he found time to write songs and now works full time as a musician in the capital. The lyrics to his most recent song are about missing home: “I miss your sun and your warmth / It’s in my heart always.”

None of these immigrants had wanted to leave Venezuela.

“We neither had the wish or the desire to leave the country,” Diaz said. “We had it all (there).”

Except for a way to survive.

Hyperinflation, dire shortages of food and medicine, rampant crime and the erratic rule of President Nicholas Maduro have driven out 5 million Venezuelans – over 85% of whom have left since 2015, according to IOM, the U.N. immigration agency.

Diaz, Viloria, and Rey are part of the “third wave” of Venezuelan migrants to Panama that started in the mid-2010s. They are younger and less affluent than those who came before them and have been received less hospitably by Panamanians.

There are an estimated 150,000 Venezuelans in Panama, 50,000 of whom are undocumented, according to HIAS, a nonprofit founded in 1881 that aids and assists refugees across the globe. Nearly all the rest are noncitizens but have at least temporary legal residency. Many have difficulty finding jobs.

Diaz’s story – medical worker turned food laborer – is typical for immigrants who are trained professionals. By Panamanian law, 56 professions, including pharmacist, pilot, chemical engineer, economist, doctor, nurse and dentist, are reserved for citizens only.

To work legally in other jobs, immigrants must have legal residency and apply for work permits, which can be a lengthy and costly process. They often turn to the informal economy, working for cash and without benefits.

Rey, who remains undocumented, makes his living playing live shows and writing songs for commercials. Diaz has a temporary work permit and earns all his money from selling his empanadas. Viloria works legally, albeit dangerously, delivering takeout on a motorcycle.

‘Trying to feel like this is home’

Appetito24, an app-based delivery service similar to Postmates, is a major employer of third wave Venezuelans living in Panama City, said Roberto Mera, Panama country director for HIAS.

On an overcast Saturday afternoon in March, not far from the capital’s main shopping mall and iconic skyscrapers, a group of motorcycle-delivery drivers in matching red shirts lean on their bikes and laugh like school boys. It’s a slow hour.

Viloria spends hours here awaiting dispatch. The 15 or so young men with him are bonded by a common plight. Most moved to Panama within the past five years, all are from Venezuela and all miss family left behind. At least once a month, they shoot pool at a local bar.

The makeshift community helps, but homesickness weighs on them.

“We’re trying to feel like this is home,” Edmily Viloria said. “We want to bring our family.”

Delivery is a dangerous job. Many of Viloria’s co-workers have died in traffic accidents, leaving their families with the decision of whether to pay $1,600 to repatriate their bodies to Venezuela. But the pay is decent. Drivers say they make about $300 a week – enough to pay the rent and send some back home.

The Vilorias live in a basement apartment off a busy street shaded by high-end high rises. They share the space, which is just a couple miles from where the Appetito24 group meets daily, with one of Emmanuel’s co-workers.

On a Thursday morning, Emmanuel brews coffee and dresses for work. It’s a rare moment when he and Edmily are awake at home at the same time.

“One of us is always working,” he said. Later that afternoon, Edmily started an all-night shift as a nightclub hostess.

“It’s a little depressing,” she said, “because in my country, I talked to my family, my daughter. We’re alone here.”

The couple left their daughter, Emma, to live with her grandparents in Venezuela when she was 5. She’s 9 now.

“It feels bad, so we tried to get her to understand the situation,” Edmily said. “The first year was difficult for her because she thought that we didn’t want to bring her. But it was because I didn’t have the papers to get her in with a visa, and she didn’t have a passport.”

