A horse must be 3 years old to compete in the Breeders’ Cup World Championship. All racehorses are given the birth date of Jan. 1 so their age is solely determined by the year of foaling: a young horse of either sex in its first year of life, according to the Jockey Club rule book.(Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

Why are racehorses still dying? Authorities struggle to find the answers

By William Rice/Cronkite News |

ARCADIA, Calif. – The excitement was palpable for the final race of the Breeders’ Cup. At the bell, the gates flew open to the exhortations of thousands of spectators packed into the grandstand at Santa Anita Park. Other fans, salivating over a possible big payout, gradually made their way toward the betting windows.

“Nothing beats the rush of when your horse is coming down the backstretch and you have a shot of winning that bet,” said Darrel Schwartz, a longtime bettor attending his fifth Breeders’ Cup World Championship.

Those who bet on Vino Rosso on Nov. 2 won big in the $6 million Cup Classic race, but the elation at Santa Anita was short-lived that day.

Near the end of the race, commotion broke out as green curtains were rushed onto the track, surrounding Mongolian Groom, who had seriously fractured his left hind leg. News media were shooed off the track to prevent images of the suffering 4-year-old thoroughbred, who later was euthanized, officials confirmed.

Mongolian Groom was the 37th racehorse to die at the Southern California racetrack since December, tying the park record, which had been set the previous year. More thoroughbreds have died at Santa Anita than any other racetrack in the country.

What’s behind these deaths isn’t clear, but authorities are looking at track conditions, the length of the season and performance enhancing drugs.

Weeks after the Breeders’ Cup, leading horse racing organizations announced the formation of the Thoroughbred Safety Coalition to address safety concerns through reforms to medical, operational and organizational issues in the sport, the Los Angeles Times reported in November.

Before the race, officials had announced a three-step process called the maintenance quality system used at many top racetracks to ensure the track surface is in the best possible shape.

“It starts with a design review of the racetrack, its surface, checking of grades and reviewing equipment,” said Michael Peterson Racing Surfaces Testing Laboratory. “Prior to having horses on the track, testing is done. Ground penetrating radar is used to inspect the base. Biomechanical base is used to gather all the other measurements, and then there is a review of all the equipment. The third step is the daily monitoring that is done by track personnel.”

After each race, horses are met by trainers who wipe them down with water and do a preliminary check for injuries. (Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

Horse injuries are frequent in racing, and second chances aren’t common. Nationwide, almost 10 horses a week on average died at American racetracks in 2018, according to the Jockey Club’s Equine Injury Database.

Although racetracks vow to inspect and improve track conditions, federal legislators have raised concerns about horse treatment and drug use.

According to track officials, before a horse runs its first race, it undergoes bone remodeling, mental conditioning, hoof and respiratory care, and is put under careful observation.

“We check horses prior to training if we have concerns about their health and welfare,” said Dr. Dionne Benson, chief veterinary officer for the Stronach Group, which owns Santa Anita. “We have checked 900 horses since the reopening of our track. Those 900 horses are responsible for over 1,500 examinations.”

The two-day Breeders' Cup at Santa Anita Park had an on-track attendance of 41, 243 on Nov. 1 and 67, 811 on Nov. 2. (Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

Beyond life and death, the stakes were particularly high at this year’s Breeders’ Cup. The final and most important race of the day, the Breeders’ Cup Classic, offered a $6 million purse. Earlier races added $25 million to the take.

Despite the ongoing equine deaths, the appetite for betting hasn’t diminished, and off-track records continue to be broken. The total money wagered in this year’s Breeders’ Cup races topped $174 million, the highest since the race began its current two-day format in 2007.

