Yenife Alexandra Carmona Rieracda, 23, and her 5-year-old daughter, Yoliannys, traveled two months to get to Lima. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Even as they adapt to life in Peru, Venezuelans dream of returning home

By Miranda Cyr/ Cronkite Borderlands Project |

LIMA, Peru – Sara Marianys Soto Duque and Yenife Alexandra Carmona Rieracda are young mothers trying to earn money to support their families.

Soto, 26, and Carmona, 23, are two of the more than 700,000 Venezuelans now living in Peru.

Soto arrived in October 2018 after leaving her family, including her 2-year-old son, behind in Venezuela. Carmona arrived in early March with her three children, boyfriend, cousin and uncle.

Although the two women have had different experiences in their journeys to Lima, they both have the same end goal: to return to Venezuela as soon as they can.

“I want to close my eyes and open them and be in my country,” Soto said.

Sara Marianys Soto Duque looks at photos of her family. She plans to return to Venezuela as soon as the economy improves. (Photo by Miranda Cyr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Similar sentiments were expressed by many Venezuelans in Lima who were interviewed by Cronkite News reporters. But most also said they have begun to adapt to Peru’s cultural and societal norms, which are different from those in Venezuela despite a common language.

Some – hopeful that Venezuela will rebound from its years-long economic and political chaos – predicted their stay in Peru will be short. Others aren’t sure Venezuela will be stable anytime soon.

Professor Carlos Eduardo Felix Aramburu, who specializes in migration at Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, said Venezuelans present a case of “push migration,” as they have been forced to leave their country due to the crumbling economy and chaotic political climate.

“People are leaving Venezuela because they just can’t stand the living conditions there, not only the lack of liberty, but basically a lack of means to survive,” he said.

Peru’s welcoming approach to the migrants has been a success so far, Aramburu said, without mass xenophobia or backlash. But the strains are showing.

“The open door policy has been an effective one,” Aramburu said. “But of course, my concern is that there’s a limit to the number of people that our economy can absorb, and that certainly will be a problem in the near future.”

Aramburu believes that if Venezuelans remain in Peru for more than a year or two, the majority will stay, despite their dream of returning home.

“History and theory shows that if this is not solved and Venezuelans begin to incorporate themselves into the social network in Peru,” he said, “it could be harder and harder for them to return. … My prediction would be that the longer the crisis, the less likely it is for them to return.”

But integration may encounter some speed bumps.

“Our style of living, our personalities, our characters are different. It’s something I realized just when I went back to Peru in the last year and I talked to Venezuelan people,” said Gabriela Dongo Arevalo, an English professor at Pontifical Catholic University who also is a graduate student and Spanish instructor at Arizona State University. “Our history is alike, but our lifestyle, our way of living, is different.”

Although Spanish colonial influences are felt in both Peru and Venezuela, she said, the two countries in recent years have been heavily influenced by other cultures. Peru’s main influence comes from the Andean civilizations, and from Italian and Japanese immigration, while Venezuela’s most prominent influences come from Caribbean and African cultures.

“I think there are more things that are different than similar,” Dongo said.

Igor Olsen, a filmmaker, emigrated from Peru to Venezuela in his early 20s during the crisis of the 1980s and ’90s, when the government in Lima sought to wipe out Marxist guerilla groups. Olsen stayed in Venezuela as he raised a family and became accustomed to life there but returned to Peru when Venezuela’s economy soured.

Filmmaker Igor Olsen left Peru during the civil unrest of the 1990s. He lived in Venezuela and only came back two years ago when the economy began to falter; he, too, wants to return to Venezuela. (Photo by Miranda Cyr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

From Olsen’s perspective, society in Peru is much more stratified by class and race, which was one factor that played into wanting to stay in Venezuela. He, too, plans to return to Venezuela once the situation improves.

Venezuelan blogger Santos Guerra, expressed similar sentiments about the differences he has observed in his travels between the two countries. Although Peru is a beautiful country with many intriguing aspects, he said the societal differences are still a shock to him no matter how many times he leaves and enters the country.

“Since I have come many times to Peru, I know how difficult it is and how shocking the Venezuelan society versus how the Peruvian society is,” Guerra said. “The Venezuelans (are) very social, very extroverted, so you stand in a corner next to a stranger, and you will begin to tell them your problems that are your personal problems. … It is part of us. But the Peruvian here is quite distrustful. He is generally distrustful. They are not open.”

Diego Salazar, a Peruvian journalist, worked closely with many Venezuelan migrants while reporting on the influence of news media regarding immigration in Peru.

