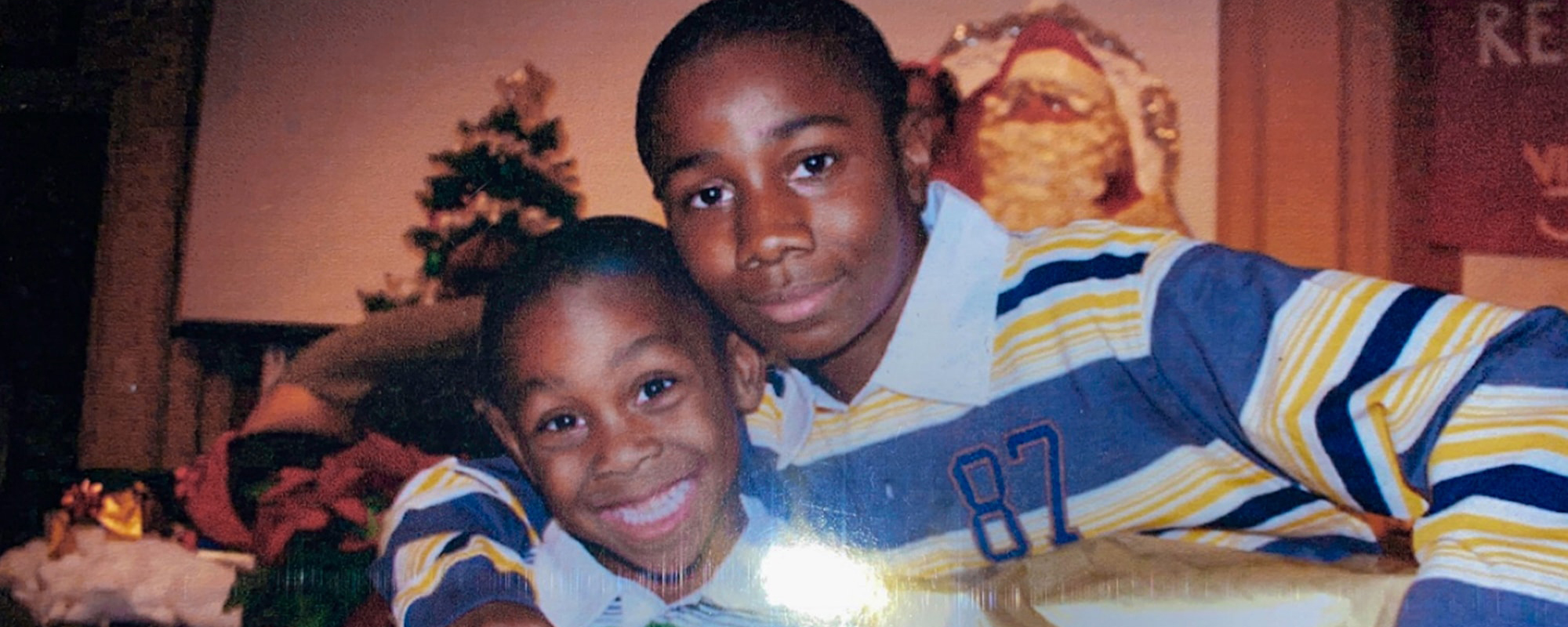

Zyion Houston-Sconiers, right, was 12 when this picture was taken. Now 25, Houston-Sconiers takes full responsibility for the robbery he committed at 17, but he wishes more people understood the life circumstances that led him to prison. (Photo courtesy of Arrogrance Wood-Houston)

The ununited state of juvenile justice in America

By Katherine Sypher and Anthony J. Wallace/Cronkite News |

As a child in the United States, justice often depends on where you live, the color of your skin, which police officer arrests you, or which judge, prosecutor or probation officer happens to be involved in your case.

