Despite an early path that led him to prison by the time he was 17, Adam Stewart found solace in boxing. In June, his heavyweight fight was broadcast for a national audience on ESPN. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart)

Fighting for his life: Once a ‘menace to society,’ boxing brought Adam Stewart peace

By Mike McQuade/Cronkite News |

PHOENIX – At 17, Adam Stewart was convicted of armed robbery and aggravated assault. Tried as an adult, he faced a maximum of 21 years. If that sounds like a lot, for Stewart it was the norm, going back decades.

“My … dad, his brothers and grandpa: prison, prison, prison, prison, drugs,” Stewart said.

But something unexpected happened when the Maricopa County Superior Court judge pronounced his sentence.

“I see something in you kid,” Stewart remembers the judge saying. “I’m going to cut you a break here. I’m gonna give you the minimum I’m allowed. But if I ever see you back in this courtroom you’re going to go away for as long as I can give you.”

Fourteen years later, Stewart, now 31, is a professional boxer, happily married and enjoying life with a wife and two daughters, Mia, 4, and Millie, 2. In June, he fought his first nationally televised fight on ESPN from the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. It was not a straight line that led him there. He is deeply grateful that the judge saw something that he could not see in himself. What is more important is that he broke the cycle of violence and incarnation that has plagued generations in his family.

Boxing saved him.

Perhaps that seems like a paradox, that an angry, violent young man could find the good in himself through a violent sport. But it is part of a larger phenomenon: the uniquely rehabilitative power of life as a boxer.

“We see stories like Adam Stewart’s all the time – a kid who’s been in trouble, or in jail, and eventually straightened out his or her life because of boxing,” said Mark Kriegel, a boxing analyst and writer for ESPN. “Back in the 1950s, the columnist Jimmy Cannon famously called boxing ‘the red light district of sports.’ It’s still that. Can be shady and disorganized, still plagued with awful judging. But it’s saved more kids like Adam Stewart than we could ever count.”

A rough start

Stewart grew up in Phoenix in a divorced family of five, an angry kid who wanted to be noticed. By 14, he was abusing methamphetamine.

“I started just doing it all the time, snorting before I go to school, (would spend) the night over at the older kids’ house,” Stewart said. “Do it all night long, stay up all night long, go to church with his family in the morning.”

He was also trying to become an athlete like his older brother Scott. He idolized Scott, already a high school football hero, whose example planted a seed for the younger brother. In the midst of freshman year at Barry Goldwater High School, Adam looked at himself, disgusted with his drug use, and quit.

