Builders of the Stonoview development on Johns Island, near Charleston, South Carolina, are required to build retention ponds to store rainwater and prevent flooding. (Photo by Ellen O’Brien/News21)

Developments in disaster-prone areas mean big bucks for builders but can put homeowners at risk

By Anna Huntsman and Jake Steinberg/ News21 |

ELFIN FOREST, Calif. – Elfin Forest is named for the miniature trees that blanket the surrounding ridgeline. The terrain acts like a wall, which has until recently prevented suburban San Diego from sprawling into the bucolic valley.

The town, home to 800 people and 300 horses, bills itself as “A Rural Community.” It’s accessed by a single winding two-lane road. When the valley catches fire, as it does periodically, that road is the only escape route. Residents will soon share it with 700 new neighbors.

“We’re already at maximum density when it comes to evacuation,” said JP Theberge, chairman of the Town Council. “This is a catastrophe waiting to happen.”

The U.S. has spent more than $500 billion over the past five years cleaning up after a spate of record-breaking hurricanes and wildfires – climate-related disasters the government expects to become more frequent and more furious. Federal firefighting costs now consume more than half of the National Forest Service’s budget. The National Flood Insurance Program is $20.5 billion in debt. Critics say these programs have subsidized risky land-use choices for decades, and now the bill is coming due.

Yet, from coast to coast, homes continue to go up in floodplains and areas frequented by fire. An emboldened alliance of experts, environmentalists and concerned citizens is pushing back against business-as-usual development.

After consecutive major floods in 2015, 2016 and 2017, Charleston, South Carolina, residents are calling for the city to prevent a man-made disaster in its low-lying suburbs. Builders are filling in the wetlands of nearby Johns Island, where the city has approved nearly 2,000 housing permits since 2015. In a neighboring suburb, overdevelopment was linked to flooding that forced the city to buy out homes and temporarily ban new construction there.

In the next 15 years, more than $63 billion in real estate in coastal cities such as Charleston, Miami and Galveston, Texas, will experience chronic flooding, according to a report on sea level rise released last year by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“This whole practice of development that’s going on right now is dangerous and it’s putting people at risk,” said Phil Dustan, an expert in rising sea levels who has studied Charleston’s topography. “It could create a (Hurricane) Katrina-type situation with housing developments.”

Local governments don’t have the incentive or, often, the power to stop risky development. When homes are destroyed, taxpayer dollars often cushion the blow. Developers exercise immense political power, especially in growing cities where housing is needed. People want to live in these areas.

“As a society, we really like living near water. We love living in the wildland urban interface, in the mountains and we love nature, and these are the places in particular where the disasters are more prevalent,” said Leslie Chapman-Henderson, president of the Florida-based Federal Alliance for Safe Homes (FLASH). “Should we be dredging up sand to build those places back up? Or should we just acknowledge that we shouldn’t put structures there?”

Two communities on opposite sides of the country, one plagued by fire, the other by flooding, exemplify the precarious politics of building in disaster-prone areas. In San Diego County and Charleston, as elsewhere, experts warn that tomorrow’s disasters are being built today.

California: ‘We call it the death trap’

The 2014 Cocos Fire in Harmony Grove took everything from Lali Mitchell: Her father’s writing from the 1940s, her son’s vintage Marvel comic book collection, the 100-year-old oak her kids played under.

“My mind was just pulverized,” she said. “It’s so big that you just can’t cry about it. It’s just gone.”

