Leaving tracks: Adrenaline-fueled count shows scant growth in Mexican gray wolf population

By Jenna Miller / Cronkite News |

ALPINE – Ole Alcumbrac has just eight minutes.

A wolf sprints across a field of dry grass, a helicopter clattering above. About 30 feet above ground, Alcumbrac – eyes glued to the wolf – leans out of an open door, into the turbulence, raises his dart gun and aims for its rump.

The chase is adrenaline-fueled, but there’s a rhythm. If Alcumbrac, a project veterinarian for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, fails to dart the wolf in eight minutes, he must allow it to rest for at least five minutes before trying one more time. And if he doesn’t hit his target on the second attempt, the wolf is free to go – until another day.

On this trip in late January, Alcumbrac’s aim is true; the wolf slows to a crawl, then stops.

“It’s a challenge, plain and simple,” Alcumbrac said.

The chase was part of the federal agency’s annual program to monitor endangered Mexican gray wolves living in the wilds of eastern Arizona and western New Mexico. The service tries to get an accurate count of the wolves, which have been listed as endangered since 1976.

The Mexican gray wolf once was prevalent in parts of the Southwest, but intensive trapping and hunting had nearly wiped out the wolves by the 1970s. They are the smallest, rarest and genetically most distinct subspecies of gray wolves in North America, officials said.

A program to reintroduce the wolves into the wild began 20 years ago, and the population has been growing slowly.

The field team said the information gathered in annual surveys plays an important role in that growth. They take great pains to capture and care for the wolves.

Alcumbrac stays within the eight-minute limit because he doesn’t want to cause unnecessary stress or overheat the wolf, which could injure or kill it.

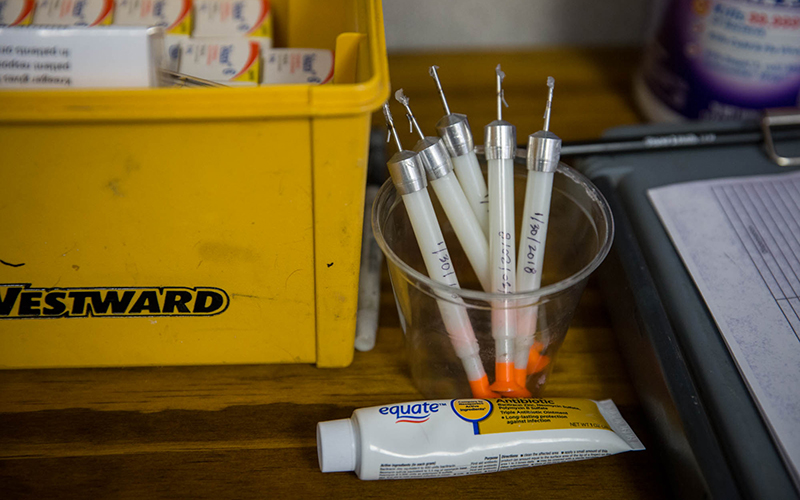

The dart, which is filled with the sedative Telazol, will knock out a wolf for only a short time. The team has to work quickly, landing the copter, racing to the wolf, and carting it back to the helicopter for a quick trip to a waiting team of biologists and veterinarians, stationed in trailers or makeshift facilities in rural locations across the wolves’ territory.

The team treats the captured wolves for any injuries, administers vaccines and fits the wolves with tracking collars before releasing them at the same spot where they were captured. The medical treatment is meant to keep the wolves healthy, and the collars help to monitor their movements throughout the year.

This year, the team captured and collared 24 Mexican gray wolves, more than any previous year.

However, after strong population growth of 16 wolves in 2016, the 2017 survey showed an increase of just one in the past year, bringing the number in Arizona and New Mexico to 114.

“It was a disappointment that we didn’t grow this year,” said Sherry Barrett, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mexican wolf recovery coordinator. “It slows our time towards recovery.”

