Moon & Sun

Native American parable explains centuries-old trauma

McKenna Leavens, Allison Vaughn, Anne Mickey, Rylee Kirk, Brendon Derr and Leilani FitzpatrickHoward Center for Investigative Journalism

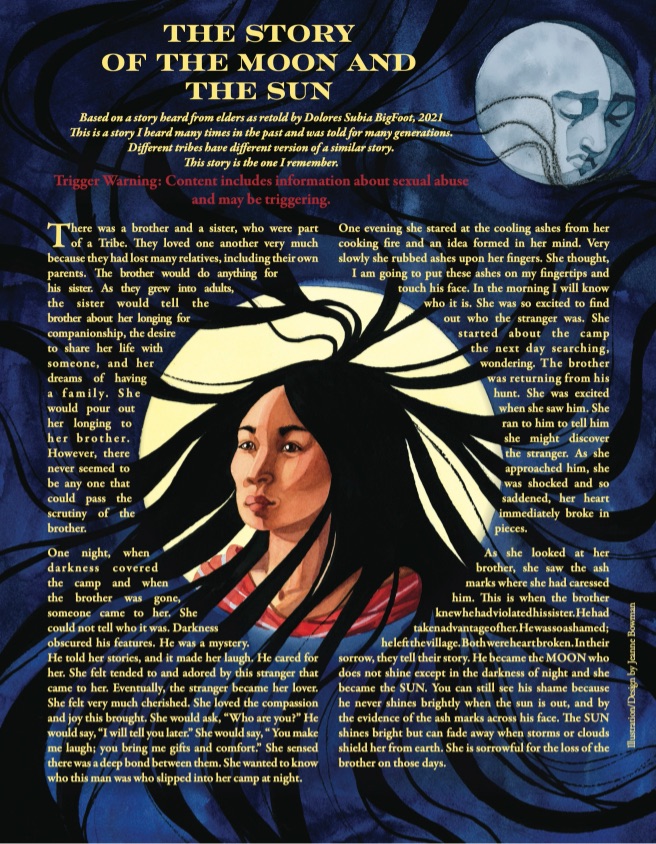

Child sexual abuse is such an age-old problem that it’s explained in many Native American communities with a parable known as the Story of the Moon and the Sun.

As retold by child psychologist Dolores Subia BigFoot, a member of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, the story is about a brother and sister who have lost their parents and many relatives and have only each other.

The sister longs for companionship and tells her brother of her “desire to share her life with someone,” the parable goes.

One night, a man comes to her in the darkness of their camp. She cannot tell who he is, but he’s kind and makes her laugh and, over time, they become lovers. Ultimately, the girl learns that the stranger is her brother, and they are devastated.

“He became the MOON who does not shine except in the darkness of night and she became the SUN. You can still see his shame because he never shines brightly when the sun is out,” the parable says.

BigFoot directs the Native American Programs at the Center on Child Abuse and Neglect at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. She says some version of this parable has been shared among different tribes for generations.

Barbara Bettelyoun is a citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community of Minnesota with doctorates in child development and child clinical psychology. She runs Buffalo Star People, a South Dakota-based organization specializing in healing historical and childhood traumas in Native communities. She and her husband, Francis, speak nationally on child sexual abuse in Native American communities.

“I don’t think that there’s an Indigenous family who has not been touched by this,” Bettelyoun said, pausing. “I don’t think there’s one; I don’t know of one.”

Rape has historically been used as a weapon of war, and that was true when settlers colonized Native American lands. According to Bettelyoun and other experts, this learned abuse has been passed down through generations, creating intergenerational trauma.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Native cabinet member in U.S. history, noted the “long-standing intergenerational trauma” and its “cycles of violence and abuse” when she announced in June a federal investigation into the legacy of Indian boarding schools.