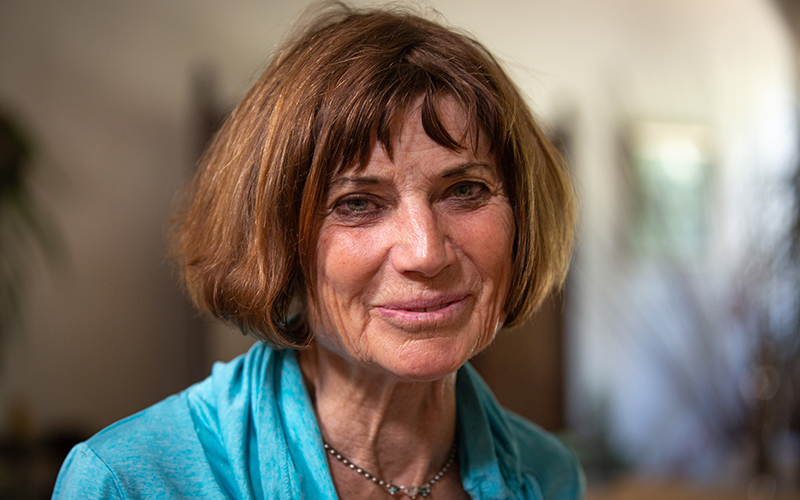

With flames at her back, Mitchell, 77, escaped by way of the neighborhood’s single road. Fire afflicts Harmony Grove regularly, and Mitchell has lived through many blazes since moving there in 1976.

But a recently approved housing project along her only escape route could put more than 400 additional cars on the road during an evacuation. If it’s built, Mitchell said, staying won’t be an option.

Lali Mitchell‘s first home in Harmony Grove, California, where she had lived since moving to the area in 1976, was destroyed in the 2014 Cocos Fire. She said the fire destroyed tens of thousands of dollars worth of art, as well as family mementos, such as her father’s typewriter. “She was her own beautiful thing,” Mitchell said of her burned house. (Photo by Kailey Broussard/News21)

“There’s no way you could be safe here,” she said. “We’re terribly concerned with what they’re creating. We call it the death trap.”

The project, called Harmony Grove Village South, represents a fraction of the more than 10,000 homes due to be built in the riskiest fire-prone highlands of San Diego County.

As in other metro areas across the nation, the cost of a home in San Diego County is soaring. The median home price is $590,000 — double the national average — and the county is 100,000 housing units short of its 2020 goal.

“We need affordable housing. And we need to better protect the region from our greatest natural threat – wildfire,” Dianne Jacob, chairwoman of the county board of supervisors, said in her 2019 state of the county speech. “We’re facing a conflict between shelter and safety, and we must find some balance in this battle.”

But recently, housing – and those whose business is to build it – have been winning. County supervisors have approved a steady stream of projects that require amending the county’s general plan, which prioritizes growth in the urban lowlands to keep it out of rural areas with limited infrastructure and severe fire risk.

Amending the plan usually increases the number of homes developers can build, which clears the way for projects like Adara at Otay Ranch. Approved in June, the project would place more than 1,100 homes in foothills that have burned every seven years on average since 1950.

Developers argue the homes will be built to the latest fire code standards and surrounded by land stripped of fire-fueling brush. State law requires developers to prepare an evacuation plan demonstrating how residents will be able to get out.

“California has certainly seen a number of devastating fires, primarily in communities built long ago,” said Borre Winckel, president of the Building Industry Association (BIA) of San Diego. “Our fire-mitigating development standards and building codes have necessarily evolved.”

However, recent severe, wind-driven fires have raised questions about the limits of fire safe construction.

“You can have the most fire safe community on the planet. When a fire is coming through at a thousand degrees or more, I don’t care what you’ve done to your house,” said Char Miller, a professor of environmental history at Pomona College.

In 2008, California passed a set of stringent building codes for high fire hazard areas. In last year’s deadly Camp Fire, nearly half the homes built after 2008 burned anyway. Miller said building homes this way is a smart thing to do, but it presents a problem: “It’s also a way by which people fool themselves that if doing this, you will be OK.”

The number of homes commingling with wilderness is expanding across the country. One in three homes in the U.S. now are in areas at increased risk of fire. The more people living in these areas, the more likely a fire will break out, said Alexandra Syphard, a fire ecologist for the Conservation Biology Institute.

“In an area with very few people, you have very few fires, because people cause all the fires,” she said.

Even in areas with ample housing, local decision-makers face pressures.

“Every city hall and every county supervisor knows that one of the tickets to their political success is to greenlight development because the developers are the key factors in funding their campaigns,” Miller said.

