Chapter 2

The federal trust: ‘no justice, just unfairness’

Every day that Christine Benally looks out of the window of her home, she’s reminded of how the federal government failed to protect her child. Some 200 yards away sits the house of the man she says sexually assaulted her son.

In November 2005, Benally’s then-13-year-old son told her that he had been sexually abused by a relative over several years. What happened next, based on records Benally provided to the Howard Center, was a by-the-book approach to seeking help.

Benally filed a crime report with the Navajo Nation Police Department in Shiprock, New Mexico, and also contacted social services. When she and her son met with police, they provided the names of those involved, including the suspect, the time frame of the incidents and location of the alleged crimes. According to Navajo police records, the suspect “confessed to the allegations.”

In January 2006, Benally was interviewed by a Navajo police criminal investigator and, records show, both she and her son were later questioned at their home by FBI agents from nearby Farmington, New Mexico. Records from Navajo family court also say that one of the FBI agents said the suspect had confessed.

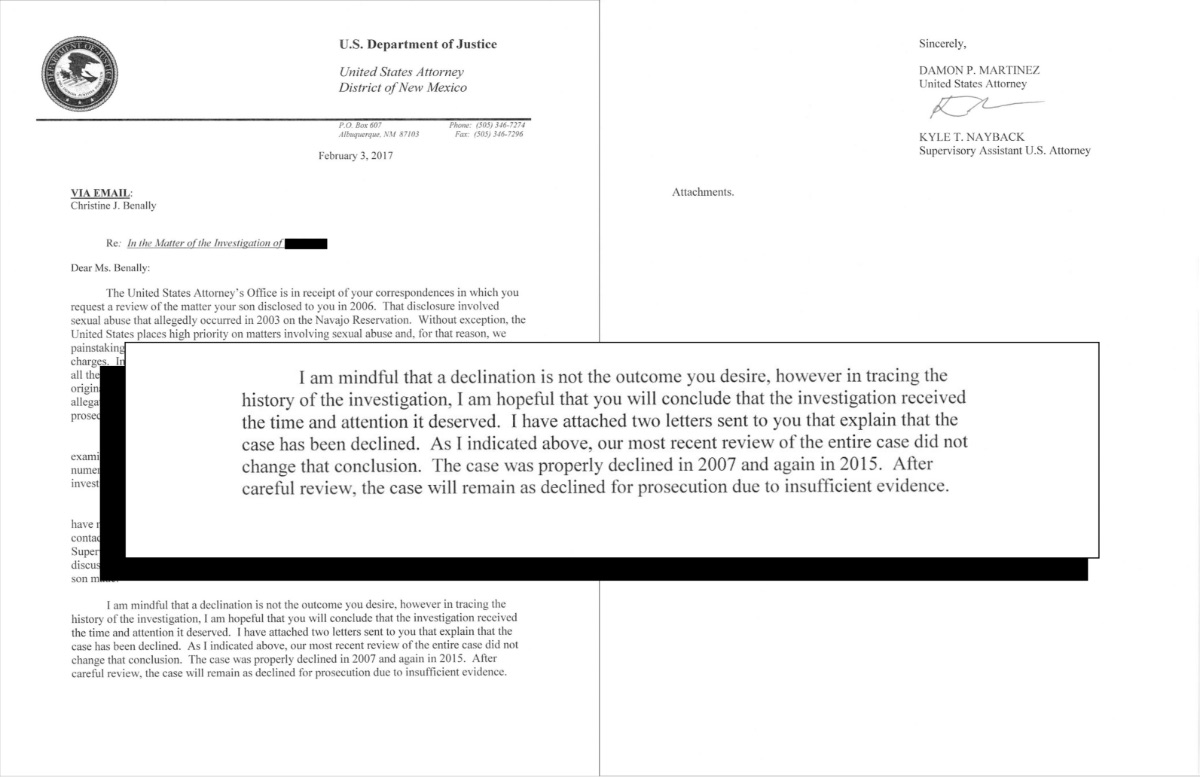

But in November 2007, two years after first contacting police, Benally received a fax from an FBI victim specialist in Farmington, saying that an assistant U.S. attorney had declined the case. No reason was given.

Benally is well-known in her community, in part because she refused to drop the issue and move on quietly with her life. After the suspect moved back to the family homestead in 2012, she began lobbying for the U.S. Attorney’s office to reopen her son’s case. She even appealed to then-President Barack Obama.

In 2015 and 2017, she received three more letters from the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s office in New Mexico, restating that the case was closed for insufficient evidence, but offering no details.

Benally says she still doesn’t understand why the case was declined.

Amber Kanazbah Crotty, a Navajo government official who accompanied Benally to a meeting with federal prosecutors in 2015, said she didn’t know either. “I do not have the clear answers on why there was a federal declination. When we spoke with the U.S. attorney’s office with Christine, they had just told her in my presence that they had already told her … the reasons why her case was declined.”

The Justice Department’s handling of major crimes in Indian Country has long been a concern.

In December 2010, the Government Accountability Office — the investigative arm of Congress — issued its findings on how often federal prosecutors were declining to prosecute cases from Indian Country, where violent crimes were running about 2.5 times the U.S. average.

From 2005 to 2009, investigators found, U.S. attorneys declined to prosecute about half of all violent crimes and 67 percent of “sexual abuse crimes and related matters.” The report did not distinguish between adult and child sex abuse crimes. Reasons for declinations varied, but weak or insufficient evidence was most frequently cited.