She said officials hope for a 10 percent population growth each year, but they expect some fluctuation. They measure the growth rate as an average over a number of years to account for these disparities. The average population growth rate over the past 10 years was 7 percent.

However, a group of conservationists and environmental advocacy groups say progress isn’t being made quickly enough. They sued the federal government earlier this year in an attempt to strike down a revised Fish and Wildlife recovery plan for the Mexican gray wolf.

The original plan, approved in 1982, sought to establish wolves among three prime habitat areas: two in the Southern Rockies of Colorado, Utah and northern Arizona, and one in eastern Arizona and northern New Mexico.

Of those, officials have only reintroduced the wolf to Arizona and New Mexico habitats. They also are working with the Mexican government to monitor a population of 30 wolves in Mexico.

The revised plan, which was announced in November, calls for downlisting the Mexican gray from an endangered species to threatened species if the U.S. population reaches 320 wolves. The government would take the wolf off the list entirely if the U.S. population reaches 320 wolves and Mexico reaches 200. The plan does not call reintroducing wolves into any additional U.S. habitats in the Southern Rockies.

Conservation groups filed two lawsuits in the U.S. District Court of Arizona, and they hope to compel the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to establish a new wolf management plan.

“(The plan) is just not going to do an adequate job of recovering the Mexican gray wolf,” said Christopher Smith, wildlife advocate at WildEarth Guardians, a conservation group in Santa Fe that is a co-plaintiff in one of the suits. “It’s a massive departure from the science-based draft plan that they had initially proposed.”

Critics of the revised plan said the habitat for the second wolf population in Mexico is inferior to the available habitats in the Southern Rockies. They also say the current wolf population will struggle to thrive if the government does not expand its habitat.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan, the wolves may not roam north of Interstate 40, which runs east to west across north-central Arizona. If they find a wolf outside the boundaries, they capture and return it to its designated habitat.

“We need the data so that we can make better decisions going forward for wolf recovery,” veterinarian Susan Dicks (right) said of the testing and collaring of the wolves. “We can also make better decisions about wolf impact on humans and livestock.” (Photo by Jenna Miller/Cronkite News)

Matthew Bishop, an environmental activist and lawyer from Western Environmental Law Center, said both lawsuits are based on the 1973 Endangered Species Act, which requires the government to manage endangered species according to the “best available science.” The nonprofit, which focuses on conservation in the West, is a co-plaintiff in one suit.

“We think this (revision), at the end of the day, has to do more with political boundaries and political concerns,” Bishop said. “It violates the law.”

A Fish and Wildlife spokesman declined to comment, saying the agency can’t talk about pending litigation.

However, John Oakleaf, Fish and Wildlife Services field projects coordinator, said the revised plan reflects the gains the program has made in the past 35 years. When the original plan was written, the Mexican gray wolf program was working to build a captive population, and no animals had been released into the wild.

Oakleaf, who helped to draft the revision, said it’s more realistic and concrete than the previous plan because it establishes clear goals the federal government must achieve to end its involvement.

“That’s really our goal, to turn it over to state management and step away,” Oakleaf said. “I’ll be the happiest man when that happens.”

John Oakleaf, a field projects coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said controversy drew him to the Mexican gray wolf project. He likes to balance competing opinions and wants to prove that wolves and ranchers can live together. “It doesn’t have to be a fight,” said Oakleaf, who supervised the count near Alpine. (Photo by Jenna Miller/Cronkite News)

He said they hope the second population established in Mexico succeeds, but if the wolf can’t thrive there, the agency will consider other habitats. Although the wolf program has been controversial, Oakleaf said he believes administrators have struck an appropriate balance.

For his part, Alcumbrac tries to stay focused on the progress made to date.

“It’s just been a great deal of satisfaction and pleasure for the past 12 years seeing a population return from almost extinction,” he said.

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct inaccurate information about the number of wolves officials originally sought to establish and the number of wolves the revised plan would require for delisting or downlisting. See the full correction here.

Cronkite News reporter Meagan Barbee contributed to this article.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and Southern California PBS.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]