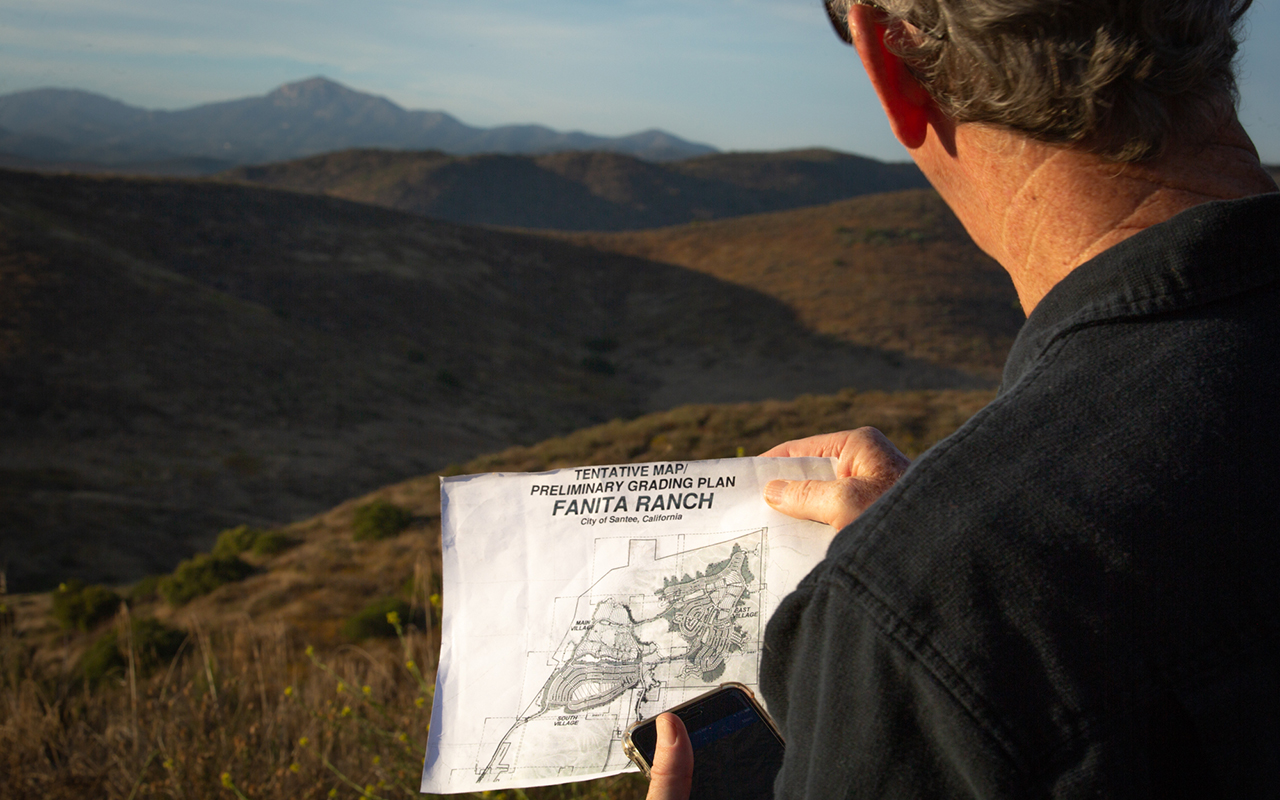

Van Collinsworth, a former firefighter with the U.S. Forest Service, checks the proposed layout of Fanita Ranch, a development approved in Santee, California. Fanita Ranch had gone back and forth between planning and legal battles for about a decade. It initially was approved in 2007, but its environmental impact reports were declared inadequate in 2013. (Kailey Broussard/News21)

Developers and real estate interests often donate liberally during election years, and local politicians often take money from builders whose projects hinge on their approval.

When a developer is in a position to make a billion dollars or more from a single project, there is little limit to what they’re willing to spend, said Stephen Houlahan, vice mayor of the San Diego suburb of Santee. “There are dark-money forces, through political action committees, that do become involved in elections on behalf of their interests.”

The BIA of San Diego spent at least $76,000 in support of Santee’s council members last election. HomeFed Corp., a BIA member, is proposing a nearly 3,000-home project in the hills above Santee – the hills that were scorched in the 2003 Cedar Fire.