Juvenile courts across the country processed nearly 750,000 cases in 2018. About 200,000 of these cases involved detention – removing a young person from home and locking them away, according to data from the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Depending on where a young person lives, a crime like simple assault or gun possession could lead to a customized rehabilitation program with help from mentors. It also could mean confinement in a group home, where kids wear their own clothes and counselors call them by their first names. Or it could mean time in a barbed wire-rimmed “prison for kids,” part of a system rife with rioting, suicide and sexual assault.

“We call it justice by geography,” said Elizabeth Cauffman, a developmental psychologist at University of California, Irvine. “Where you live determines how you’re treated as a juvenile.”

Some young offenders, including Zyion Houston-Sconiers of Tacoma, Washington, skip the youth facilities and are sentenced as adults, subjecting them to the same prosecution and prisons as older and more violent criminals.

Others, like Will Lewis from Riverdale, Georgia, are steered by police, probation officers, defense attorneys, prosecutors, judges or others toward the system’s “off-ramps” – diversion or second chance programs, based in the kids’ communities, that are designed to give them skills and improve their futures.

Today, Houston-Sconiers is inmate #368944 at the Monroe Correctional Complex in a Seattle suburb.

Lewis juggles raising his infant daughter, Carmen, working with the Brighter Future initiative at United Way of Greater Atlanta, while he looks for his dream job as an IT specialist in the aviation industry.

Will Lewis holds his baby daughter, Carmen, in his home in Riverdale, Georgia. “I want to be instrumental in her life in every way I can be, because I know I didn’t get that,” Lewis says. “I had football games, award ceremonies … and nobody that I knew was there and everybody else’s family was cheering them on. It was very discouraging.” (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie/News21)

Kids make poor decisions every day all across the country. But what happens to adolescents after their mistakes is largely a matter of luck – what Cauffman calls a “randomness” rooted in biases, beliefs and decisions of the adults who control their future.

According to Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention data from 2018, nearly 40% of Black juveniles charged with weapons offenses had their cases adjudicated – deemed responsible for their actions, most likely by a juvenile judge – and about 13% were placed in a secure facility away from home. By comparison, nearly 27% of white children facing the same charges were adjudicated and about 5% were placed in a facility.

Although they represent 14% of the country’s children age 18 or younger, Black kids account for 66% of the U.S.’s youth robbery offenses.

Lewis and Houston-Sconiers are Black, 25 years old, and both have a propensity for data and numbers. Lewis recently graduated from Middle Georgia State University with a master’s degree in cybersecurity; Houston-Sconiers earns money from day-trading stocks with the help of his wife while behind bars.

They both grew up poor, say they joined gangs to find the camaraderie and love their fractured families couldn’t provide – and both admit they made a mistake. When they were teenagers, both committed robbery and had their cases brought before an adult court.

Backed by friends, Houston-Sconiers threatened kids in his neighborhood with a gun loaded with the wrong type of bullets to hand over their Halloween candy. Lewis and some friends attacked a group of boys in a back alley, emptying their pockets in the process.

“What we call it in the streets is respect … when all it is is love,” Lewis said, referring to what the gang provided him. Growing up in poverty, he said, “your family is in survival mode constantly, so there’s no room for, ‘Hey, I love you.'”

Following their arrests, Lewis and Houston-Sconiers had life-changing interactions with the juvenile justice system. Lewis for the better, in an innovative second-chance program. Houston-Sconiers, for the worse, after he was sentenced to 31 years in prison.

Reflecting on his experience before he was granted a second chance, Lewis said, “I knew deep down in my heart that I wanted better, I just didn’t know how to get it.”

According to researchers and advocates, a mountain of evidence paints a clear picture: Detention hurts the development of young people, making them less likely to graduate from high school or find a steady job, and more likely to end up in prison as adults.

“(We) think that yelling at them and shaming them and blaming them and incarcerating them and threatening them is going to get a result,” said Adam Foss, a former Suffolk County assistant district attorney in Boston. “But really all that is doing is further entrenching their trauma and making them more violent people.”

