Part three of a four-part series

Some Arizona residents push back against police through protests, ballot box

Fortesa Latifi, Tim Johns and Chelsea Rae Ybanez | Cronkite News

Dec. 7, 2017

PHOENIX – As thousands of protesters hit the Phoenix streets in July 2016 to protest the killings of black people by police, the Rev. Jarrett Maupin felt their anger.

Maupin, who has positioned himself as one of Arizona’s most high-profile civil rights activists for the past decade, is no stranger to conflict: He’s helped organize protests across the Valley, one of which threatened to shut down Valley freeways.

But this march, he said, felt different.

“That was the first time I had ever been at the helm of a march reminding people to be non-violent, reminding people to watch their language and their level of aggression,” he said. “That was the first time I had been attacked at the front of the march by people who were marching, and it’s quite a thing to be attacked by people when you’re at the helm of the march.”

Protests have broken out across the country as videos of police killing unarmed black men have gone viral, juries have acquitted white officers in the killing of black people, and white nationalists have taken to the streets to fight for white power.

Arizona wasn’t immune to the unrest. Maupin said people here were simply “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

(Video by Chelsea Rae Ybanez and Tim Johns)

Arizona residents have pushed back against what they view as a history of discriminatory laws, police brutality and police overreach in a variety of ways – from shutting down city council meetings and staging protests to running for office.

Joseph Garcia, the director of communication and community impact at the Morrison Institute, said he’s seen progress in Arizona as voters ousted prominent elected officials – including Sheriff Joe Arpaio, Maricopa County Attorney Andrew Thomas and Arizona State Senate President Russell Pearce – all of whom supported stricter immigration policies.

Arizona to become minority-majority state

Arizona long has wrestled with racial tensions.

In the 1970s, Cesar Chavez led a hunger strike to bring attention to the plight of Arizona’s migrant farm workers. Arizona was one of the last states to adopt Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday, prompting boycotts and perceptions of the state as racist.

And when the state in 2010 passed Senate Bill 1070, which required law enforcement officers to determine the legal status of people they stop, it resulted in the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue from the protests and boycotts that followed, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

But Arizona is on the edge of a demographic tipping point. The state now has the sixth-largest Latino population in the country, according to Pew Research Center.

According to the Morrison Institute for Public Policy, based at Arizona State University, the state will become a minority-majority state within the next 10 years, meaning the non-white population will become the majority of the state’s population.

Yet the balance of power doesn’t necessarily reflect those demographic changes.

A 2016 analysis by The Arizona Republic found that 74 percent of Arizona lawmakers were white and non-Hispanic even though they only make up 56 percent of the statewide population. Only 19 percent of legislators were Latino, although they made up 30.5 percent of the state population.

The racial imbalance also is reflected in the state’s police forces. While 44 percent of Arizonans are non-white, non-whites are underrepresented among officers in nearly every Arizona police department represented in a 2013 Bureau of Justice Statistics survey, according to a Cronkite News analysis of the data, the latest available.

Police officers monitor the protest in Tempe on Sept. 26, 2016. (Photo by Kennedy Scott/Cronkite News)

Last year, an Arizona Republic/Morrison/Cronkite News poll found that a plurality of Arizonans believed police treat people differently based on their ethnicity.

Garcia said he’s surprised those numbers aren’t higher – especially after a federal judge ordered former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio to stop his officers from using racial profiling in policing and traffic stops.

“That’s not what many Arizonans accepted as good law enforcement,” Garcia said. “So that kind of tells you that, yeah, there’s a plurality, but why isn’t this unanimous? That this is unacceptable. That everyone says this is not right, you cannot treat people this way.”

Edder Diaz Martinez, 28, said his personal experiences have led him to believe police treat people differently based on ethnicity.

“I know the police are there to protect us … but unfortunately for me and a lot of people in my community, we’ve had encounters where we’ve been stopped or questioned or sometimes have had encounters where it seems like they’re being targeted specifically because of the color of their skin,” Martinez said. “Those experiences have been traumatizing.”

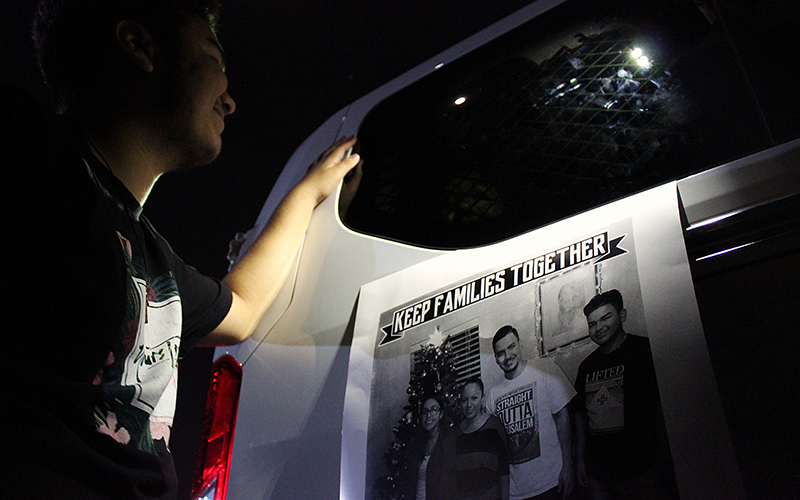

Community members protest after Guadalupe Garcia de Rayos was arrested in February at the Phoenix Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices in central Phoenix. (Photo by Josh Orcutt/Cronkite News)

People take to streets

For Maupin, protest marches provide a way for communities to express frustration without violence.

