Part four of a four-part series

Arizona police departments try to repair rifts with communities

Kianna Gardner, Lysandra Marquez and Nkiruka Omeryone | Cronkite News

Dec. 7, 2017

PHOENIX – When Jeri Williams took over as Phoenix police chief last year, she made it a point to address the tension between law enforcement and the community.

She noted the “conflicting relationship between some people of color and some members of law enforcement” and the high-profile incidents that had resulted in unrest and violence across the country.

Arizona had seen its share of backlash, including a series of street demonstrations and city council protests – although less violent compared to other parts of the country.

“The community and the police should be one cohesive group of people who want peace and safety,” Williams wrote in a column.

Like many departments across the state, Phoenix has made efforts to repair those rifts in a variety of ways, including trying to hire more diverse officers, reaching out to youth, establishing task forces, hosting community outreach events and providing more police training.

(Video by Nkiruka Omeroyne/Cronkite News)

Arizona departments have grappled with hiring enough officers to fulfill the needs of their depleted forces. Many have emphasized the need to add more people of color and women to their ranks as they’ve tried to fill hundreds of vacant positions statewide.

While 44 percent of Arizonans are non-white, non-whites are underrepresented among officers in nearly every Arizona police department represented in a 2013 Bureau of Justice Statistics survey, according to a Cronkite News analysis of the data, the latest available.

But departments face an ongoing battle trying to overcome the “negativity around law enforcement,” Department of Public Safety Director Frank Milstead said at a news conference in April.

“Now that we need people, everybody hates us,” Phoenix Officer Lisa Fisher said at a recent recruiting event. “And nobody wants to do a job where you’re, you know, going to be spit at and kicked and hit and potentially stalked at your house and things like that. But that’s all the more reason we need good people to come out and do this.”

Repairing relationships will take time and effort, officials said.

“Law enforcement agencies across the country have truly significant problems in their communities,” said Kevin Robinson, a retired assistant chief with the Phoenix department. “I think if you dig deep, you’ll find out they didn’t bother to establish a relationship with those communities. And a lack of doing that will spell nothing but problems for you when something bad happens.”

Police departments statewide have hundreds of job vacancies, and police officials hope career fairs will spark interest from younger and more diverse generations. (Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News)

Recruitment and hiring

Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone, who voters elected in November to replace former Sheriff Joe Arpaio, said he wants to repair the broken trust between his office and the Hispanic community.

Community leaders have long accused Arpaio of targeting immigrants and promoting discriminatory policing practices.

Penzone said part of changing the department’s image involves hiring more diverse employees.

“It’s not just deputies or detention officers,” he said. “There’s a career for everyone … whether you want to work as a dispatcher or whether you want to work in some form of administration, there’s plenty of opportunity. But this organization has to reflect the community we serve.”

“We have dedicated a team solely to outreach,” he added. “And it’s not just the Latino community, it’s to all communities that are, you know, minorities or unique in some capacity.”

He said his office recently hired a human resources director who develops “everyday” methods to recruit in different areas, including at community colleges where recruiters can reach more diverse communities. Minority students in Arizona schools became the majority more than a decade ago, and those numbers continue to grow, according to research by the Arizona Minority Student Progress Report.

In the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office alone, there were more than 300 job openings in October, Milstead said then. The Sheriff’s Office has more than 700 sworn officers, a force that is about 77 percent white, 18 percent Latino, 3 percent black and less than 2 percent Native American and Asian combined, according to data provided to Cronkite News.

Recruiters for Phoenix police also have held numerous career fairs – some of them in predominantly minority areas – to attract diverse candidates.

For example, the department held an information session at a Baptist church in South Phoenix, according to an article on azcentral.com. That ZIP code has a population that’s about 71 percent Hispanic, 12 percent black and 13 percent white, according to U.S. Census information.

At a recent career fair at the Phoenix Convention Center, Isiah Brown, an African-American man, said recruitment officers had encouraged him to consider a law enforcement career.

“If you have the right type of people behind the badge with the right type of personalities, showing people the right type of respect and then also upholding the law, I think that’s really important,” he said.

The department also has put up recruitment billboards in minority neighborhoods, advertised for jobs in Spanish-language publications and spread the word on social media channels with diverse audiences.

Phoenix has nearly 3,000 sworn positions, and it’s trying to fill 400 by the end of the year. Native American, black, Latino and Asian officers account for about 26 percent of Phoenix’s sworn police force, according to data provided to Cronkite News.