Will Lewis was arrested for robbing a group of boys when he was a teenager in Georgia, but an innovative second-chance program kept him out of detention. Lewis, 25, now works at Brighter Future, a United Way of Greater Atlanta program. (Photo courtesy of Will Lewis)

Houston-Sconiers, 17 at the time of his crime, was the oldest member of his group on Halloween night in 2012.

“I took responsibility for the whole night because I was being a bad leader,” he said. “I’m at fault.”

In prison, Houston-Sconiers doesn’t get much sleep. He adheres to his “program”: a strict weekday routine starting at 6:30 a.m. He reads the Wall Street Journal or Forbes magazine, skips prison breakfasts of bran bars in favor of trading stocks, gives his wife a call to “make sure she made it to work.”

“It’s persistence, man, it’s not giving up on yourself or your dreams, no matter what. You have to work through the brick walls you run into, you gotta find a way around them,” he said. “You’ve got to make it through.”

He said he often stays up past midnight. He’s writing a book of advice for people entangled with the justice system. When he hears about Lewis’ story, Houston-Sconiers isn’t jealous or dismayed — he’s encouraged.

“I’m happy you told me about that man’s story. That’s more proof that rehabilitation and alternatives to confinement are effective,” he said. “I don’t know why you wouldn’t want somebody to turn out a success, rather than just throw away their life.”

Unraveling the system

Most advocates and many politicians generally agree that youth incarceration in prisonlike facilities should be reserved for rare cases, if not eliminated, and replaced by evidence-based programs dedicated to rehabilitation.

Elizabeth Cauffman oversees the Crossroads Study, a multiyear, ongoing study based at University of California, Irvine, where her team studied how the system handles “tipping point” offenses – burglary, simple assault and other medium-level offenses.

What they’ve found, she said, is that for juveniles who commit these crimes, the likelihood of being locked up is “basically 50-50. Some of those kids get probation or get some sort of diversion and some of those kids get locked up.”

“There is randomness in all states because what you have are human beings making decisions,” Cauffman said. “That just creates human error.”

Her team found that harsher sentences, such as detention, were more likely to lead juveniles to commit crimes in the future.

“The more punitive, the more harsh, the more the severe the sanction, the worse the outcome for the kid,” she said. “If you really want to improve public safety, if you really want to reduce criminal offending, getting tough is not the solution.”

On Oct. 31, 2012, Houston-Sconiers and four other boys roamed the streets of Tacoma, Washington. Armed with a small silver revolver, they approached groups of trick-or-treaters and other individuals, and stole 96 pieces of candy, a pumpkin candy bag, a red devil mask and a phone.

Houston-Sconiers was tried as an adult, convicted of robbery and given a sentence that would have kept him locked up until he was nearly 50.

Jeannie Darneille, who was elected to Washington’s state Senate just one week after Houston-Sconiers’ arrest, said she was flabbergasted to learn the length of his sentence.

Since 2012, she has spearheaded the effort to undo the legislation involved in his case and enact reforms for the juvenile justice system in Washington. She worked to unravel each element of his case and proposed new laws, including one that codified a Washington State Supreme Court decision that led to Houston-Sconiers’ release after five years served.

Shortly after he was released, however, he reoffended – Houston-Sconiers claimed he was unfairly implicated in the incident – and went back to prison. He is less than one year into an 11 year sentence for gun and drug crimes.

Zyion Houston-Sconiers, in front at right, and his co-defendant in the 2012 Halloween candy robbery, Treson Roberts, deliver cupcakes to Jason Lee Middle School in Tacoma, Washington, in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Arrogrance Wood-Houston)

For Darneille, it was important to examine the moments when the system failed Houston-Sconiers.

“Where else could we have intervened? What could we have done?” she asked. “We recognize now that he’s a kid that’s got a whole lot of hits against him and a whole expectation that any kid can pull themselves up by their bootstraps is absolutely impossible.”

In Washington, as in the rest of the country, juvenile crime is on the decline. According to data from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, nearly 2.5 million kids were arrested in 1999 and more than 100,000 were detained on any one day in a juvenile facility. In 2018, the number of kids arrested fell to nearly 730,000 and the number of detained kids on a given day dropped to just more than 37,500.