Earlier that year, Congress had passed the Tribal Law and Order Act, aimed at addressing these high rates of violent crime. It expanded data collection from the FBI and U.S. attorneys about cases referred and declined for prosecution and required that information be made public annually. Those reports show consistently high levels of FBI case closures and Justice Department declinations for child sexual abuse crimes.

For tribal courts that met certain judicial standards, the act increased sentencing authority from one to three years and fines from $5,000 to $15,000. And it formalized the role of tribal liaisons — assistant U.S. attorneys whose job was to build relationships with tribal authorities and develop multidisciplinary teams of federal and tribal prosecutors, investigators, victim witness coordinators and others to investigate crimes such as the sexual abuse of children.

By 2017, the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General had found widespread problems with the law’s implementation.

“We found that no Department-level entity oversees Indian country law enforcement activities or ensures the Department’s compliance” with the act’s mandates, the inspector general’s report said.

There was no “coordinated approach to overseeing the assistance” provided, the report said. The department had not prioritized assistance “consistent with its public statements or annual reports to Congress.” It also needed to do more to ensure all required training was being provided. Crime data in Indian Country “remains unreliable and incomplete,” the report found. And despite Indian Country being a “priority area,” funding for federal prosecutions there had decreased by 28% from $27.6 million in 2010 to $19.8 million in 2016.

The inspector general also noted that the tribal liaisons — those assistant U.S. attorneys who were supposed to improve relations between tribal and federal authorities — were nearly ineffective because they continued to carry full caseloads, leaving little time for tribal liaising.

The lack of oversight and coordination meant that U.S. attorney’s offices around the country differed in how they prioritized and implemented Indian Country obligations. More than half of the operational plans of U.S. attorney’s offices with Indian Country jurisdiction lacked basic protocols for things like notifying tribes about case declinations, the report said, with some tribes never receiving notice.

That’s apparently what happened in Benally’s case.

When she asked tribal prosecutors in 2014 to consider taking her son’s case to Navajo court, they twice wrote to the FBI’s special agent in charge in New Mexico asking for information on why the case was declined.

Ultimately, it didn’t matter. In April 2016, the Attorney General of the Navajo Nation wrote Benally acknowledging concerns “about the sexual assault perpetrated against your son that you reported several years ago,” but noting that the statute of limitations had expired for prosecution in Navajo court. There is no statute of limitations in federal court for child sexual abuse.

Where ‘truth comes to die’

FBI agents are often the federal government’s first representative on the scene of a reported crime in Indian Country, even though they may live and work hundreds of miles away. In Colorado, for example, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe are between a 320- and 400-mile drive from the Denver offices of the FBI and U.S. attorney. Given that the FBI has no 911-like intake process, agents are always one degree removed from any Indian Country investigation.

The Justice Department’s inspector general also noted that FBI agents received inadequate training, despite the unique cultural, jurisdictional and geographic challenges of working in Indian Country. High-turnover rates among agents working in Indian Country, considered a hardship post under agency guidelines, make it difficult to build relationships with tribal authorities, which ultimately affects the quality of investigations.

Timothy Purdon, the former U.S. attorney for North Dakota, said there was sometimes a “lack of quality investigations” so that when an abuse case reached the federal prosecutor’s desk there was insufficient evidence for a conviction. He said he often encouraged his FBI partners to allocate more resources for investigating child sexual abuse in Indian Country: “You’re constantly fighting with the Bureau to get them to prioritize these cases.”

The former FBI agent in Indian Country, who asked not to be named so that he could speak freely, said the decision to decline a child sex abuse case had a lot to do with a prosecutor’s “comfort level” and that U.S. attorneys were more accustomed to cases that are “cut and dried.”

He also said there was virtually no oversight, beyond front-line supervisors, of FBI agents’ decisions to close cases, and senior management “never ever look at (closed) cases due to insufficient evidence in Indian Country.”

Wyn Hornbuckle, the Justice Department spokesman, highlighted seven cases over the last six years of “significant prosecution” of child sex abuse in Indian Country, leading to convictions, ranging from life to less than two years.

But even when such cases seemingly have everything needed for conviction, they can still fall apart.

In September 2013, Leo Thompson, a member of the Navajo Nation, pleaded guilty to sexually abusing his girlfriend’s granddaughter when she was 12. But before his sentencing hearing, the victim sent two letters to the court recanting her accusation. From there the case collapsed — charges were dropped, and Thompson went free.

According to an official transcript of the dismissal hearing, the prosecutor told the federal court in New Mexico he believed that family pressure played a role in the girl’s decision to recant. “Sometimes, sadly, the courtroom is a place where the truth comes to die, and that’s what happened in this case,” prosecutor Jack E. Burkhead said.

Unsuccessful with prosecutors, Christine Benally sought other legal measures to help her son. He filed for a protective order against his alleged abuser in Navajo family court in 2014. It was initially denied, but in 2017 the Navajo Supreme Court granted temporary protection. The high court ruled that Benally’s son “did prove by a preponderance of the evidence that it is more likely than not” that the abuse had occurred, even though the alleged abuser now denied it.

News of that decision came in a letter from the court addressed to her son, who was by then away at college. “What do they want with him now?” Benally recalled thinking.

The letter sat on her kitchen counter for a week before she mustered the courage to tell her son about it over the phone.

“He was crying, and he says, ‘So they believe me?’” she said.

For Benally, the acknowledgement 12 years after their first report to police, was too little, too late.

“There’s no justice,” Benally said. “There’s just a lot of unfairness.”

Previous Chapter

Previous Chapter