Some departments even travel out-of-state to find more minority recruits. A Department of Public Safety recruiter said he had planned to travel to areas in South Carolina that have higher populations of African-Americans to seek potential recruits.

Other departments also employ more subtle ways to attract minorities. For example, the city of Maricopa made it part of its strategic recruiting plan to feature photos of women and minorities on its jobs page. The plan also includes conducting an annual review of its recruiting efforts and how it compares to the city’s demographics.

However, some experts say increasing diversity is only the first step.

“Just bringing in new people who are a different gender, different race, different ethnicity, can have some effects on how policing is done, but it isn’t going to wholesale change the nature of the business,” said Michael S. Scott, who runs the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing based out of Arizona State University.

Scott has worked at police departments in Wisconsin, Florida and New York.

“Diversity is the answer to one question. It’s not the answer to all questions,” Scott said. “What contribution does diversity have to fairer, more effective policing, to reductions in crime, reductions in disorders? It’s probably helpful, but it isn’t sufficient in and of itself.”

Recruiters also said that sometimes the quality of an applicant is more important: They hire based on the strength of the applicant, regardless of ethnic or cultural background.

Youth efforts

Millennials are now the largest living generation in the U.S., according to the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center. And as baby boomers retire from the police force, departments have increased their efforts to attract younger officers.

Because millennials are much more diverse than previous generations, department officials hope they can help shrink the racial divide. They often recruit at community colleges and sometimes high schools.

Arizona officials also have cultivated new kinds of partnerships. For example, the Franklin Police and Fire High School near downtown Phoenix opened its doors in 2007.

The school provides a pathway for teens who want to pursue careers in law enforcement or EMT/firefighting. It partners with the city’s police and fire departments for internships and training.

According to an American Community Survey estimate, from 2011 to 2015, roughly 40 percent of the youth in Arizona, ages 15 to 19, were Hispanic. At Franklin High School, the student body is composed of 90 percent Hispanic students, according to the school district.

Students can take courses such as forensics, law enforcement and firefighting and Spanish for public safety.

Nationwide, departments also have emphasized improving youth-police relations by hosting town halls put together by organizations such as Council for a Strong America.

That’s important because national studies indicate younger residents tend to have lower opinions of law enforcement. A recent nationwide Gallup survey showed confidence in police was lowest among 18 to 34-year-olds compared to other age groups.