“Peru is a very conservative country in social norms,” Salazar said. “Women are expected (to be) a certain way, sexually speaking, mainly, and Venezuela is not like that at all. … They are very expressive … men and women. So that also could be a source of collision.”

Dongo also noted the tension between the two countries’ societal standards. She said that because of Venezuela’s success in international beauty pageants, Venezuelan and Peruvian women often are held to “the image of perfect beauty.”

Carmona, the recent arrival from Venezuela, said she had not seen any differences between Venezuela and Peru’s societies, but Soto mentioned multiple distinctions she has noticed in her five months of living in Lima.

Andrés León plays with his band, Costenos de Venezuela, for tips in Lima's Chinatown. A Venezuelan flag patch adorns his cap. (Photo by Miranda Cyr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Soto said people are friendlier and more respectful in Venezuela, which is seen in the way workers treat customers. Soto’s close friend, Alexa Sarahi Uzcategui Cardona, 22, said that shows the differing cultures of communication and appreciation.

“If I bought this, whoever sold it to me … should thank me,” Uzcategui said. “Why? He gave me a service, and I should thank him. ‘Thank you for your purchase.'”

Oddly, language is one of the main factors that clearly sets the two groups apart. The differing accents and colloquial terms make Venezuelans stand out in a group of Peruvian Spanish speakers.

A common distinction that Venezuelans run into on a regular basis is something as simple as terms for foods. Banana in Peruvian Spanish is “platano;” in Venezuelan Spanish it’s “cambur.” Small differences like this can lead to bigger conflicts, according to linguistics professor Luis Andrade of the Pontifical Catholic University.

“In the lexicon, there are many other differences that are very much conflicted (more) than the names of fruits,” Andrade said. “We have a special adjective that is quite different between Venezuela and Peru, which is arrecho. In Peru, it means sexually hot, excited, and for Venezuelans it means to be pissed off. I have heard – two times at least – stories of Venezuelans speaking here about his state of mind, when they were pissed off. There was an uncomfortable conversation with their Peruvian interlocutors.”

Cultural and societal differences between Venezuelans and Peruvians might be more than superficial, Andrade said. They could even be wired into the way they speak and interact with one another.

He said he’s observed “different patterns of politeness” between the two groups, where daily interactions could lead to minor conflicts.

Andrade said the two groups could encounter contrasting “face-work,” a term coined by sociologist Erving Goffman to describe socially acceptable gestures and intonations while conversing. If the two groups have different ideas of proper face-work, Andrade said, then conflict and resentment can arise. This is especially significant, he said, because Peru has a more complex hierarchy and way of speaking respectfully, while Venezuelans are more casual and less hierarchical.

Despite these differences, Andrade said the two versions of Spanish could be integrated, but there’s no way to predict when or how that might occur.

“We Peruvians have learned that language change is unpredictable,” Andrade said. “It would be very arrogant to establish a likely pattern of change for language.”

Although there have been no tested or proven studies quite yet, Andrade said he has observed Venezuelans hiding their identity by behaving or speaking as Peruvians do.

In cases like these, it can be debated whether true cultural integration has occurred, but it’s certain that the dynamic has shifted between Venezuelans and Peruvians. What was once a quite friendly environment has turned somewhat xenophobic.

Because many Venezuelans who migrated to Peru expect to return, many do not intend to integrate into the culture and society, Dongo said, which leave some Peruvians feeling like their generosity hasn’t been appreciated.

But for Venezuelans who left loved ones behind, the desire to return is strong.

Soto’s main motivation for returning to Venezuela is to reunite with her 2-year-old son, Mathias. She said she didn’t like to talk about him or her family much because it makes her cry.

“My mom called me, tells me my son is sick, cannot breathe,” Soto said. “I do not know what to do. … You know that your son is six days away (traveling by bus) and that he is sick, that he cannot breathe and that medicines are not available and that there is no money. … For me it is a very hard period.”

Soto and her friend, Uzcategui, agreed that, although they wanted to keep in contact with their families, it is hard to see them on video calls but not be able to hug them or talk to them in person. Uzcategui reminisced about homemade arepas and the feeling of being around family but said that the journey to help her family by working in Peru has made her strong.

“In migration, you win and you lose,” Uzcategui said. “You gain life experiences because I believe that someone who can emigrate can do anything in the world.”