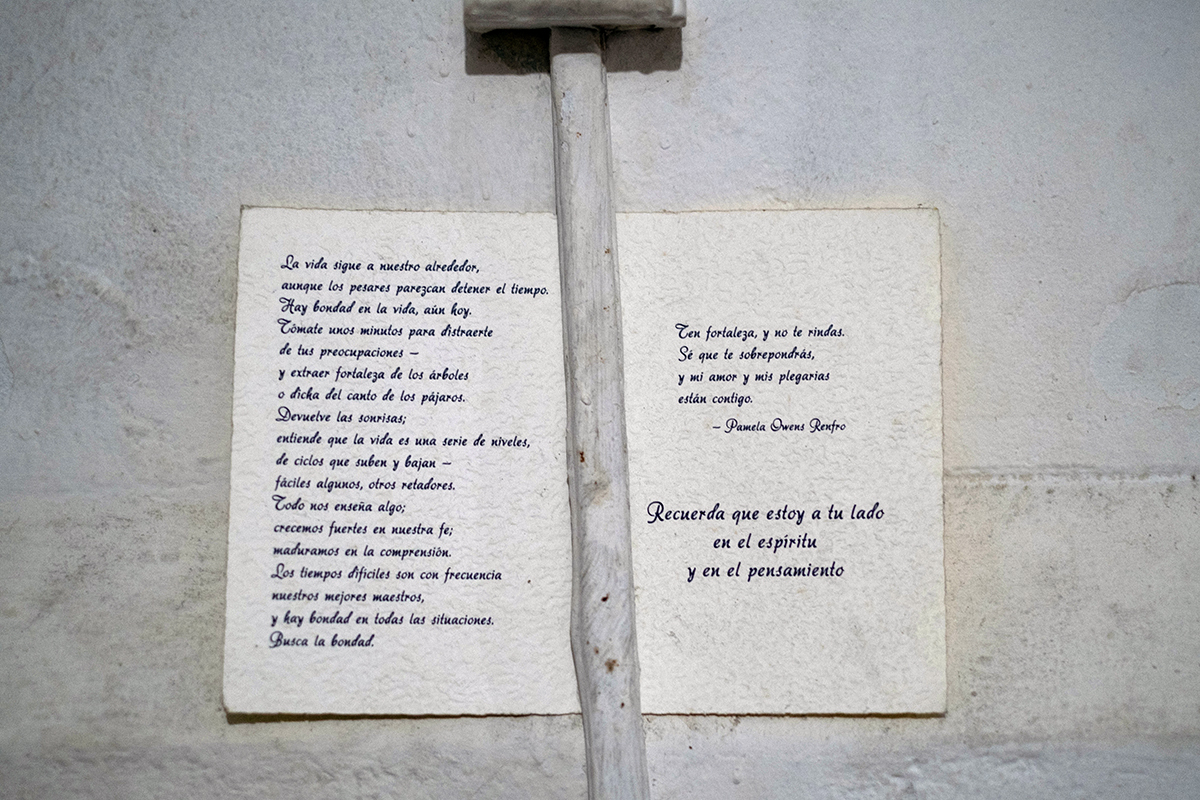

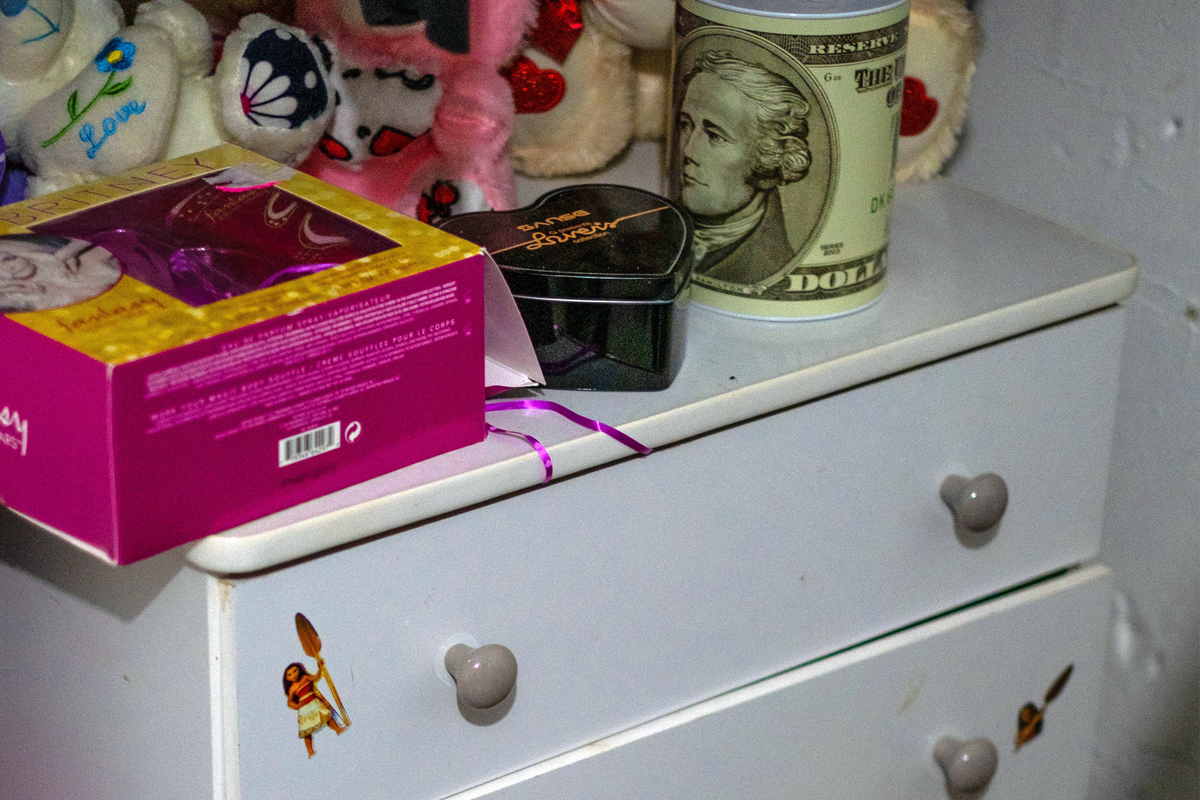

Beneath the couple’s modest collection of jackets and shirts hanging near their bed is a white dresser adorned with stickers from the Disney movie “Moana.” All the clothes inside belong to Emma.

Last October, during a break from school, Emma spent a couple weeks in Panama. It was her first time visiting her parents in their new country. A marker-decorated poster board they welcomed her with at the airport still hangs over their bed.

“It was good, sentimental, having my daughter here,” Edmily said. “It already felt like home with dad, daughter and I. We were already better. Imagine if you had been raised far from your mother.”

They keep the clothes for the next time Emma comes, hoping it will be for longer. Emmanuel doesn’t know where his future lies, but wherever he is, he said he wants to be “with my daughter, wife, all three of us.”

Before Emmanuel hops onto his motorcycle and roars onto the streets of Panama City, he slips a black polyester sleeve onto his right forearm. Appetito24 drivers aren’t allowed to show tattoos, and he needs to hide a big one: an outline of Venezuela filled in with its national colors.

“I’m an immigrant from Venezuela.” he said “It is a symbol so that when I’m an old man, I can say, ‘I got this tattoo when I left my country.'”

Venephobia

One place Viloria occasionally picks up food to deliver is En la Fonda. Its owner, Poulett Morales, calls the restaurant “100 percent Panamanian” – no Venezualan dishes.

“I want Panama to go back to our roots, no fusion,” Morales said. “I think that’s why this restaurant is famous. Because I preserved our roots.”

Morales isn’t an outlier. Her philosophy echoes a nationalistic sentiment that’s grown in recent years. In 2016, shortly following peak flows of third-wave Venezualan migrants, a political slogan appeared in Panamanian popular culture: “Panama for Panamanians.”

One flyer prefaced the phrase with a reference to popular Venezualan dishes: “No more arepas or tequeños, Panama for Panamanians.”

“What I want as a Panamanian is that if you come to work in Panama, to learn about our roots, not for you to put your roots on my country,” Morales said. “And I think that’s how Panamanians feel.”

Wendy Mow, a monitoring and evaluation specialist with HIAS, said Panamanian xenophobia is largely directed toward Venezuelans, earning it a special name: “Venephobia.” For her, it is irrational and perplexing that the same vitriol isn’t directed toward migrants from other countries, such as Nicaragua and Colombia.