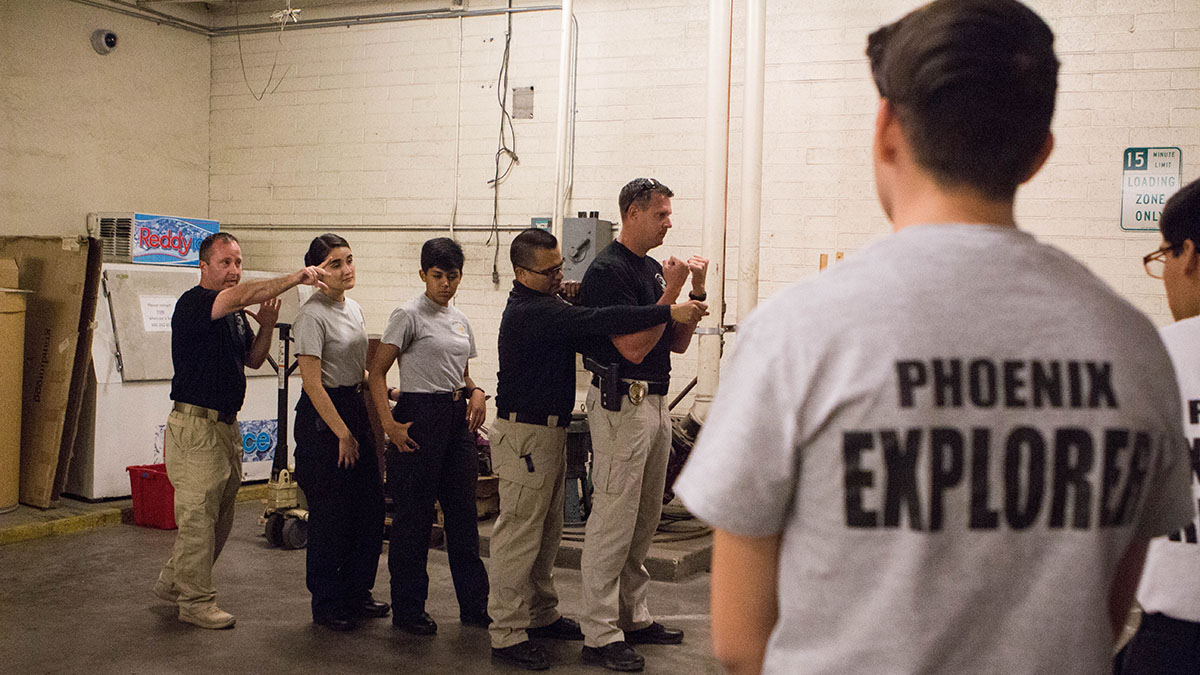

Police also offer the statewide police “Explorers” program to connect with young adults from 14 to 21 years old. The groups participate in community cleanups, first-aid training and crowd control.

Getting Arizona Involved in Neighborhoods brings law enforcement officials and locals together to strengthen police-community relations. (Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News)

Approachability

Officer Daniel McCloud, an officer and recruiter for the Phoenix Police, said his department has reached out to minority groups by attending community events such as gay pride parades and church functions.

“We’re just reaching out the communities,” McCloud said. “Instead of waiting for them to come to us, we go to where they are.”

Police also are trying to make themselves more approachable through small changes, such as riding bikes instead of driving cars.

“Let’s face it, our uniform is sometimes unapproachable to some people,” Phoenix Lt. Wayne Dillon said. “The car can be a little bit intimidating. But if we’re on a bicycle, and we’re just riding around as a group, sometimes the community members feel like they can just go up to us, and even more so kids.”

Police departments also have utilized community liaison programs, where residents who feel uneasy around police can use a mediator to contact them.

In Winslow, Chief Dan Brown stepped into his new position shortly after an officer fatally shot a Native American woman in 2016. The event led to tensions between the police force and some members of the community.

Eventually, residents stopped bringing complaints and issues to the police.

Brown eventually looked to neighboring Flagstaff, where officials launched a community liaison committee to act as a buffer between the community and the police department.

Brown decided to create a similar program in Winslow.

“It’s not an oversight committee, you know, telling us how to do our jobs. It’s a transparency thing, if you will, so they work with us,” Brown told The Tribune News.

Representatives from the Navajo Nation and NAACP will help create the committee, which Brown hopes to finalize by June 2018.

Many police departments statewide count on programs such as GAIN, Getting Arizona Involved in Neighborhoods, to connect with communities.

Dillon said GAIN came to Arizona more than 20 years ago. It’s an annual event that occurs at different times in different cities across the state, allowing communities to connect with their local law enforcement. The focus is on increasing community involvement in Neighborhood Watch programs.

For law enforcement, it means an opportunity to foster positive relationships.

“Over the last 23 years of my career, I’ve seen a huge increase in not just community involvement from a direct standpoint of calling the police and so forth, but also in our ‘community action,'” Dillon said.

Dillon said community action involves contacting local police on “quality of life” issues such as blight, graffiti and transient problems.

Another popular social engagement strategy is hosting “Coffee with a Cop” events, which allow community members to ask questions, raise concerns or clarify confusion. These events also aim to build a relationship between the officers patrolling the area and the residents they serve.

Coffee with a Cop keeps a map on its website that shows upcoming events.

Gilbert Police Officer Alexander Ramos shoots a rifle during a training course in the desert in Apache Junction. Officials say police training is key to addressing some community concerns. (Photo by Emily L. Mahoney/Cronkite News)

Training

Police training is one way to address issues such as excessive use of force or increasing awareness of other cultures.

The Rev. Jarrett Maupin, a high-profile civil rights activist, has been at the heart of many grassroots movements across the Valley. He has organized marches against police brutality and advocates for racial justice.

“There are new concepts about how you talk to and engage minority communities, especially the youth and undocumented people,” Maupin said.

Maupin said Phoenix has made progress to address certain issues, following a 12-point plan shared by the Black Lives Matter movement during a 2016 protest, according to an article in The Phoenix New Times. The protest ended when former Phoenix Police Chief Joe Yahner signed the document.

“We have a mental health review board and increased resources for people who are in a mental health crisis,” Maupin said.

The mental health review board is one of 12 boards that constitute the Phoenix police chief’s advisory board.

Phoenix City Manager Ed Zuercher also formed an initiative in 2015 that makes recommendations to help the department build trust. Some of the recommendations include conducting a community survey, adding more body cameras and providing “cultural competency” training for officers.