“Facts are facts, science is science, and the science says that that place is going to burn,” said Houlahan, who opposes the project. “Everyone who’s grown up in this city knows it.”

Nonetheless, the project would be a financial gift for Santee, delivering a recurring tax windfall of $5 million, according to a report by a consulting group hired by the city.

The prospect of additional tax revenue is a common incentive for cities to approve more housing, according to Gregory Simon, an expert in human-environment interactions at the University of Colorado Denver.

“Why does the fire rage on and become so costly and injurious and even deadly? That’s almost always a social thing,” Simon said. “That’s because all of our stuff is there. That’s really the problem, and so we really should be questioning that in the first place.”

A recent report from Gov. Gavin Newsom said California should “deprioritize” new development in areas that burn. Three in four Californians now say the government should restrict development in high-risk areas, according to a Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll released in June. But no laws have been passed to keep homes out of harm’s way.

The communities of Elfin Forest and Harmony Grove are suing the county over Harmony Grove Village South and another housing project that together would add more than 700 homes along their eastern escape route. Dense development on the western side of the valley led to major backups during the Cocos Fire five years ago.

“People were stuck for an hour sitting in traffic because you had all the side streets coming out into the main street and they were all backed up,” Theberge said. “That raised a lot of concerns about how viable is evacuating in a fire situation.”

Mitchell has thought about where she’d go if Harmony Grove Village South is built, but she’s counting on the lawsuit to stop the project.

“I think the only thing in our favor is that last year was such a terrible fire with the Paradise Fire,” she said. “We really need a heads-up of a sane way of handling fire safety and not building in these areas that are so close to natural habitat.”

The hills of Santee overlook Weston, a housing development approved by San Diego in 2013. Longtime fireman Van Collinsworth said the houses’ close proximity to one another pose a fire risk. “If one ignites, another is likely to ignite,” he said. (Photo by Kailey Broussard/News21)

South Carolina: High stakes in the Lowcountry

In Charleston, a booming manufacturing and tech economy has transformed the city from a Civil War tourist destination into a sprawling coastal metropolis. Twenty-six people move there every day.

The city’s boundaries have grown beyond its historic peninsula. Over the past few decades, development has filled in the low-lying wetlands. Johns Island, a historically rural area west of downtown, is the latest front.

“I’d say the past six to eight years, things have really been changing,” said Dolores Payne, a longtime resident of Johns Island.

Payne’s parents once owned nearly 50 acres surrounding the plot where her tall house sits among century-old oak trees draped with Spanish moss. In 1958, they sold most of the marsh that couldn’t be farmed and kept 5 acres of the highest ground, where Payne still lives.

Dolores Payne stands on land once owned by her parents on Johns Island, South Carolina. The low-lying marshes and trees are being replaced with fill dirt and rows of suburban homes. She still lives in the home her parents built, which is surrounded by ancient oaks. (Photo by Ellen O’Brien/News21)

Now, the ancient trees and open space that once distinguished her family’s former property are no more. The lowland has been annexed into the city, which allows higher density development. Lush woodlands already have been razed.

The project, named Stonoview for its proximity to the Stono River, will include nearly 400 homes when complete. Johns Island residents have opposed such dense developments out of fear that they will worsen the flooding.

Like many coastal cities, Charleston can flood even in high tides. Known as the Lowcountry, the area has experienced more intense and more frequent flooding in the past several years: a 1,000-year flood in 2015 and hurricanes in the two years after.

For some, those disasters weren’t entirely natural.

After getting flooded in three consecutive years, a church in the neighboring suburb of West Ashley funded a study of the region’s watershed. The analysis revealed overdevelopment made flooding worse for people downstream. The culprit: storm runoff. Builders used fill dirt to raise new homes to the city’s elevation requirement, but the artificial material doesn’t absorb water like porous organic topsoil.

When the land is built on, it becomes impervious, said Norm Levine, geologist and director of the Lowcountry Hazards Center at the College of Charleston. “This can force water into other areas that were not originally having water problems.”

