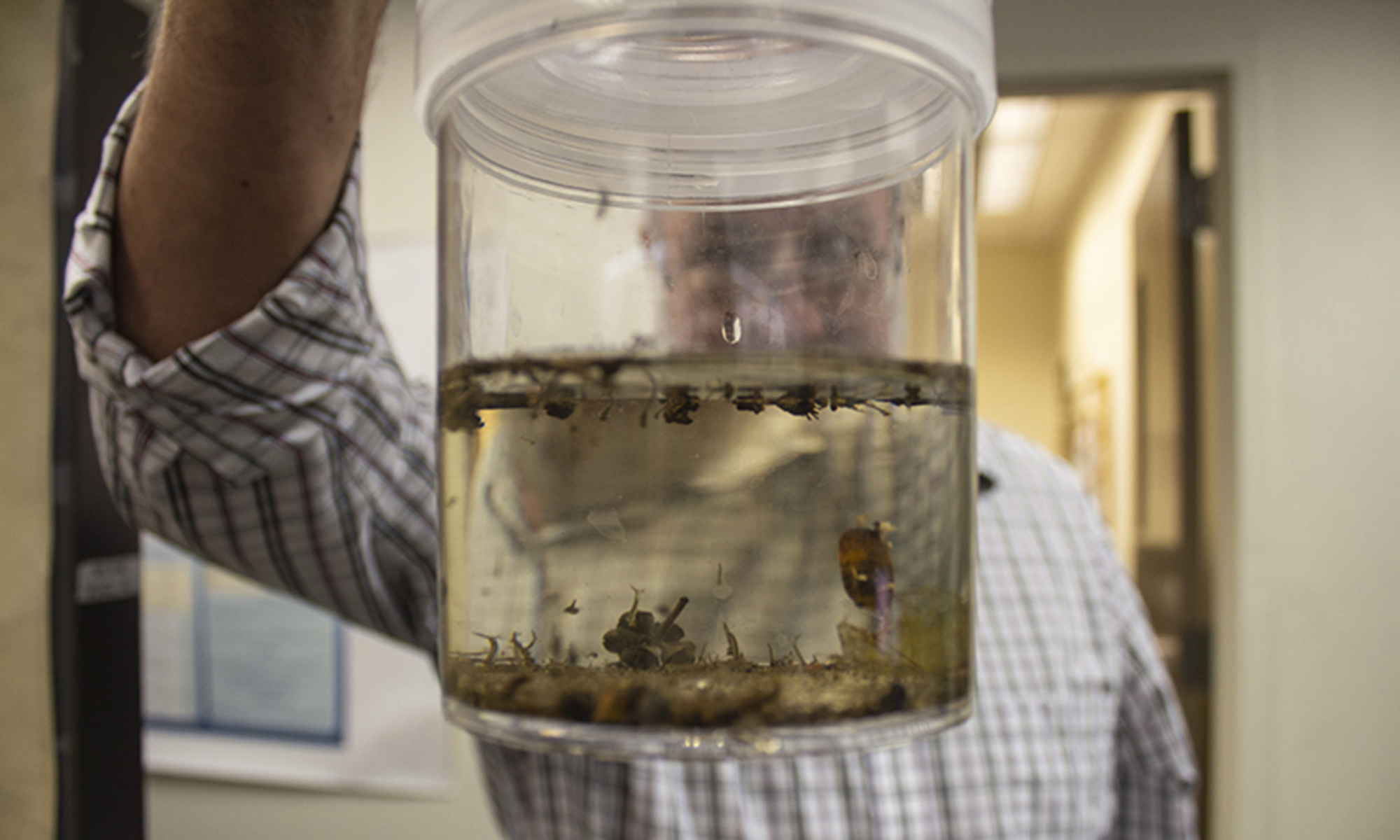

John Townsend, division manager of Maricopa County Vector Control, examines mosquitoes to determine if they carry the West Nile Virus, the most common mosquito-borne illness in Arizona. (Photo by Sarah Donahue/Cronkite News)

West Nile virus now is a permanent part of Arizona’s ecosystem, study finds

By Lauren Schieler/ Cronkite News |

PHOENIX – Every day is a challenge for Bruce Gran, 52, who was diagnosed with West Nile virus seven years ago.

“From Day 1, it’s been a migraine-caliber headache,” the Tucson resident said. “My short term-memory is terrible. I’m not old enough to be having the effects that I have. ”

Gran is one of the hundreds of Arizonans who have been infected by West Nile since the mosquito-borne disease was discovered in the state in 2003.