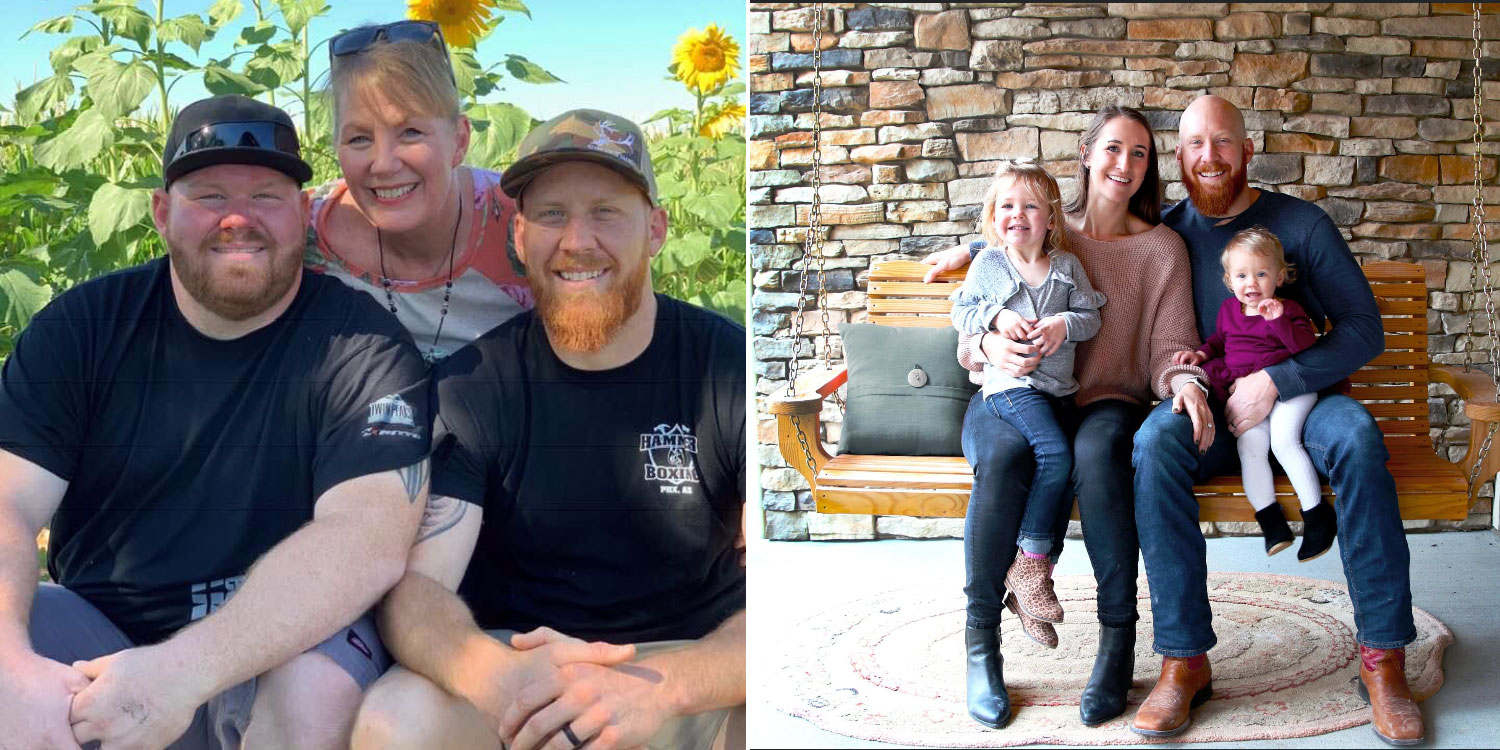

Left: Stewart (right) said he was inspired to become an athlete by his his brother, Scott (left), and was motivated to become a better person by his mother, Maria Charbeneau. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart) Right: Stewart said meeting his wife, Kathryn, changed his life. The couple has raised two daughters, Mia (left) and Millie. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart)

“I just quit like cold turkey,” Stewart said.

By his sophomore year he was living a double life. On one hand, he was working out and trying to be the football player his brother was. On the other hand, he chose to hang out with the wrong crowd, fighting on the street where he would regularly knock out men twice his age.

“I was just an angry, pissed off kid trying to get some attention,” he said. “It kept getting worse and worse and worse fighting.”

Eventually, Stewart and his crew would go on crime sprees. One weekend, they were at a party searching through a house and found guns in the parents’ bedroom.

“Monday, I got to school, six cops pulled me out of my second hour class. Next thing I know I’m getting driven down to the old Durango (Jail),” Stewart said.

Stewart spent the night at the South Phoenix facility. The next morning, the guard came to get him. He thought he was going home. Instead, he was brought to the Maricopa County 4th Avenue Jail and charged as an adult for armed robbery, robbery, attempted robbery and aggravated assault. Bail was set at $108,000. If convicted of the maximum, he wouldn’t be free until 40.

“I was a big, scary, mad guy who knocked people out. All my friends loved it,” Stewart said. “I was terrified once those doors opened at the Maricopa County 4th Avenue jail and saw the adults and their stripes.”

Stewart spent 42 days there, and was released only after his grandparents put up their house to help him make bail. He found a job at Taco Bell.

On the day of his sentencing, Stewart brought a tiny piece of paper with his prepared remarks, apologizing to the victims. He was expecting the worst: years of hard time in a state penitentiary. Instead, the judge gave him the minimum: one year in Lower Buckeye Jail and five years probation. It meant Stewart would spend his senior year behind bars and not in the classroom.

And there he was, one of the scary guys in stripes.

“We got up every Wednesday morning, bright and early, we cleaned up the streets, just as an example,” Stewart said. “Marching around to our little cadences and cleaning up trash to let other kids see us (so they would know), ‘If you’re bad kids this is going to be you chained up.'”

Opportunity surfaces

While at Buckeye, though, he earned his GED, graduating from the program frequently called “Hard Knocks High.”

“To go in there, and to be able to see him, touch him, and see him accomplish that, I was so proud of Adam for following through and making that happen,” said Maria Charbeneau, Stewart’s mother.

After serving his year, the now 18-year-old Stewart – at 6-foot-4, 240 pounds – met Sally Davis, who ran a program to help troubled teens get back on track. It seemed like an ideal opportunity to take ownership of his life.

“Let’s turn it around and do it for your damn mom that does so much for you,” Stewart remembers thinking. “(You) know she did everything she possibly could to raise us as best as she could with what she had and still working.”

Davis bought Stewart a pair of cleats and some books that enabled him to walk on the Glendale Community College football team. He was all regional conference his freshman season. The following year, a new offensive line coach, Jason Jewell, stepped into Stewart’s life.

“I’m slacking off on squats and then this big, big presence kind of came up behind me,” Stewart said.

“What the hell are you doing? Put another plate on your squat, squat lower,” Jewell told him.

Stewart reacted strongly, asking Jewell in a not-so-kind way what was he thinking.

“I turn around, look at this guy who was a 6-foot-5, 300 pounds big old bald dude just like me, but bigger,” Stewart said.