“If people didn’t march, they would riot,” he said. “If people didn’t take over a bridge, they would probably take up arms and engage in acts of violence as victims who are tired of being victimized.

“We don’t know how close we are to that in this country sometimes,” he added.

Local protests attracted hundreds – sometimes thousands – of participants:

- ● In July 2016, protesters chanted in front of Phoenix City Hall after a series of fatal shootings of black men by police across the U.S.

- ● In September 2016, protesters blocked Tempe’s Mill Avenue bridge to protest the shootings of two African-Americans, Dalvin Hollins in July by Tempe police and Michelle Cusseaux in 2014 by a Phoenix sergeant.

- ● In February, protesters surrounded an Immigration and Customs Enforcement van after Guadalupe García de Rayos was deported following her yearly check-in at ICE.

- ● In August, thousands of protesters lined the streets of downtown Phoenix to speak out against President Donald Trump’s appearance in Arizona.

“When people feel they are discriminated against in a systematic fashion, doing any sort of activism, even if it requires risk, almost always benefits in mental health outcomes,” said Eric Swank, a professor of social and cultural analysis at Arizona State University. “So they feel better about themselves, and they feel better about members of their community.”

Angel Rayos talks to his mother, Guadalupe Garcia De Rayos, who being taken away by ICE officers. (Photo by Charlene Santiago/Cronkite News)

Chimene Hawes attends a protest at Phoenix City Council to voice concerns about police. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo/Cronkite News)

Devin Franklin and Sarah Coleman at a September 2016 march in Tempe to protest the death of her first son, Dalvin Hollins. (Photo by Kennedy Scott/Cronkite News)

Residents hold up Black Lives Matter signs at a community meeting in Phoenix. (Photo by Isabel Menzel/Cronkite News)

Residents take political action

Redeem Robinson, a member of Black Lives Matter, said he decided to run for Arizona State Senate because he wants to change the system from within.

He said he has feared police since he was a child. When he rode in the backseat of his mother’s car and a police car passed, he said she would panic and “tell me not to look at the officer.”

“In the black community, we have to have a conversation on how to interact with police,” the 28-year-old Tucson native said. “Don’t do this. Don’t say that. Keep your hands where they can see them because you can get shot. You can get arrested. They can do this.”

He said he wanted to take “concrete action” because issues of social injustice affect so many people.

“I literally cannot just stay at home watching injustice going on, watching all these things go on and just march,” he said. “That’s not really going to solve much, so I have to be a solution. I have to be part of the solution.”

Robinson’s website includes a “platform” page, but it doesn’t provide specific details on how he would address policing issues other than to say he would fight “against barriers” that prevent success.

Garcia, of the Morrison Institute, said voting is another way for residents to push back.

“We saw the pushback in the election,” Garcia said. “We saw Sheriff Joe Arpaio, despite having all those millions of dollars, go down in flames in defeat.”

The November election was a stunning defeat for the Republican sheriff who had served in the post for more than two decades and attracted local and national popularity – and notoriety – for years.

Although Latino activists celebrated Arpaio’s ousting, Maupin said residents still need to get to the polls.

“We have to get over voter apathy,” Maupin said. “We have to vote. We have to engage. We have to be involved in the process. A lot of young people tell me this, ‘I don’t vote because it doesn’t matter. Why should I vote on the city council election?'”

“Well, they hire the chief and the city manager and the city attorney,” he said. “You know, the county attorney decided whether or not to charge the officers who’ve killed somebody.”

Kenneth Perkins, a Phoenix resident, said he’s a “concerned father” who doesn’t want his kids to grow up in a “racist world.” (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

Has Arizona ‘learned its lesson?”

Garcia said the political landscape in Arizona has changed, and there’s no room now for “aggressive treatment toward ethnic minorities.” He said the business community won’t stand for it.

“The truth is brown is the new green when it comes to money and the economy in Arizona,” he said.

“Arizona has learned its lessons on what is too far and perhaps us learning those lessons will prevent us from going to that further extreme that results in, in my opinion, senseless violence,” he added.

Garcia said the public might see occasional “flare ups” and problems with police issues here. But the state hasn’t had to deal with the same kind of rage felt in other places in the country.

“We’ve been fortunate that we haven’t had some of those very national … egregious cases of seemingly police brutality caught on video we’ve all seen on the nightly news,” he said. “There is a different dynamic that takes place especially in Midwest and East (where) you’re mostly dealing with the whole Black Lives Matter movement and often white police officers shooting male black suspects.”

Maupin, however, has a different take on the level of unrest in the state.

“There is potential for there to be a lot of rage because of the broken promises locally,” Maupin said. “We saw that around the country with the Molotov cocktails and the fires and the burning of buildings. … We came very close to seeing that here in this city.”

He said the community wants good leadership and when that doesn’t happen, “sometimes that means raising hell, holding them accountable, holding their feet to the fire.”

Swank said any large American city could face violent protests: “If people feel that their voices are not heard, and they don’t have legitimate channels to deal with police reform, I think every single large city in the United States could potentially have riots.”