Despite the declines, the U.S. still leads the world in youth incarceration. According to data from the 2019 UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty, the United States incarcerates about 60 kids for every 100,000, the highest rate in the world.

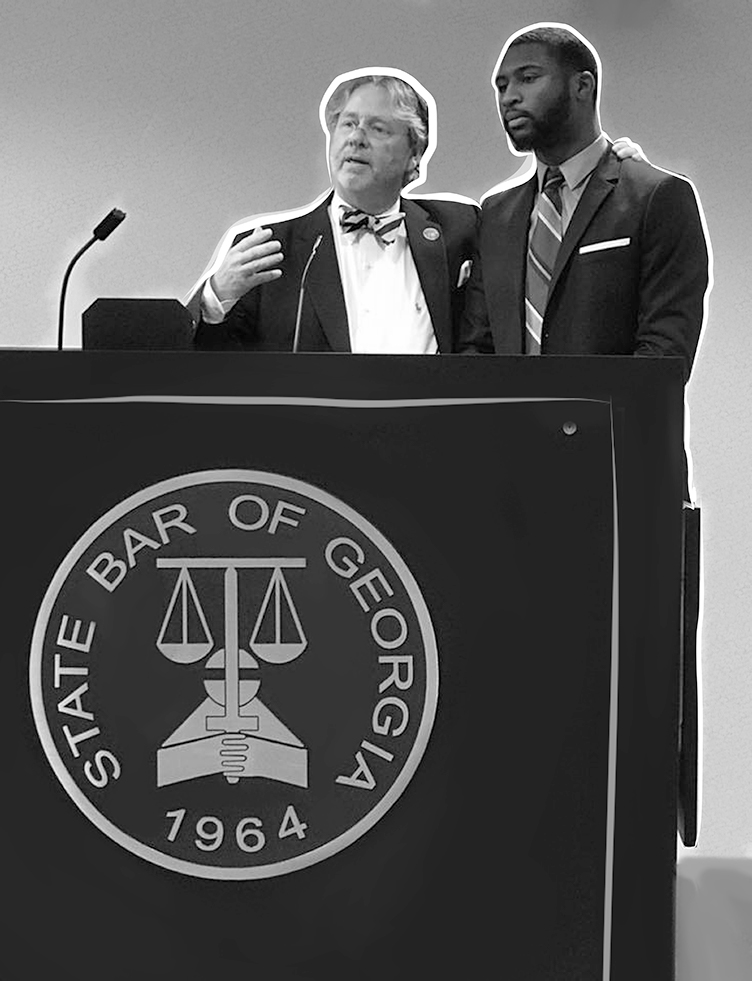

Some courts are offering alternatives. Judge Steven Teske, the juvenile judge who oversaw Lewis’ case in Clayton County, Georgia, took note of the model airplanes probation officers saw in the Lewis home and the decent grades on his report cards. He saw a future Lewis didn’t see for himself.

Teske enrolled Lewis in “Second Chance Court,” a program that offers high-risk felony offenders an alternative to detention. If Lewis and others in the program comply with the court’s requirements, which include wearing a GPS tracker for six months and cognitive behavioral therapy, they can avoid detention. The program jump-started Lewis’ academic career and he went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in aviation science and management.

According to Teske, 65% of juveniles who are sent to Georgia’s youth prisons reoffend upon release. But only 17% in Teske’s second chance program reoffend.

“I’m just trying to get them to adulthood without killing somebody else or themselves, creating the opportunity to do what the science informs me that most of them will do, and that is age out of delinquency,” Teske said. “All I’m trying to do is get kids out of the age of stupidity.”

The mind of a child

Houston-Sconiers said his mother abused him physically for more than a decade before child protective workers placed him in the foster care system, which took him through a series of short stints at several homes across Washington. Many, he said, “were only in it for a check” and put locks on their refrigerators.