On the streets in and around Panama City, Uber drivers offer a window into the state of Venephobia in the capital. Many say they have Veneuzelan friends, but others have more complicated perspectives, preferring the older business owners of the first waves to the younger laborers of the third.

Uber driver Antonio Perez said he gets frustrated with Venezuelan passengers who go on about their home country and complain about their new one.

“They talk about (Venezuela) as if it’s the eighth wonder of the world,” he said.

He said he bites his tongue and resists retorting to maintain his 5-star rating, but it bothers him. Panama has seen immigration for years, he said, but Venezuelans are different.

“I have never had a problem with any other nationality,” he said, “but Venezuelans do not have respect; they are too much for me.”

For Perez, the problem with accepting Venezuelans exists in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and elsewhere in Latin America.

“They are not loved, no one wants them,” he said.

Listen

According to Mow and a host of others in the city, the anti-Venezuelan sentiment is reflected in hostile social media posts and biased news reports. Although adults may be able to suppress their ill-will in public, their kids seem to be expressing it for them.

“One of the concerns of HIAS is that (xenophobia) is affecting children,” Mow said. “Children always say, ‘Yeah, because my mom told me, because my dad told me, that the Venezuelans are here because they want to steal our jobs.'”

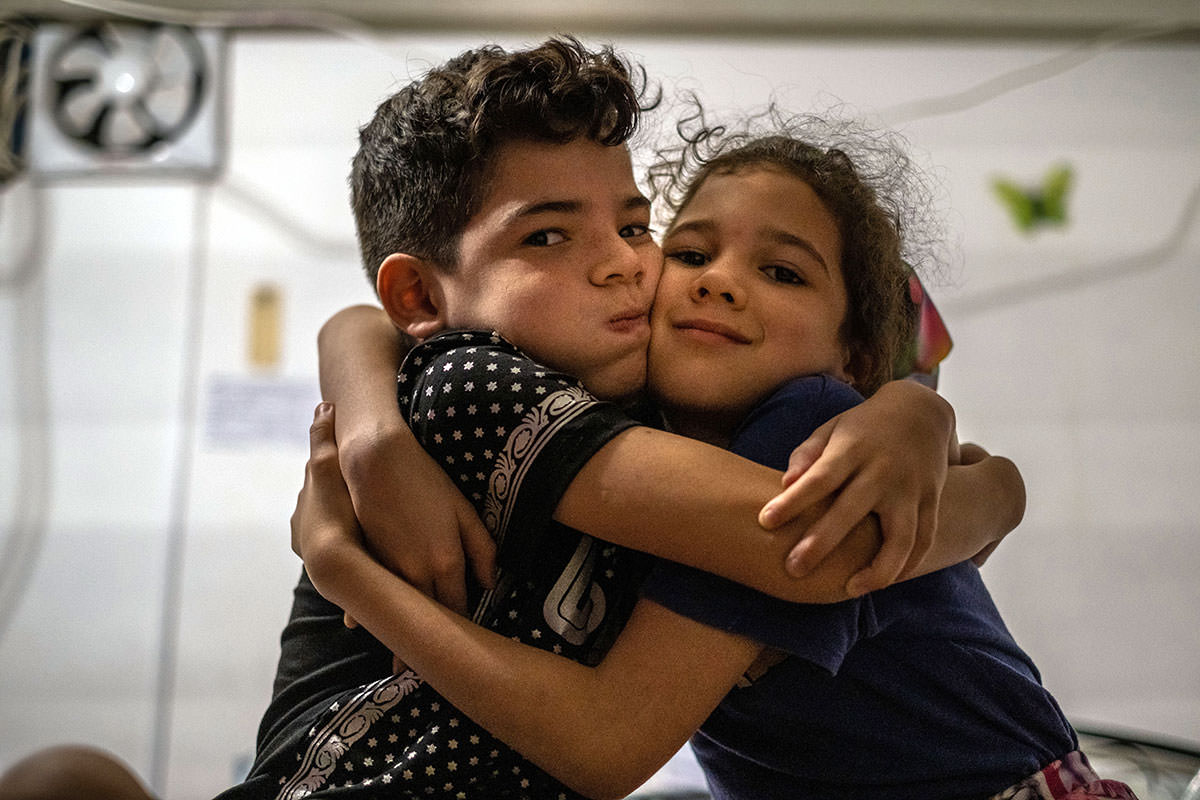

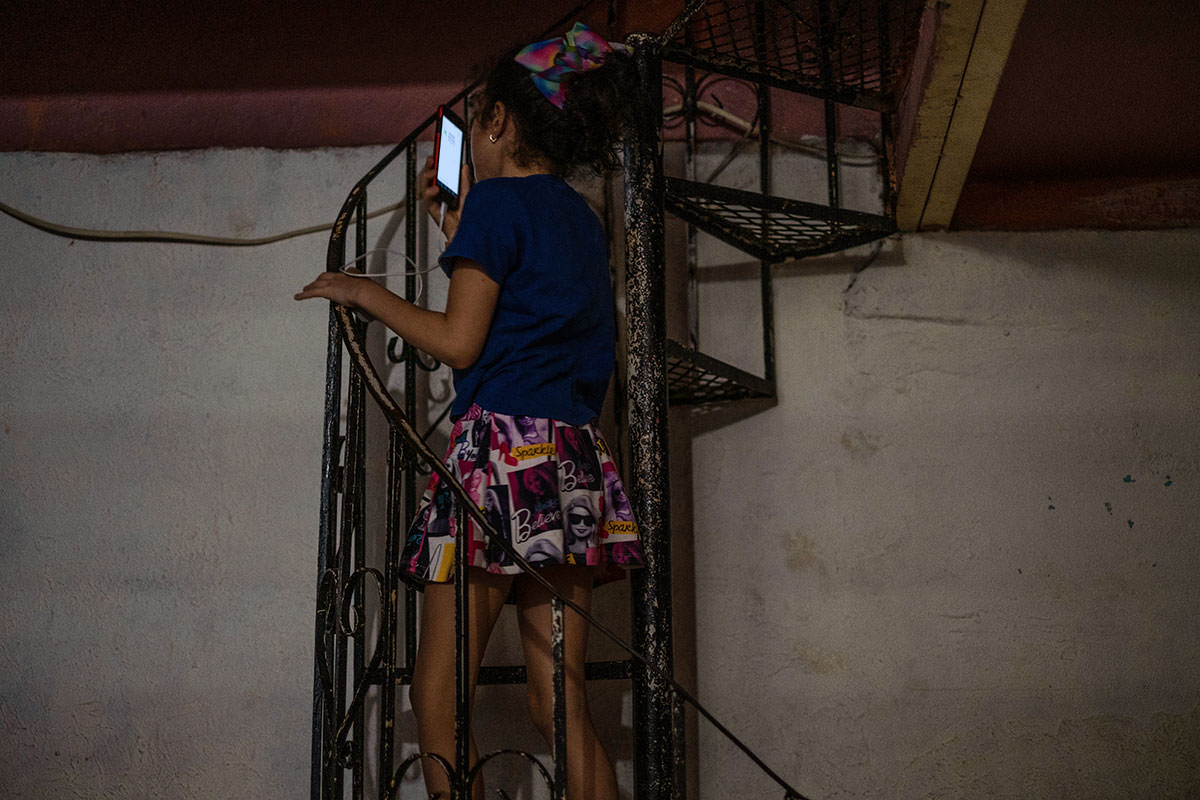

After they fled Venezuela for Panama in 2019, Nelson Diaz and his brother were joined by his brother’s wife and their two children, Antonella, 8, and Antoine, 10. To get to their room, the children climb a flimsy steel staircase. It spirals steeply as to not take up much of the main room’s precious space, and it leads to a modest loft divided into two doorless rooms – one for the adults, the other for the children.