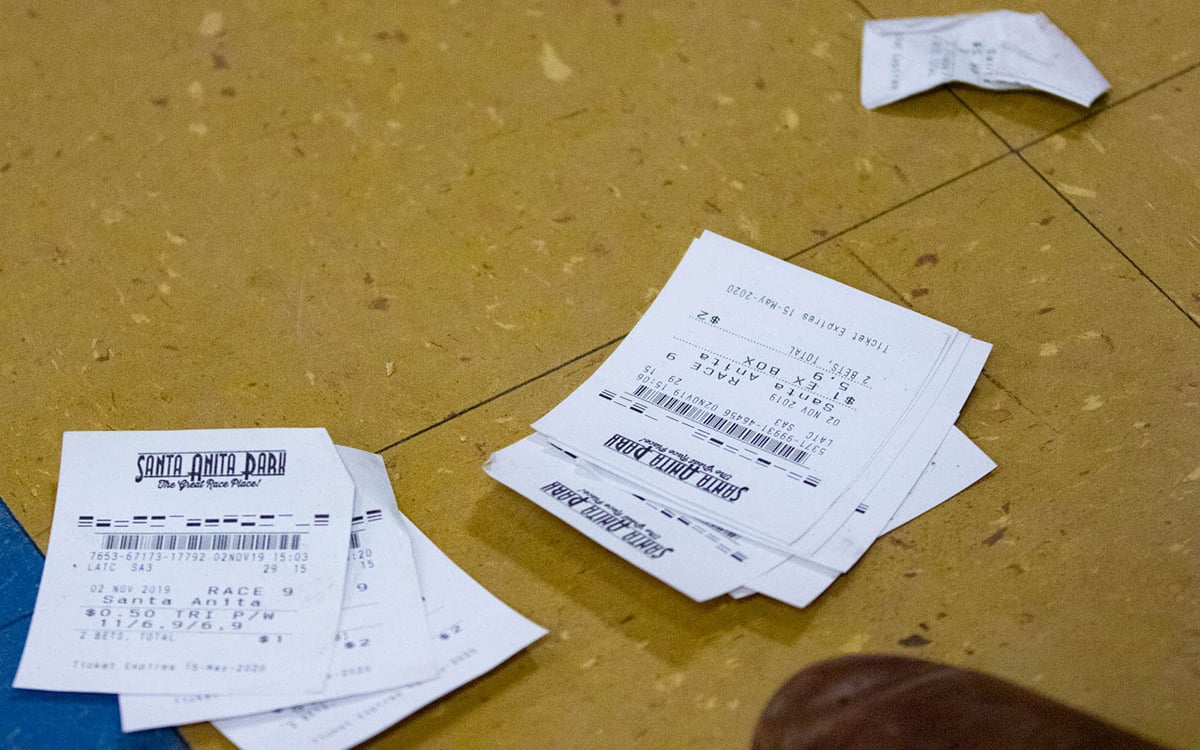

During the races, the grandstand floor was littered with betting slips for horses that didn’t finish in the money. As one race ended, bettors rushed to the windows to place their next bet in hopes of better luck or hitting another winner.

Viewing rooms are strewn with discarded betting slips after the last Breeders' Cup race. Fans around the country were able to vote through an online wagering app called TVG, the official wagering partner of the Breeders' Cup World Championship. (Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

Since the 37th equine death of 2019, activists and politicians renewed calls for Santa Anita Park to be shut down.

“Despite increased scrutiny and additional measures that have been put in place, the horse racing industry was unable to make it through a single weekend without a critical injury and euthanized horse,” U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., said in a statement days after the Breeders’ Cup races.

In June, Feinstein had called for “horse racing to be suspended at Santa Anita until it could ensure the safety of horses would be protected.”

Santa Anita went through a brief 24-day closure in March, when the death toll reached 22 and track management decided to shut the track temporarily.

The Horseracing Integrity Act of 2019 was introduced in March and, if passed, would ban diuretics that are used on race days to force horses to lose water weight. In other countries, race-day medications are banned.

Other politicians have echoed Feinstein’s concerns. In May, other senators introduced bipartisan federal legislation to limit drug use in horses. The bill faces steep opposition from Churchill Downs, a historical racetrack in Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s home state of Kentucky, Reuters reported.

California did not wait for federal action. In June, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed new rules into law. SB 469, which was approved unanimously by the Legislature, allows state officials to suspend or shut down horse races with little notice.

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, said in a statement after Santa Anita’s 37th death, “The racing industry must make a choice between doing right by the horses or shutting down forever.”

The sport is overseen by independent state regulators at the California Horse Racing Board, which elected new leadership last month. In his first meeting, Chairman Gregory Ferraro said “the days of permissive medication are over,” and he pledged to “gradually eliminate medications and keep them away from racing and training.”

One challenge for regulators is that use of drugs in horses can be masked.

“The recommendations made addressed whether therapeutic medications are masking not only the ability to examine horses prior to racing, but the restrictions of medications in training as well,” Dr. Rick Arthur, equine medical director for the California Horse Racing Board, said in an interview.

The 2019 Breeders' Cup showcased 14 races on Nov. 1 and Nov. 2 at Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, California. It was the 10th Breeders' Cup at Santa Anita since the series began in 1984. (Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

There are competing theories about why horses have been dying. Some blame track conditions, others blame temperate climates that allow long racing seasons and nonstop training. Others point to drugs used to improve speed.

In 2000, Santa Anita had synthetic turf. The racetrack had less than 1 death per 1,000 starts in that time frame. Since the dirt went back down in 2009, the rate of deaths per 1,000 starts has not been lower than 2 and has risen to 2.9 deaths. According to the Jockey Club, last year there were 1.68 horse deaths per 1,000 starts on average nationally. This racing season, Santa Anita’s total was 2.04 deaths per 1,000 starts.

“We have not ruled anything out,” Benson said, “nothing is off the table, we are looking into a number of things, including the potential to bring synthetic back. What sets us apart from any other event is the tremendous amount of care and transparency that goes into a Breeders’ Cup.”

The Breeders' Cup runs the American classic distance of 1¼ miles, on dirt. The Breeders' Cup Classic was run on a synthetic surface in 2008 and 2009. (Photo by Erica Morris/Cronkite News)

According to the New York Times, Justify, the most recent horse to win the Triple Crown in 2018, failed a drug test at Santa Anita one month before his first Triple Crown race, the Kentucky Derby.

If the sport’s rules were followed, Justify would not have been allowed to run in the Derby, making him ineligible for one of sports greatest achievements. Justify went on to become the 13th horse in the past 100 years to win the Triple Crown, and his breeding rights sold for $60 million.

Turf Paradise in Arizona, a lower tier racetrack with smaller purses, attendance and race frequency, has seen similar issues with deaths of thoroughbreds. There were 50 deaths related to racing, training and nonexercise in the 2017-18 racing season, according to a state report.

The issue has national reach, and answers have been elusive as to what is causing it, or what the solution may be.

For now, the deaths have stopped because the season is over. But the new season will begin Dec. 26 and finish June 23, 2020.

Connect with us on Facebook.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]