Sixteen years later, the virus is here to stay, according to a study from Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Phoenix. And the southern half of Arizona appears to be an ongoing source of West Nile in neighboring states.

There are several types of mosquitoes in Arizona, but the two main ones that carry West Nile – Culex tarsalis and Culex quinquefasciatus – stay year-round due to central Arizona’s mild winters, TGEN associate professor David Engelthaler said.

“We could actually find the remnants of the original strain that affected the U.S. in New York and has marched its way across the U.S.,” he said. “There’s another evolving strain that has been evolving in Texas and is now a permanent resident in Maricopa County as well.”

West Nile symptoms can vary, making the illness difficult for doctors to diagnose. Most cases cause mild flu-like symptoms; others end in death.

Some patients, like Gran, can experience a life-changing neuroinvasive illness.

“The harder you push to do things, the harder it (the virus) pushes back,” he said.

The disease has robbed the auto technician of feeling in three of his fingers, so he tapes his hands every day.

“I can’t feel anything,” Gran said. “They’re numb. But yet, when I bend my joints past a certain point, it feels like someone is driving a spike through them.”

West Nile also is the reason for Gran’s severe headaches.

“It’s a seven or an eight on the pain scale” of 10, Gran said. “It gets worse, but it never goes below that.”

After the diagnosis, he began to experience short-term memory loss.

“I can watch a sitcom tonight and watch it again tomorrow or a couple days later and not know I watched it,” Gran said.

His wife, Christine Gran, said the disease has drastically impacted their family.

“Ask my children, my three sons,” she said. “They really don’t have their dad. It’s just that debilitating.”

Many West Nile patients experience symptoms so severe they’re unable to work, but even for those who can, daily tasks can be agonizing.

“There were days for years where he would go to work for a couple hours and just be done, ” Christine said. “He only makes it until about 2 in the afternoon and then everything gets excruciating. His whole body aches and he just needs to come home and sit. We’ve lost so many days of work.”

For the days that Gran can work on cars, he needs a list to remember what jobs need to be completed.

Asked how the disease has impacted his social life, Gran responded “What social life?”

The business of mosquito trapping

After the first West Nile virus case appeared in Arizona in 2003, Maricopa County expanded its vector-control program to study and control the mosquito population in metro Phoenix. Since the following year, the number of cases in Arizona has steadily declined, to 27 in 2018.

County field inspector Dan Armijo helps place mosquito traps all over Phoenix. Vector Control sets out more than 800 traps daily.

On a recent afternoon, Armijo pulled up to a small park in a west-side neighborhood, hopped out of his truck and filled a trap with dry ice from a cooler in the back.

Dry ice is used because it evaporates to release a cloud of carbon dioxide – something mosquitoes are attracted to, Armijo said. It’s the females that bite people and other mammals to draw blood to incubate their eggs.

Armijo said mosquitoes are drawn to Arizona because, despite the dry climate, the state actually has a lot of stagnant water – puddles, water fountains, neglected swimming pools.

Armijo hung the trap on a tree branch near a fountain in the park.

“We’ll set this trap overnight,” he said. “We’ll come back and pick it up in the morning.”

The traps are individually barcoded and numbered so the inspectors can keep track of what they find. The number of mosquitoes the traps catch varies depending on weather conditions and the amount of stagnant water nearby. The captured mosquitoes are separated by gender because only the females bite and carry West Nile, Armijo said.

“If even one mosquito comes back with a trace of the virus strand, we’ll fog the whole square mile,” Armijo said.

Steve Young, a vector technologist at Maricopa County Vector Control, examines mosquitoes to determine whether they carry the West Nile virus. Two kinds of Culex mosquitos are the most common carries of the disease in Arizona. (Photo by Sarah Donahue/Cronkite News)

Here to stay

Engelthaler said the West Nile study was heavily focused on Maricopa County because the virus is mostly found in the southern half of the state.

Because the disease is a permanent resident of Arizona’s ecosystem, the strains could affect adjacent states, Engelthaler said.

“The strands that show up in Yuma and Southern California seem to be either annually or regularly coming out of Maricopa County,” he said. “Maricopa County is kind of acting as a source for neighboring areas to get West Nile virus on a regular basis.”

Engelthaler believes the study results can help Maricopa County control the spread of West Nile and raise awareness about the virus.

“We do think that this information is going to give more precise and targeted control efforts,” Engelthaler said.

Maricopa residents can file a vector complaint online. The county will send inspectors to the area to set up traps.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Have a story idea? Email us at cronkitenews@asu.edu.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]