Left: Stewart received a full scholarship to Kansas' Pittsburg State but his propensity for fighting upset then-football coach Chuck Broyles, who asked him to leave. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart) Right: Jason Jewell (left), now the coach at Brophy College Preparatory, pushed Stewart when Jewell was the offensive line coach at Glendale Community College and later helped jumpstart Stewart's boxing career. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart)

Jewell, who is now the head coach at Brophy College Preparatory, pushed Stewart every day on the field and was determined to not let the athlete disrespect him. He guided the promising left tackle to another all-regional conference team, molding a five star recruit who received offers from a variety of schools, including Boise State, Oregon State and Texas A&M.

The talent was there for Stewart but the grades were not. He opted for a Division II school: Pittsburg State in Kansas.

He received a full scholarship and hoped to make a name for himself. But football was not able to anchor Stewart’s anger and the same problems began to resurface: the insubordinate, violent, street fighting character he had always been. He had a penchant for beating up baseball and basketball players so badly that they’d show up for practice with black eyes, he said. After his first season, football coach Chuck Broyles sat him down. Stewart remembers his message:

“You’re a menace to society, you need to get out of this small town. We are not renewing your scholarship.”

The only thing that kept him going was his girlfriend Kathryn. She was worth staying for, so he secured a job delivering pizzas. All he needed was a car to deliver them. That’s when his dad, who Stewart said had just burglarized a house, called.

“I’m freaking rich. What do you need?” his father said.

“A car,” Stewart said.

Stewart was an ex-convict, delivering pizzas and trying to stay afloat in Kansas. Out of the blue, he received a phone call from Glendale Community College coach Jewell that gave him an opportunity in the boxing ring.

Fit the bill

Jewell knew someone who was “looking for big tall basketball kids or football players that they could mold into boxers, and I said, ‘Well, I got you the perfect guy. He loves getting punched in the face’ and told him about Adam.”

It was at the same time that All American Heavyweights, a California-based company that seeks out talented college athletes who don’t get drafted into the NFL or NBA to try boxing, sent out recruiters. The organization was looking for athletes at least 6-3 and 220 pounds to bring back heavyweight boxing and send an American to the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. Stewart filled out an application and within a few days flew out to Los Angeles with 20 others.

Coach Henry Tillman (center) helped turned a group of athletes into boxers, including Stewart (second from left) for All American Heavyweights, a Los-Angeles based organization. (Photo courtesy Adam Stewart)

Out of the 21 recruits, only five would be selected. Their test was to shadow box in front of three judges. Luckily for Stewart, he had been in a gym working with a speed bag and throwing punches.

Three weeks went by and Stewart did not receive a call. Another week. Nothing. Finally, during the sixth week, he was asked how fast he could move to Los Angeles.

Stewart was in California within days of the call and spent the next 12 months training with boxing greats Evander Holyfield, Sugar Ray Leonard and Simon Brown.

“I (had) to take this real seriously,” Stewart said. “I just became obsessed with it, and watched the same motivational video. Just eat real clean, no drugs, no alcohol, no nothing.”

In less than two years, he went from working at Pizza Hut in Kansas to having a personal chef cook his meals on the beach in California. It became a full-time job with no expenses, just a cellphone bill and his girlfriend by his side.

“At our core, we had love and that’s really what got us through,” Kathryn said. “I will say one thing: I remember thinking when this was all going on was just how impressed by his work ethic I was.”

After the camp came to end in 2012, Stewart was one of the five finalists. One of them, Dominic Breazeale, ended up going to the Olympics while everyone else turned pro. Stewart made his professional debut four years later.

“I definitely don’t think that our love story would be what it is without boxing because it did bring me to California with him for five years where we grew so much as a couple,” Kathryn said. “Then got us to Arizona where we’ve been able to be surrounded by his family and raise our family.”

By the start of 2020, Stewart compiled a record of eight wins with no losses and one draw. For most, 2020 has been a nightmare because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but for Stewart, it has been a dream, too, because of a call received on June 16th

“Once in a lifetime opportunity fight at the MGM Grand in Vegas on ESPN. I have to risk it for the biscuit,” Stewart said.

On June 23rd, the kid who was sent to prison before he was 18, blew a promising football career and seemed to have no direction, showed on a national stage that he had turned his life around. Boxing had given Adam Stewart a second chance, all because a judge saw something, something that Stewart finally realized.

“Fighting, saved my ass, fighting saved my life,” Stewart said.

Through hard work, dedication and support from his family, Stewart walked into the ring at the MGM Hotel with boxing coach Alan Viers and good friend Justin Bales by his side, as well as dedication and support from hiEs family.

“I share his story, I share my story because everyone has a story. That’s your road to where it takes you and how you can be strong,” Charbeneau said. “Very proud of my son and the man he’s turned into. A positive story for other people to hear, learn from and grow.”

Stewart went the distance on June 23rd losing a majority decision to Helaman Olguin, suffering his first defeat as a pro.

“You usually hear about boxing using fighters, leaving them busted and broke. What Stewart did was use boxing to extricate himself from the same fate as his father and his grandfather,” Kriegel said. “If you were ever looking at a long stretch in prison, losing in Vegas goes down as a win.”

Connect with us on Facebook.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]