Alexa Sarahi Uzcategui Cardona and Sara Marianys Soto Duque beam as they hold a picture of them together from 2012. They say they're more like sisters than just friends. (Photo by Miranda Cyr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

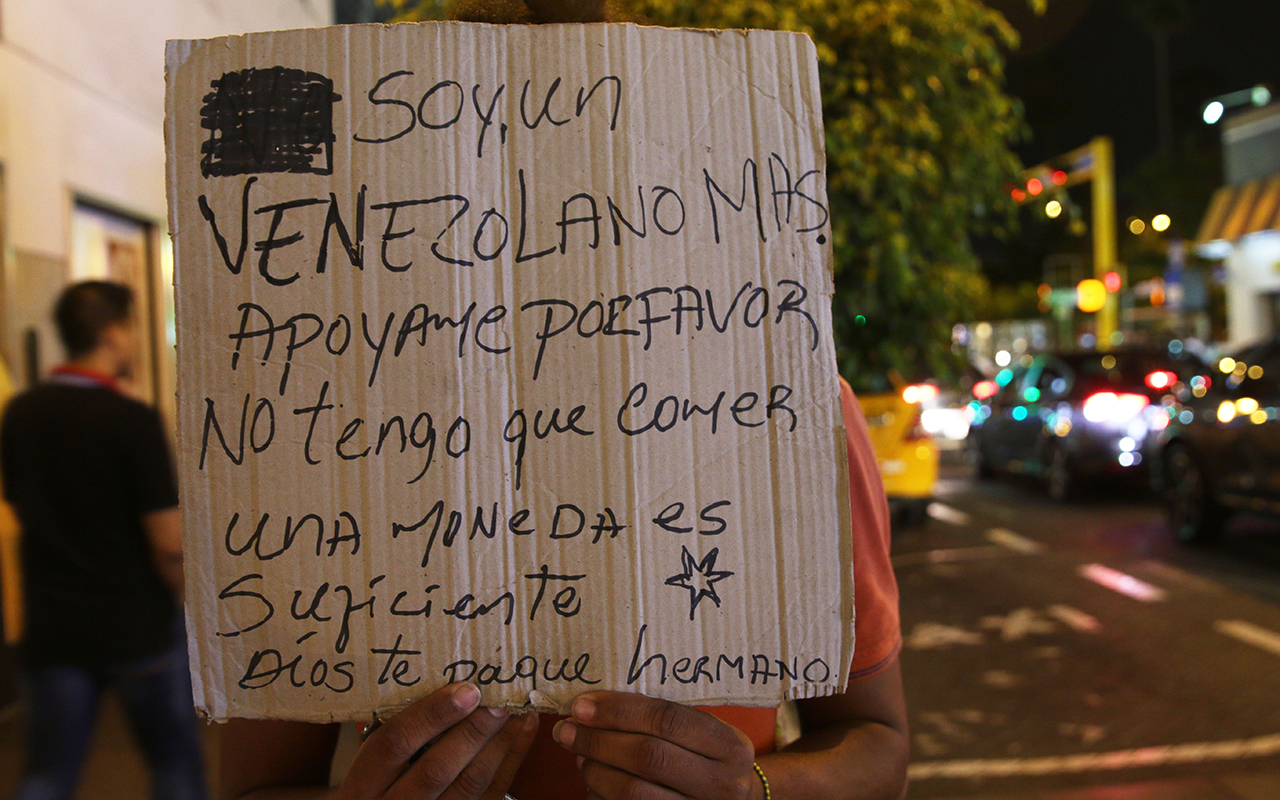

Carmona and her family traveled for two months, with little to eat, to arrive in Lima. They are staying in a hostel that opened its doors to migrants for free for up to 30 days before they need to move on.

She said she plans to find work, so she and her boyfriend can make enough for her family to live. After just a short time in Peru, it was too early to tell whether she would be open to becoming acculturated to her new country of residence.

Yenife Alexandra Carmona Rieracda with two of her children. She plans to find work while staying in the hostel so they can sustain themselves in Lima. (Photo by Miranda Cyr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Dongo said whether new immigrants decide to try to assimilate could affect how they’re perceived and accepted long-term in Peruvian society.

“Two situations can happen. They can go back (to Venezuela) when the situation is better, of course,” Dongo said. “I think that would be perfect. So the family reunites and they can go back to their lives. It could be one choice. Another one it could be is they accept they are not in Peru temporarily, so they are more willing to accept the culture and feel like they are part of Peru. ‘I’ve decided to stay here, and I’m going to do my best to embrace the culture and share their culture and values,’ but in a harmonic way.”

Soto already has made a choice. Weeks after arriving in Lima, she moved to Ecuador, where her boyfriend has family, and reunited with Mathias. But even in this new country her goals haven’t changed. She plans to find work and eventually hopes to return to Venezuela.

AlertMe

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]