Zyion Houston-Sconiers has a program he follows in prison. “It’s persistence, man, it’s not giving up on yourself or your dreams, no matter what. You have to work through the brick walls you run into. … You’ve got to make it through.” (Photo courtesy of Arrogrance Wood-Houston)

When he was 12, Houston-Sconiers began running away from his foster homes and committing petty crimes, like vandalizing city buses. From age 12 to 17, he cycled between foster homes and juvenile detention centers.

“I think I’ve only spent, like, two of my birthdays since the age of 12 … actually out,” Houston-Sconiers said. “The rest of them I’ve been incarcerated for.”

Eventually, he landed with a family in University Place, Washington.

“I was doing great, I really was. I was going to school every day, I was making my allowance money,” he said. “This was the first place I felt the love.”

But Houston-Sconiers said child protective workers involuntarily removed him from the home and returned him to Hilltop, the neighborhood where he committed his Halloween crime. He found camaraderie with the Hilltop Crips, a gang that rose to infamy during the country’s crack epidemic, and took to the streets.

A 2014 study published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences found that the brain’s decision-making centers are still wiring themselves until “the early 20s,” and while they’re under construction, young people are largely driven by a desire to bond with peers and seek novelty.

“The biggest task of adolescence is really the drive to independence,” said Sarah Cusworth Walker, Ph.D., a psychologist at the University of Washington. “So fortunately, our brains in adolescence help us make that leap by making us a little more fearless. And that means, at that time in our lives, we’re a little more willing to take risks, both socially and physically.”

Judge Teske, considered an authority on reducing juvenile crime, said he often is asked to consult with jurisdictions across the country that “divert very few kids” and “can’t figure out why their recidivist rate is high.”

“Most kids age out of their delinquency and you’re not giving them a chance to do it, for God’s sakes,” he said.

In recent years, researchers have focused on adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs – traumatic experiences in adolescence known to have a significant impact on brain development and life outcomes. They include experiencing or witnessing violence; abuse or neglect from family members; and mental illness in the household. A study by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nearly 14% of men have experienced four or more ACEs.

“I can’t tell you how many countless times I’ve been out and I’ve seen people get killed right in front of me,” Lewis said.

Adam Foss, a former prosecutor, said he graduated from law school “without hearing the word trauma.” Prosecutors, he said, are the most powerful actors in juvenile justice. They can charge a juvenile as an adult, as Houston-Sconiers’ prosecutor did, or drop the case entirely.

Throughout Foss’ career, he opposed locking up young people.

Delinquency “is very normative, boneheaded behavior,” he said. “Then at some point time you just stop. And it’s not because you’ve learned your lesson. It’s because you’ve literally grown; you’re now an adult.”

Today, Foss runs Prosecutor Impact, a not-for-profit dedicated to educating prosecutors. He said it is inappropriate in all situations for juveniles to be treated as adults.

“Some prosecutors disagree and think that there are situations where it is not only appropriate but preferred. According to physicians, psychologists, scientists, criminologists, and – perhaps most importantly – impacted communities, those prosecutors are wrong, and they are actively harming the community that they should be serving,” he said in an email.

Another Massachusetts prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Eileen Moriarty of the Cape and Islands District Attorney’s Office, said her office prosecutes “two or three” juveniles as adults per year. She said the system “is beneficial for some kids” who lack structure and resources.

“If we get to the point where we’re really not holding the kids accountable for anything, what happens when they become adults?” she asked.

Foss said that, along the way to incarceration, police officers also hold immense power, as they’re the first “domino.” They decide whether to arrest a young person and whether they start a journey down the road to incarceration.

Police Chief Dan Yourkoski in Normandy Park, Washington, acknowledges that most police officers “don’t have a good understanding” of the science of youth development.

“I can appreciate that the brain’s not fully developed until you turn 25. I get that. But I think the other aspect of that is we don’t really hold people accountable anymore like we used to,” he said. “I hate to think that we’re just coming up with a way to excuse behavior, to be frank.”

His priority is to keep Normandy Park safe, which he said has seen “an uptick in gang-related homicides – and most of the people pulling the trigger are 15 years old.”