They spend much of their time playing the video game Minecraft on the home’s only TV. Antonella’s bed sits next to a small barred window; it overlooks a street below that many travel websites deem too dangerous for tourists. She and her brother try to avoid the other kids of the neighborhood.

“The (children) from outside bother me,” Antonella said. “They say (to us), ‘The one from the house is annoying, it is the Venezuelan who should get out of here.'”

Diaz said Antonella has come home with ripped shirts and stories of getting hurt by her classmates. Like any family dealing with bullying, he said, they try to teach the children not to pay any mind to the words, but they still leave a mark.

Antonella is unequivocal when asked whether she likes Panama: “No.” She says she misses her friends and the food in Venezuela and wants to move back.

“On the street here in Panama, they have shouted, ‘Go back to your shitty Venezuelan country!'” Diaz said. “They believe we came to steal their jobs, but we are willing to do any kind of work. Waiters, washing cars – there is a doctor that now washes cars.”

In 2018, the dancehall reggaeton singer Mr. Saik stirred controversy with his hit “La Chama,” which tells the tale of a female Venezuelan immigrant in Panama who was “someone famous” in her former life. But she, like Diaz, resorts to selling arepas to get by in her new country – “a delicious thing,” the song says. But the food vending is widely seen as tongue in cheek metaphor: What she really is selling is sex.

Diaz takes the song as a joke, but he said kids at school sing the song to Antonella and call her “chama,” comparing her to the girl in the song.

“She does not understand that the song has a double meaning,” Diaz said. “We understand that we are adults, they are not.”

Somos Lo Mismo

As Mr. Saik topped charts and shot music videos in private planes, Anibal Rey toiled in unglamorous obscurity. When he arrived in Panama, he worked 80-hour weeks as a janitor and security guard. It was, he said, “a life of monotony, a life by inertia.” In his precious moments off, he wrote songs on an acoustic guitar, drawing inspiration from John Mayer’s melodies and Jim Morrison’s lyrics.

Rey, now 26, left Venezuela in 2014, just ahead of the bulk of the third wave. He’s seen Panamanian hostility increase during his years in the capital, which he attributes in part to the growing number of Venezuelans still learning how to integrate into a new culture.

“We have to adapt,” he said of his countrymen. “If you come to my house, you have to go with my rules, and if I go to your house, I follow yours. Many Venezuelans did not know how to make that change of mind: ‘I am in another country, I must behave, I have to accept to keep my mouth shut and not be critical.'”

As Rey learned to be Panamanian, he gradually gained a following and now earns a living solely from music – supported by a fanbase he describes as 80% Panamanian and 20% Venezuelan. Although there sometimes is friction between the groups in general society, they come together over his music, Rey said.

“The fans are people who know me, because they know that I am an artist and that I am Venezuelan,” he said. “Everyone is kept at peace, and they like what I do.”

With the same idea of harnessing the bonding power of music, UNHCR, the U.N.’s refugee agency, organized a late 2019 concert as a part of its Somos Lo Mismo or “we are the same” campaign.

Anibal Rey plays at an event in Panama City. Two of his three bandmates are also from Venezuela. They earn a living from playing gigs in the city. Rey writes and performs his own songs. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project) Listen

The campaign was spearheaded by Angela Florez, who said it was born out of the unfortunate realization that “Panama showed growing spurts of xenophobia and discrimination, particularly to Venezuelans.”

Like HIAS, Florez and her colleagues at UNHCR are particularly concerned with bullying in schools.

“Discrimination is growing not because of their classmates, but because of principals or teachers or even the parents of their classmates,” she said.

Although school children aren’t likely to attend night-time rock shows, their parents might be.

“The rationale behind (the concert) was that music brings everyone together,” Florez said.

To headline the show, they chose Llevarte a Marte – in English, Take You to Mars – a popular Panamanian band whose sound is described by music writers as “Latin fusion rock.” Bassist Jairo Barboza welcomes the description, saying the band loves to draw inspiration from disparate styles and cultures.