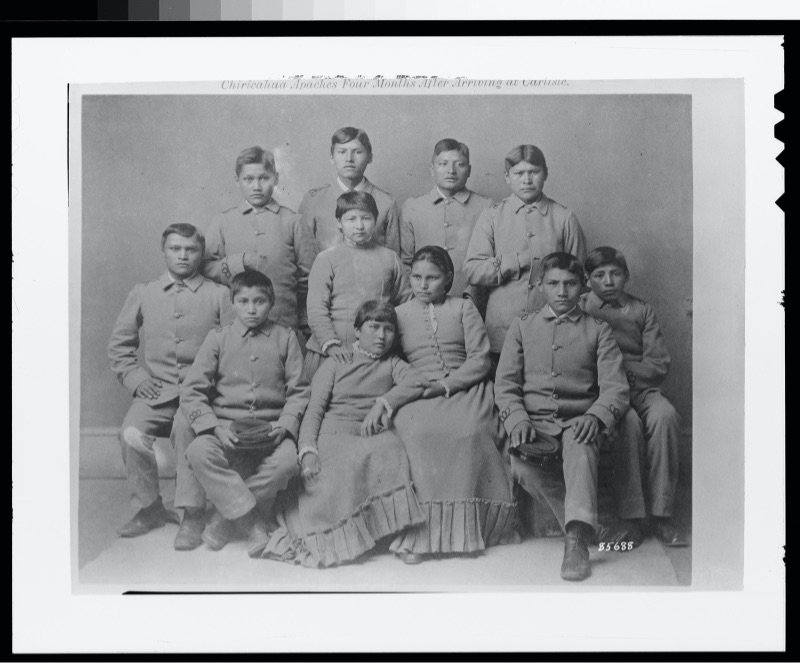

Christian churches and the U.S. government established the schools in the 19th century to forcibly assimilate Native children into American culture. The children were taken from their families and sent — sometimes thousands of miles away — to boarding schools, where their long hair was cut short and they weren’t allowed to speak their own languages, wear traditional clothing or practice their religions.

“The intent was so that when the children came back to their own families and villages, they would be ashamed of being Indigenous,” Bettelyoun said. “They did that by raping our children and molesting our children and abusing them in horrific ways.”

The remains of hundreds of children have already been found on the former grounds of Canada’s largest Indigenous boarding school.

A 2012 study by researchers from the University of Washington found that “former boarding school attendees reported higher rates of current illicit drug use and living with alcohol use disorder, and were significantly more likely to have attempted suicide and experienced suicidal thoughts in their lifetime compared to non-attendees.” The survey of 447 American Indian, Alaska Native and First Nations adults from urban areas who self-identified as LGBT, Two-Spirit or having engaged in same-sex behavior also found that those who were raised by someone who attended boarding schools were more likely to have attempted suicide and experienced suicidal thoughts in their lifetime.

Dr. Renée Ornelas, a child abuse pediatric specialist for 30 years who works at Tséhootsooí Medical Center in Fort Defiance, Arizona, said the Native children sent to boarding schools were physically, sexually and spiritually abused. And the cycle of violence continued when these children, who were never parented, returned home and became parents themselves.

“All these things that you learn as you’re growing up about how to be safe, nobody ever taught them,” Ornelas said, adding that nine of 10 caregivers who bring their child to her clinic for sexual abuse have been abused themselves.

In addition, she said, the modern-day version of boarding schools are now seeing cases of children abusing other children. “What we know now is that if you’re growing up in a home where there’s domestic violence, you can learn sexual abuse. You can do that to other children, not for sexual gratification, but to cause humiliation, embarrassment, bullying.”

The trauma of childhood sexual abuse doesn’t just create lifelong emotional turmoil, it can lead to long-term physical problems, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, said Debra Kaysen, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University.

Speaking of boarding school survivors, Kaysen said, “What you get is somebody who is highly traumatized, who’s sent back to a community, often without coping strategies for how to manage their distress.”

Francis Bettelyoun, a member of the Oglala Lakȟóta and Yankton Sioux Tribe, is an Indigenous liaison to Winona State University in Minnesota. He is descended from boarding school survivors and says he was sexually abused as a child.

“I deal with this every day. I can’t not separate myself from the trauma that happened. My dad was in boarding school, his dad, my grandfather as well, and the two generations before dealt with this, as well,” Francis Bettelyoun said. “To get through this, it needs to be recognized that this isn’t something that goes away and will go away through time. This is something that needs to be addressed by those who have done it and those that are part of it now.”