Yourkoski trusts his personal experience as an officer more than the prevailing scientific perspective.

“I hate to say it, but there are absolutely kids, some of them are 13, 14, 15 years old, who are so hardened in their ways – I don’t know if we’re ever going to be able to reach those kids,” he said.

‘The human in everyone’

Yourkoski could have been describing Tyus Reed.

Reed, now 24, grew up in Tacoma and was raised by his grandparents because his young single mother no longer could support him.

Things were good at home, Reed said, “but when you stepped outside, that’s when you start getting into things.” When he reached middle school, he sought the “love” and “support” of his peers, he said, adding that “the cool kids are the gangbangers.”

Tyus Reed, shown at his workplace, Williams and Associates in Tacoma, Washington, credits his decision to join Wraparound With Intensive Services to his mentor, Evelyn Clark, whom he met while he was in custody for a drive-by gang shooting committed when he was 17. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie/News21)

When he was 17, Reed and his fellow gang members were riding around Tacoma when a car began following them.

It was the end of “an eventful summer,” he said, and he suspected the car was full of neighborhood rivals, so he fired at them. In reality, a couple and their 13-year-old child were in the car, and they weren’t hit. He was arrested later that night and eventually charged with assault, drive-by shooting, unlawful possession of a firearm and malicious mischief.

Behind bars for more than four years in juvenile and adult facilities, Reed said he became “disconnected from the world.” Prison guards were hostile and dehumanizing. To survive, he said, you had to be in an aggressive state of mind.

“It’s not a good place to send a developing brain,” Reed said.

Mark Steward, former director of Missouri’s Division of Youth Services, spearheaded a highly influential reform of the state’s juvenile facilities, aimed at differentiating them from the harsh prisonlike places Reed experienced.

For more than 17 years, Steward pioneered what has become known as the “Missouri Model” and transformed Missouri’s facilities from youth prisons with cells, guards and chain-link fences to smaller homes with bunk beds, colorful artwork lining the walls and a daily schedule filled with school work, therapy sessions and sports practice.

He said that he told facility employees to “treat these kids as if they’re your own kids.”

“Once they flip that switch and break down that cop mentality in the juvenile facilities – the ‘I’m the cop, you’re the kid, shut your mouth’ – and turn it more into a relationship building, the staff have really good relations with the kids and the kids know it,” Steward said.

For Reed, a positive change in his life trajectory came when he was introduced to Evelyn Clark, an advocate and youth liaison with the Washington State Health Care Authority.

“Sometimes you’ve got to come in with love,” he said. “That’s what Evelyn showed me, she showed me love.”

Clark, 31, grew up in Oakland with abusive parents who she said repeatedly told her she was worthless from the time she was 5. She was first arrested at 12 for doing drugs.

“They could’ve diverted me,” she said, but they “labeled me, because of my race, as a criminal.”

She said police told her, “You’re a Mexican, you’re sick, you need to go to jail.”

In her teen years, Clark was in and out of the system and ended up in Oregon, where a juvenile probation officer turned her life around with a simple message: “You are worth something.”

That was the first time she had heard that from an adult, said Clark, who later moved to Washington and dedicated her life to helping young people like herself.

As Reed was nearing his release, Reed said, Clark told him, “When you get out, you should do what I do.”

“I really thank her for saving my life,” he added.

Now, one year out of prison, Reed speaks to at-risk youth and, in June, Gov. Jay Inslee announced he would join a new community task force that advises Washington’s investigations of police conduct.

Clark said that many of her co-workers told her she was wasting her time with Reed.

“I see the human in everyone,” Reed said.

One morning while he was incarcerated, Reed wandered out to a common area and spotted a juvenile locked up in connection with a murder. He was eating cereal and watching the Cartoon Network series “Teen Titans Go!”

Reed clearly remembers looking at the accused killer and realizing, “That’s a kid.”

Katherine Sypher and Anthony J. Wallace are Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellows.

This report is part of Kids Imprisoned, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]