Fill, which is composed mostly of crushed rock, sand and clay, allows developers to build homes on land that has long been considered too risky.

“The developers are pushing the envelope and really endangering whole areas,” Charleston councilwoman Carol Jackson said.

The use of fill dirt in floodplains came under scrutiny after Hurricane Harvey inundated Houston neighborhoods. Nearly 400 homes in Harris County have been bought out, with 1,100 more recently approved.

In June, Charleston closed on a buyout of about 40 homes in West Ashley and plans to turn the land into greenspace.

Charleston, South Carolina, this summer bought out about 40 townhomes in the neighborhood of West Ashley. The area has flooded multiple times in recent years; the city plans to turn the land into greenspace. (Photo by Ellen O’Brien/News21)

“Unfortunately, we can’t go back and change the past,” said Mark Wilbert, Charleston’s chief resilience officer. “We didn’t have the science and we didn’t have the engineering technology that we have today … but going forward, we really need to make sure we don’t make mistakes.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recommends coastal communities require a permit to use fill dirt. Many coastal counties do, including Charleston County. But the city of Charleston doesn’t.

“We’ve had a foot of sea-level rise in the last hundred years. Of that sea-level rise, half of that has occurred pretty much in the last 25,” Levine said. “There are a lot of rules, laws, regulations that now need to be looked at and understood with this new paradigm of sea level built into them.”

Other Atlantic Coast cities share Charleston’s sea-level predicament. According to data analyzed by Climate Central, the 25 most vulnerable U.S. cities are on the Atlantic, with most of them in Florida.

But flood maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency don’t account for rising seas. And the agency’s National Flood Insurance Program offers cheaper insurance to those who live in floodplains, which critics argue incentivizes building homes in flood-prone areas.

The Stonoview development is one of many in Charleston, South Carolina's fast-growing suburbs that used fill dirt to elevate homes above the floodplain. (Photo by Ellen O'Brien/News21)

“Emphasizing affordability has led to premium rates that in many cases do not reflect the full risk of loss and produce insufficient premiums to pay for claims,” said a Government Accountability Office report released in March. “In turn, this has transferred some of the financial burden of flood risk from individual property owners to taxpayers as a whole.”

Federal privacy laws make it difficult for new homebuyers to know the full flooding history of their house. Newcomers flocking to Charleston could be unaware that “what they’ve just bought into is a very artificial environment that’s been created by the developers and encouraged by the city that ultimately is going to fail them,” said Johns Island resident Rich Thomas said.

A report released in July from Climate Central found homes in coastal states are being built on land vulnerable to rising sea levels at faster rates than those built on safe land. Charleston is one of 24 cities that have allowed at least 100 homes to be built in at-risk zones since 2010.

State law allows property holders to do with their land as they want as long as they follow building and zoning laws.

“Once the house is sold, [the builders] are out of the equation. When the cost comes along, who’s paying it? The homeowners through their deductible and their insurance company,” said Chapman-Henderson, president of FLASH.

Charleston will release new regulations for development in the coming months, but projects approved beforehand, including the 240-home River Run project on Johns Island, can continue to follow the old rules.

“Forget about the fact that that area holds water when we get serious rainstorms and tropical storms,” said Dustan, the sea-level expert. “Forget about the fact that we’re very vulnerable to storm surge. They don’t seem to give a rip about that at all.”

Johns Island residents continue to challenge development at City Council meetings, hoping their community won’t become the new West Ashley.

Payne intends to stay on the land where she grew up, despite the Stonoview development along her property line.

“I will never leave,” she said. “Even if I’m the last oasis in this neighborhood, I will be the last. They’ll say, ‘That crazy old lady with those oak trees.’ I’m not going anywhere.”

News21 reporters Kailey Broussard and Ellen O’Brien contributed to this report.

Kailey Broussard is a Donald W. Reynolds Foundation Fellow, Anna Huntsman is a Diane Laney Fitzpatrick Fellow, and Ellen O’Brien is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation Fellow.

This report is part of State of Emergency, a project on disaster recovery produced by the

Carnegie-Knight News21 program. For more stories, visit stateofemergency.news21.com.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]