“It’s a part of being Panamanian. It’s a mix of races, cultures. There’s no such thing as 100% pure Panamanian,” Barboza said.

This ethos is part of what attracted UNHCR to the band, Florez said.

“(Somo Lo Mismo) is about helping Panamanians remember their story, in that there are no Panamanians who do not have someone in their family line that was born somewhere else,” she said. “We were a mix of cultures, and that’s what makes this country so great.”

In tracing the recent xenophobia in Panama, the members in Llevarte a Marte singled out the prominent politician Zulay Rodríguez. After a failed presidential candidacy in 2019, she earned an influential place in the National Assembly and has introduced a set of nationalistic proposals.

Venezuelans “come here to insult us, to slander us and to defame us,” Rodríguez said in a TV interview in July 2019. “They say Panamanians are lazy and that our women are fat … when you are in a country, you respect the rules of the house.”

About the same time, she proposed a bill requiring radio stations to dedicate less airtime to foreign musicians and more to Panamanian artists. Although the legislation would have benefited Llevarte a Marte, the message behind it doesn’t appeal to the band members.

“Honestly, it doesn’t make sense,” said lead vocalist David Lamboglia, adding that Panama always has been a country of immigrants – made better through foreign influence. He and his bandmates want to highlight the similarities among all people rather than their differences.

“The message (of the concert) was we are all the same. Somo Lo Mismo: We’re all the same. Regardless of the country, where we come from, or the status that we live in, we’re all human beings,” Lamboglia said.

Barboza said that although news and social media and politicians can be polarizing, music brings people together.

“Music supports people. Music is like a universal language,” he said.

Rey, the musician who left Venezuela in 2014, said his music not only brings people together, it inspires them – particularly those from Venezuela.

All across Latin America, Venezuelans are in desperate situations. Rey said for those consumed with finding food or supporting family back home, the thought of achieving your deepest dreams can feel outlandish and naive.

But despite the challenges of a crumbling society in Venezuela and becoming an immigrant, “I always looked for what I wanted,” Rey said. “So achieving it, or achieving it little by little, many Venezuelans say, ‘Wow. If he could do it, I can, too,’ both in Venezuela and here.”

Rey is recording his most recent song, “The Roots,” a sensual ode to his former home. He sings about missing the distinctive feeling of the Venezuelan wind and sun. His lyrics say it all: “The ocean here doesn’t do it for me.”

Listen

‘We miss everything’

On an afternoon with a light delivery load, Nelson Diaz took a moment to sing a traditional tune many see as an unofficial national anthem of his home country. It’s titled “Venezuela.”

“I carry your light and your scent on my skin … I carry the foam of the sea in my blood and your horizon in my eyes,” he sang. “And if one day I am shipwrecked and a typhoon breaks my sails, bury my body near the sea in Venezuela.”

Antonella stood by him in the dining room, watching with wide eyes and clapping when he finished. When the 8-year-old thinks of Venezuela, she thinks of the food, her family, and the pretty beaches. But her uncle also remembers a more sinister place.

Diaz said he was robbed more than 10 times, including twice in one day.

“One with a knife, another with a gun,” he recalled. “That was one of the moments where I messaged my brother and said I didn’t want to stay. I wanted to leave the country because I felt my life was at risk.”

According to a 2019 study by the Mexico City-based advocacy group Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice, Caracas, Venezuela’s capital, had the third highest murder rate of any city in the world in 2018.

“We had everything, and suddenly we had nothing,” Diaz said, adding that his family would be home in Venezuela if they could return. “We miss our things, our culture, the air, everything.”

Home, though, is looking as bleak as ever. The International Monetary Fund projects Venezuela’s gross domestic product for 2020 to be $62 billion. In 2014, it was $482 billion.

In May 2019, the Central Bank of Venezuela released official data for the first time since 2015. It showed rates of inflation at 274% in 2016, 863% in 2017 and 130,060% in 2018. The IMF projects Venezuela’s inflation rate for 2020 to slow to a still-staggering 15,000%.

Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, has become effectively worthless.

On his plastic dining room table, Diaz laid out a collection of credit cards and cash. Once worth more than $200, the 2,255 bolivars they represent are worth less than 1 U.S. cent.

He said he’s “very grateful to Panama for opening its doors” to him and his family, but this is not his home.

“To me, a home is where one feels welcome, where you’re allowed to grow as a human being, as a professional, where you see a future in the short and long term,” Diaz said. “And I feel here in Panama, I will not achieve (my dreams) because there are many limitations where, as a foreigner, you can’t get ahead.”

Nelson Diaz shows his Panamanian work permit, which he says cost him $1,500. Panamanian law reserves 56 professions for citizens, including pharmacist, Diaz’s former job in Venezuela. Due to this restriction and others, many skilled immigrants in Panama work as laborers. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

As COVID-19 began to sweep through Central America in March, the situation for migrants only worsened. As Panama went into lockdown, Diaz said, he wasn’t able to deliver food, leaving him broke. When he pleaded with his landlord for leniency on rent, she told him, “It’s your problem.”

Wendy Mow of HIAS said the Panamanian government has offered relief in the form of $80 per month in food, but few people – either citizens or noncitizens – are capable of jumping through the administrative hoops to get it.

Diaz said he didn’t even apply for it, thinking it was reserved for citizens.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, Panama in 2017 became the first Latin American country to require visas for Venezualans to enter. To attain one, applicants must have two forms of ID and provide “proof of economic solvency” – meaning they have the equivalent of $500 USD in the bank.

Despite such policies to discourage immigrants, an increasingly desperate situation in Venezuela continues to push them out. The increasing restrictions, Mow said, have resulted in more Venezualans traveling to Panama through the deadly jungle known as the Darién Gap.

Food is like music

As an economic negotiator for the Venezuelan government in the early 2000s, Roberto Arias saw the country heading toward disaster far earlier than most. In 2006, he became a part of the first wave of migrants, leaving for Panama City to start a restaurant called Panadería Los Venezolanos.

Arias said he had gone back to visit Caracas in recent years.

“It was not the city I used to live in,” Arias said. “It was so different. The streets were empty, people’s faces actually changed. The humor and the smile actually left their faces. I saw that and I thought ‘God, I’m glad I did what I did.'”

He said his restaurant has become a hub for Venezulans in Panama City.

“It’s like the Ratatouille effect,” he said. His Venezuelan customers tell him, “you transfer me to my childhood.”

He takes comfort in the fact that people from all places enjoy his arepas and empanadas: Panamanians, Americans, Argentinians, Canadians and Chinese alike. It brings them together.

“Food is like music,” he said. “Food is exactly like music.”

Nelson Diaz, the former pharmacist, is used to cooking empanadas as if his life depends on it. When he was 2, his father died in a car accident. To keep the family afloat, he and his five older brothers went to work on the streets selling his mothers’ fried turnovers. Now, his brothers are spread across the Americas: Panama, Colombia, Chile, United States and Canada. The last time they all were around the same table was 2012.

“I want to live in Venezuela,” Diaz said. “That is my country. I miss it, every day, every moment.”

His popular empanada business is called Marucha’s House, named after his mother. He uses her secret recipe and sells them for $1 each.

As the sun goes down on a typical Wednesday evening, Nelson finishes a fresh batch of empanadas and shouts to the children to come downstairs. The kids cram into the car with Diaz’s best friend, Amanda. Deliveries are often a group activity.

As they wind through the streets of Panama City, they blast Venezuelan songs of all styles, from all eras. They all know the words, even Antonella. The songs remind them of home.

After the day’s deliveries are made, in a quiet moment between uncle and niece, Diaz asked Antonella about the kids in the neighborhood who tease her, the ones who tell her she should go back to where she came from.

“How do you feel when they say that?” he asked.

“Bad,” she answered, and so Diaz reassured her.

“But we have each other, right?” he said. “It doesn’t matter, we have to be proud to be Venezuelan.”

Connect with us on Facebook.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]